In the main gallery of Colorado Academy’s Ponzio Arts Center, visitors marvel at the brilliant colors, surprising textures, and natural wonders depicted in poster-sized prints of students’ photos of Iceland, one of the summer destinations in CA’s Global Travel program. A group of 15 Ninth through Eleventh Graders explored the sparsely-populated Nordic island nation over eight chilly days in June, seeking to learn more about the country’s unique history, geology, wildlife, and sustainable innovation. They brought back with them a collection of stunning photos to populate the first Ponzio exhibition of the 2023-2024 school year—as well as new ideas inspired by Iceland’s efforts at the forefront of global action to combat climate change.

According to CA photography instructor Karen Donald, who led the group along with science teacher Dr. Autumn Amici-Lester, the aim of the trip was twofold: to capture the country’s spectacular volcanic and glacial landscapes while witnessing its progress in cutting greenhouse gas emissions on a path to the ambitious goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2040.

In Iceland, explains Donald, the climate crisis and the work that’s being undertaken globally to respond to it are visible almost around every corner. “You’re never far from Iceland’s iconic glaciers and the waterfalls that hint at their steady decline.” As the world experiences higher average temperatures and rising sea levels, Iceland is losing around 10 billion tons of ice each year, according to NASA.

The result is a national sense of urgency around reducing humans’ impact on the environment, which has led to impressive strides, such as the elimination of fossil fuels and single-use plastics throughout the country, not to mention a nationwide hydro and geothermal energy infrastructure that meets most of Iceland’s needs for heat and electricity.

Touring the country, as the CA students did over the summer, reveals first hand a uniquely symbiotic relationship between Iceland’s people and the environment, and the impact that its sustainability initiatives have already made.

Gas fumaroles and bubbling mud pots in geothermal areas give evidence of the vast stores of energy beneath the countryside, fueled by the same lava that flows beneath Iceland’s 32 active volcanoes. Facilities like the Hellisheidi Geothermal Plant, fed by heat and geysers from three volcanic systems, can be seen in natural areas generating green, sustainable electricity and hot water for heating. At the Blue Lagoon, visitors can soak in geothermal spa waters, and at any of the numerous waterfalls and glaciers scattered across the landscape, hikers can witness the important role that water plays in shaping and sustaining the island nation.

Visiting natural areas alongside sites where innovations are taking shape—such as the Hellisheidi facility, where a company called CarbFix is successfully capturing carbon emissions and permanently injecting them into underground rock—inspired the CA students. Caroline Hagen, a Sophomore who participated in the adventure, says, “I loved learning about the science behind all of Iceland’s renewable energy.”

Fire and ice

By design, what the students absorbed along their treks near volcanoes and glaciers became the central focus of their photographic work, assembled in the culminating exhibition, titled “Fire & Ice,” in Ponzio’s main gallery, on view from September 1–30.

