When the death of Russian lawyer and opposition leader Alexei Navalny in a remote Siberian penal colony was announced to the world on February 16, 2024, Shane Boris ’00 was in California. It was well before dawn on a West Coast Friday morning. The temperature would be in the mid-60s by noon; his phone was already blowing up.

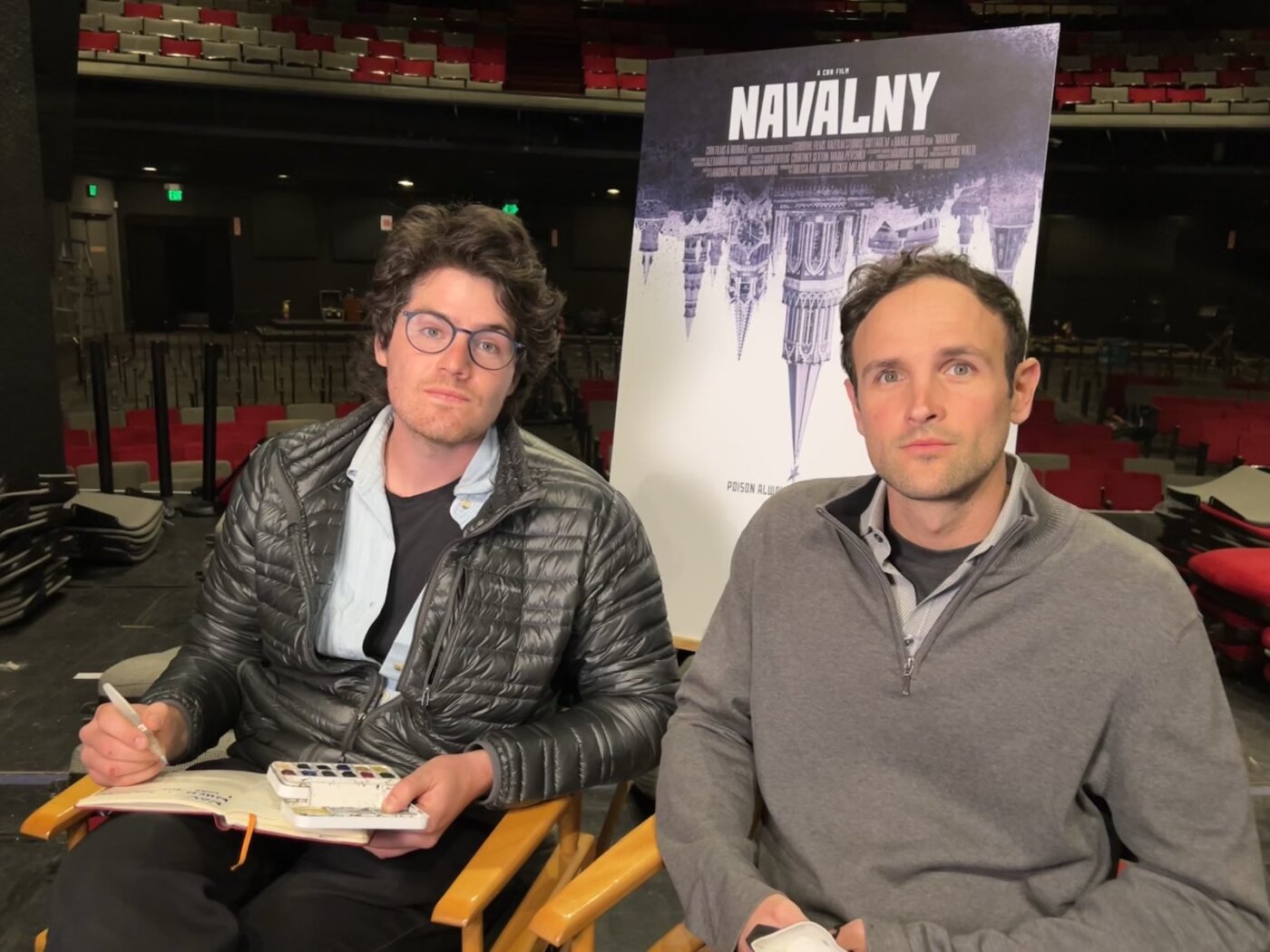

A film producer who was part of the five-person team that won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature at the 2023 Academy Awards ceremony with Navalny—which revealed previously unknown details about the Kremlin-orchestrated plot to poison the outspoken critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2020—Boris awoke to hundreds of texts informing him of a brave man’s passing.