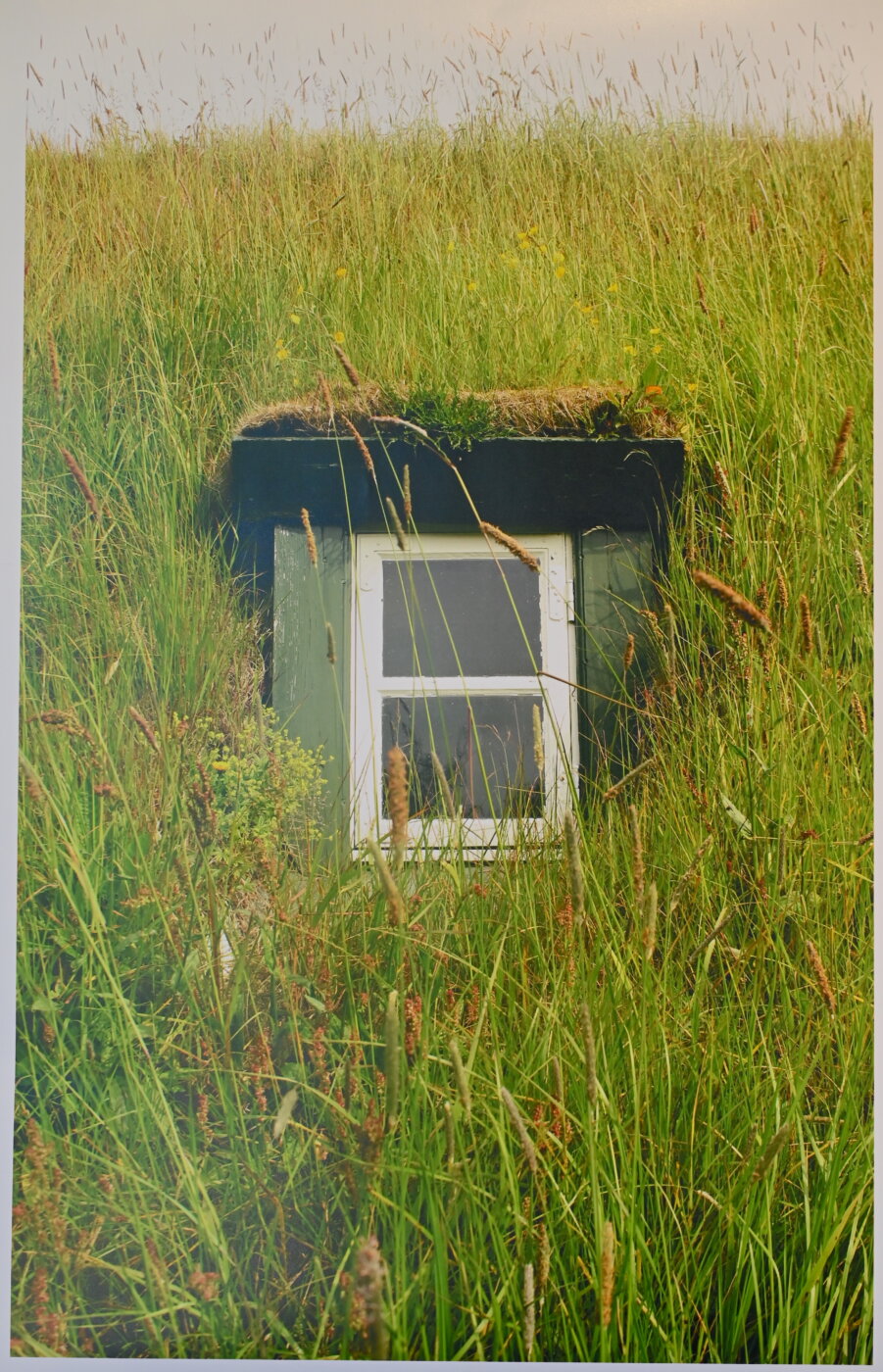

One eye-opening stop at Hofskirkja church in the southeastern part of the country allowed students to examine traditional Icelandic turf construction up close. As Senior Tyler Schulte explains of his striking photo of the church, “Turf has been used for centuries, dating back to the Viking Age, as a response to the harsh Icelandic climate. With a foundation of stone, and covered with layers of grass, turf buildings provide excellent insulation and protection against the country’s winds, extreme cold, and volcanic activity. Turf houses are not only aesthetically appealing, blending with the natural landscape, but they also offer remarkable energy efficiency, minimizing heat loss during winters and heat gain in summers.”

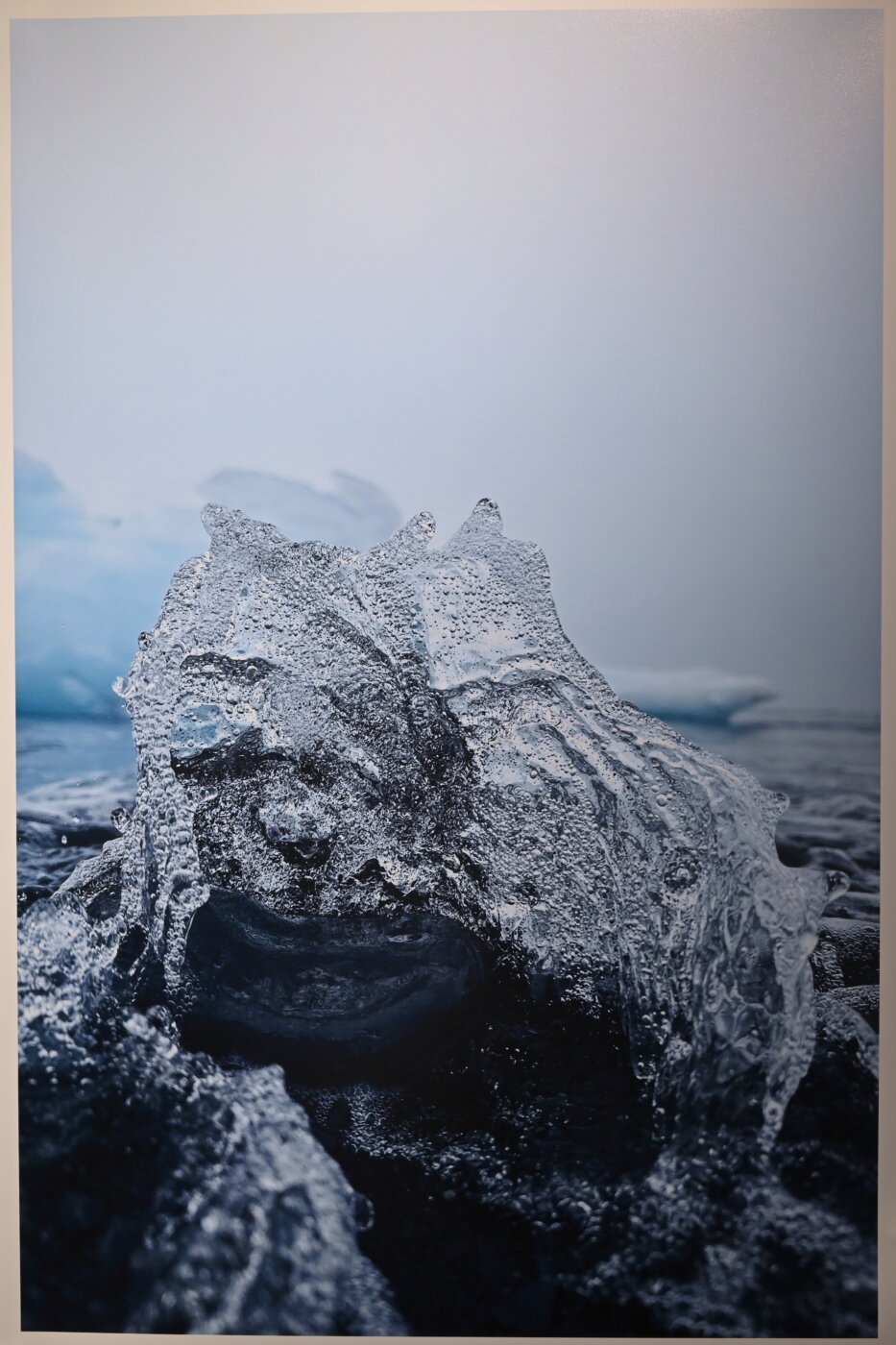

Junior Quinn London’s photograph of Jökulsárlón, a glacial lagoon, captures the changing life cycle of Iceland’s signature feature. The lagoon formed as the Breidamerkurjökull glacier receded, London notes, and, ”Due to climate change, glaciers such as Breidamerkurjökull are beginning to melt more rapidly. Not only does this mean natural phenomena such as glacial lakes will disappear, but also the excessive melting of permafrost can lead to natural disasters such as floods. Throughout our trip, it was refreshing to experience Iceland’s proactive and hopeful approach towards reversing the effects of global warming and protecting our planet.”

Dr. Amici-Lester’s deep knowledge of the world’s plant and animal life informed many of the students’ observations. In her irresistibly charming shot of an Icelandic goat on the Háafell Goat Farm, Junior Tierney Williams saw the story of the country’s concern for its threatened heritage. “Prior to the work of the Háafell Goat Farm, Icelandic goats were declining in number due to high demand. But the farm dedicated itself to preserving the Icelandic goat population, which is now thriving.”