With just a few minutes to process the news, he rushed across Los Angeles to join the film’s director, Daniel Roher, and fellow producer Diane Becker. They mourned quietly in disbelief for an hour or so, spoke briefly with producers Melanie Miller and Odessa Rae as well as other colleagues and supporters of the film about the news, and then steeled themselves to face a barrage of inquiries from the world’s press that lasted several weeks.

It’s not often that one is anointed as a voice of authority regarding an event of world-historical significance, but that is the role in which Boris and his colleagues found themselves.

“We always knew this was a possibility—we expected it,” Boris told reporters alongside his team, “and never imagined it could happen.”

At the time, the award-winning producer—who received a second Oscar nomination in 2023 for Fire of Love, chronicling the work of French volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft—didn’t use the word “murder” to describe Navalny’s death, which occurred in what is regarded as one of the harshest prisons in the world. Navalny had recently been transferred there from another, slightly less feared maximum-security facility, where he spent months in solitary confinement.

But today, Boris states, “It’s clear that Putin is responsible. We may never find out whether it was a direct order, but we do know that it was Putin labeling Alexei as an extremist that sentenced him to 20-plus years of imprisonment in the worst conditions imaginable.”

An enduring message

Still, Navalny’s message lives on, according to Boris. “The world we hope to bring into being can only exist if we act and we stand up for what we believe in. We cannot allow authoritarianism to go unchecked. The sacrifices Alexei made are testaments of great bravery, and can inspire us to act in whatever way we can to stand against authoritarians in our own country or wherever they rear their heads.”

“One of the things that Alexei spoke most about in his work,” Boris continues, “was the need for each individual to do what they are able to do, to give what they can give. I think about that a lot: that we all have gifts to give to this world, and then there are things that this world needs. Our journey is to figure out how those two meet.”

Navalny, explains Boris, understood that his duty was to Russia and to freeing it from the authoritarian grip of Vladimir Putin. “And he did everything he could—including giving his life—for that cause.” Not everyone can or should give the same. “We each need to ask ourselves, ‘What do we have to give?’”

Boris recalls that at Colorado Academy, the critical model of challenging assumptions—challenging the world as it is in relation to the world as it could be—was woven into the very fabric of the school’s pedagogy. “That’s a lesson that was very clear to me at CA,” he says.

And the school’s faculty members, he continues, honored students’ drive toward activism and involvement. “They knew it was a part of our growing into who we are.”

At the same time, Boris has learned, there are no Hollywood endings.

“Even if you accomplish what you set out to accomplish, the experience of that accomplishment, and all that happens as a result of it, is nothing like how you thought it would be, and only opens up the necessity for more action and more striving. It has to be about the going toward, rather than the arriving. In any given moment, I try to remain true to engaging at the intersection of what I have to give and what the world needs, and to do that as authentically and intentionally as possible. And then, come what may.”

A direct participant in change

Boris and his Navalny collaborators are considering a few possible follow-up stories in the wake of the Putin critic’s death. But regardless of what those may or may not be, he acknowledges, “I think we will always be there for the Navalny family and for the Anti-Corruption Foundation that he created. Every one of us who made the film or who’s touched it in any way will carry the lessons we learned from it into every project that we undertake.”

Boris is currently shuttling between California and Iceland, where he’s working on a new project in development with National Geographic, with his directing partner from Fire of Love, Sara Dosa. Alongside producer Elijah Stevens, the team is now running their own production company, Signpost Pictures. They are making a film about an Icelandic couple who were among the first to explore and photograph Iceland’s glaciers. In the course of just one generation, their grandson is now the first to eulogize a glacier’s death at the hands of anthropogenic climate change.

“Going out onto Iceland’s glaciers to shoot, we recognized that glaciers are dynamic beings,” Boris explains. “They support life, and they are also alive in their own way. By centering a story of glaciers in relation to humans, our film and our process are attempting to posit a framework of relationality between humans and non-human nature. Non-human nature is sentient, lives and dies, and can be killed en masse—yet this need not be.”

Documentaries, and storytelling in general, he goes on, are a crucial part of change.

“I think sometimes we can walk around in the world trying to optimize for, ‘How does this serve me?’ But you don’t necessarily have to take the path of least resistance. As CA graduates, there are so many opportunities—some familiar, some that might have been right in a previous time, some because they’re what someone else says you should do. It’s more important to be committed to exploring and intuiting and thinking deeply about what is right and true for you, even if the answer never comes. The accelerating pace of change is very real, and nothing is more important than building the capacity to adapt to that change by embracing mystery as part of who you are.”