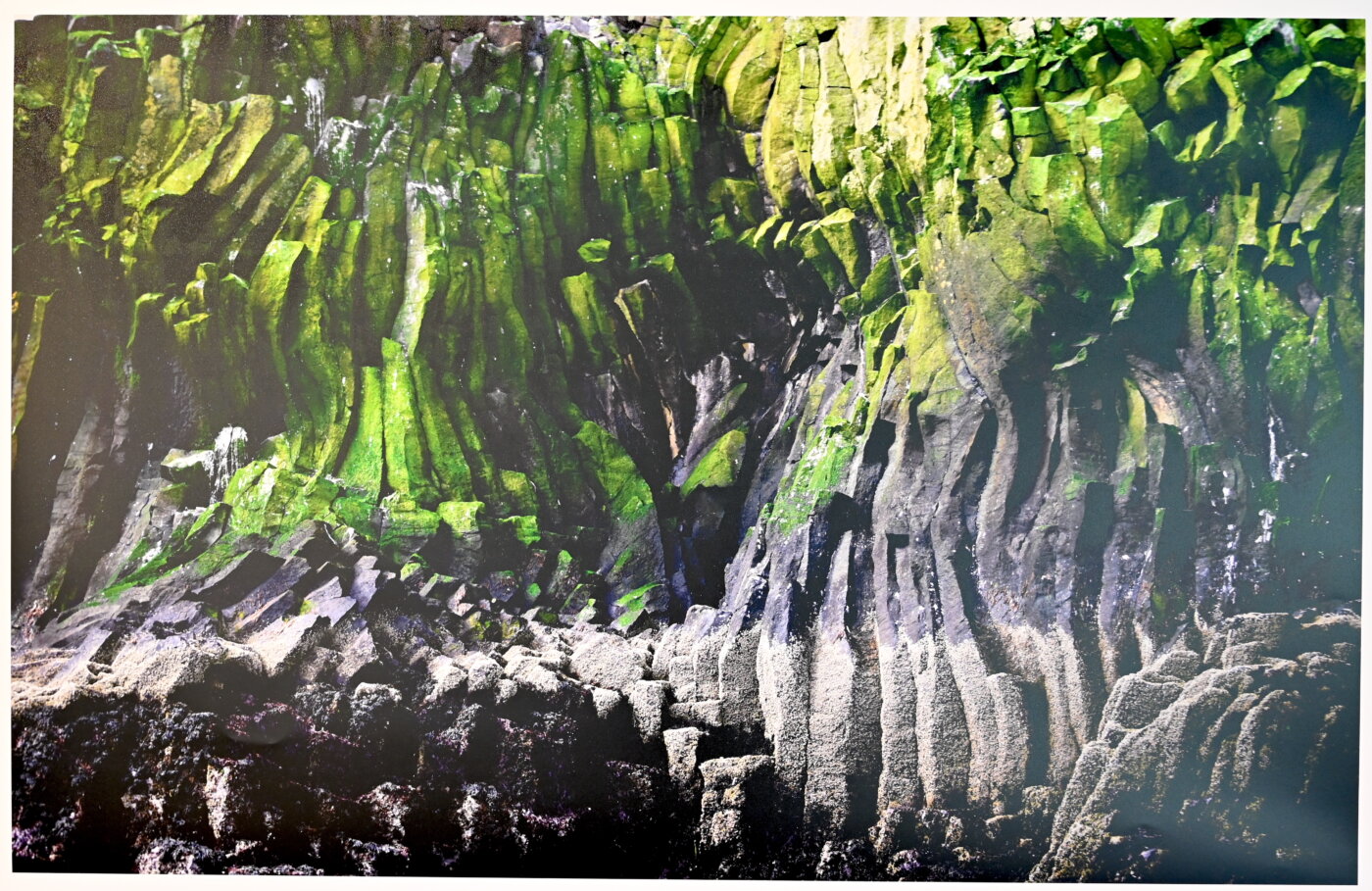

And on remote Melrakkaey Island, JD Westerberg found water, stone, and vegetation existing in harmony—symbolizing the many dependencies that define Iceland itself. “My photo captures the basalt walls of the island and focuses on the gradient of color, changing from the rough barnacles that are battered by the ocean to the vibrant green algae and mosses that coat the twisting columns of stone.”

“Over the course of our trip,” recounts Donald, “it was fascinating to see how the students’ understanding of the country began to deepen. Rather than snapping photo after photo of every waterfall and glacier we saw, as they did early in our itinerary, they gradually began to select moments to capture much more discerningly. The result is a collection of images that powerfully communicate the discoveries these artists most valued.”

Senior Allie Weil adds, “Going into the trip I already knew about my love for photography, but being in Iceland really helped me learn more about who I am as a landscape and nature photographer.”

Photography at CA

Encouraging students to slow down and explore the meaning of the photos they were creating was another major goal of the trip, Donald explains. “Here at CA, the mission of the Photography Department is helping kids move beyond the social media bombardment they’re experiencing every day and consider the purpose of image-making. We ask our students to consider questions like, ‘How can I make this photograph personally meaningful, and how can I creatively communicate that meaning to an audience?’”

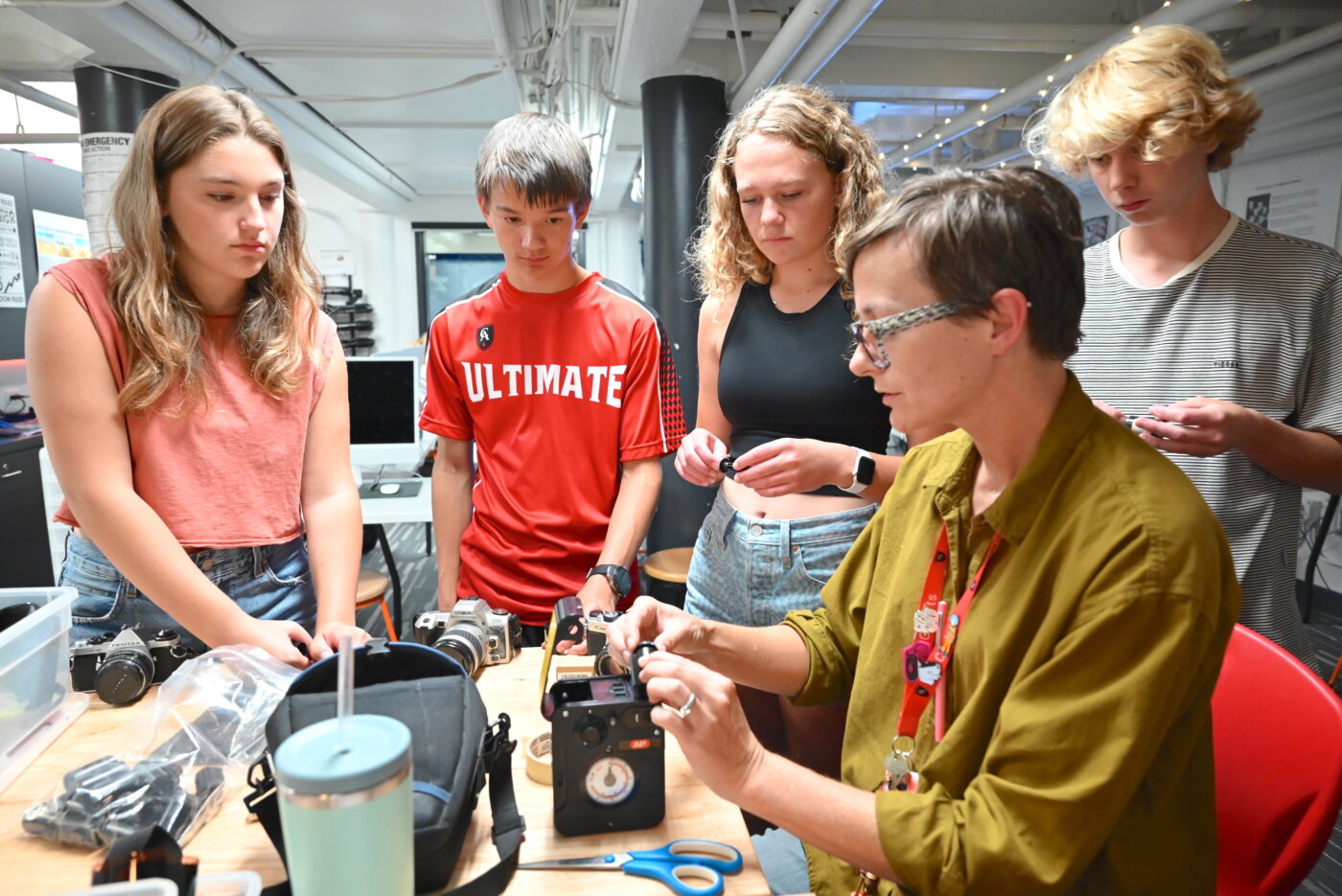

In her classroom, Donald urges artists to savor the beauty in the process of making photographs, especially when working with traditional techniques rather than the digital cameras in their phones.

“They come in perceiving photography as a quick, clean, realistic art. But when I have them make their own pinhole cameras and experiment with taking and developing their own pictures, they end up far outside of their comfort zone.”

The challenge, Donald continues, is getting students to think beyond the ways they’ve always understood photography. “I like to challenge them: What is it that you want to say as an artist? Can you manipulate your image to convey mood or atmosphere? Is there a social or political critique inside your work? I try to give them the self-agency to see that images can be powerful and layered with meaning.”

Carefully evaluating, printing, and displaying their work, as the students did after they returned from their Iceland trip, elevates photography to yet another level. “Once you enter the realm of the gallery,” observes Donald, “you have to consider how your work will hit audiences.”

A fact that’s often lost with today’s generation of camera-phone photographers, Donald goes on, is that viewers can have completely different relationships with printed photos rather than digital images on a screen. “When you see a photograph ‘in the flesh,’ your experience totally shifts. It can be very beautiful.”

That’s certainly true in Ponzio, where visitors slowly move from one vibrant image of Iceland to the next, the colors, textures, moods, and settings adding up to a complex picture of the students’ experience.

While Sophomore photographer Justin Schwartzreich says that the summer trip taught him “to get good angles and take low shutter speed photos of waterfalls,” the end result contains so much more.

“It’s not about the tools or techniques,” Donald explains. Even with today’s newest iPhones, which improve lighting, focus, and composition seemingly by magic, the challenge of photography remains: expressing the photographer’s intent through hue, shadow, form, and vision.