Right now, I am reading Donald Miller’s enthralling book Vicksburg: Grant’s Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. This excellent study captures the history of one of the most important events in United States and World history: the American Civil War.

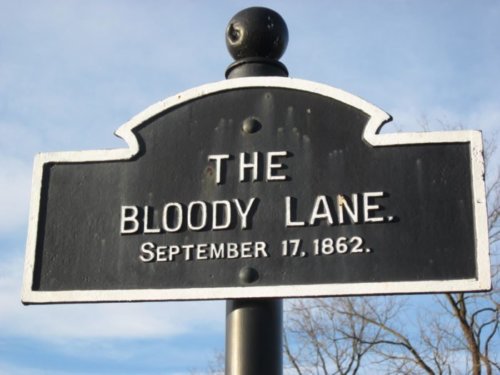

When I was a child, the Civil War was one of my favorite topics of study. I remember visiting the battlefields of Gettysburg and climbing the rocks of the Devil’s Den. Yet, it was my visit to Antietam that awoke a more fundamental understanding of the moral significance of the conflict. The carnage of that battle stuck with me, particularly along the 800-yard Bloody Lane, where 3,000 Union and 2,600 Confederate soldiers died in just over three hours.

Ending Slavery

The relative success of the Union’s effort at Antietam allowed Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which called for the freedom of African-American slaves held in Confederate States. It was a wartime measure aimed at helping undermine the Confederate’s military strength and dissuading European powers for siding with the Confederacy. Lincoln succeeded in ending human slavery with the ratification of the 13th Amendment, thereby eradicating the fundamental cause of the Civil War and beginning the long-term pursuit of equality under the law for all Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity.

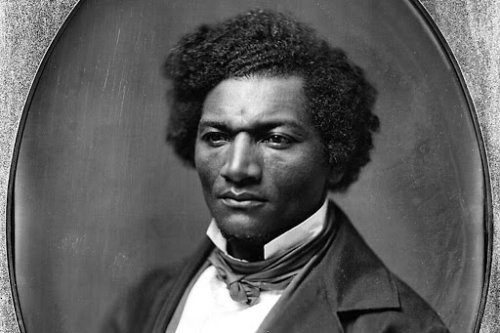

Lincoln was a masterful politician, and he succeeded where many of his 19th Century peers would have failed. Lincoln’s views on race and slavery evolved over the course of his presidency, and he, by 21st-Century standards, was in no way “woke.” To be sure, life events, his understanding of the meaning of the American Revolution, and the crushing burden of the massive loss of life in the Civil War influenced Lincoln to end slavery. But, intellectual context matters. Lincoln lived in a time when the argument about the moral injustice of slavery was dominated by the voice of Frederick Douglass. Besides Lincoln, Douglass stands as one of the greatest and most influential Americans of the 19th century. The two men had differences, and Douglass fully understood and was critical of Lincoln’s limited support for full civil rights for African Americans. Douglass’s contributions of drawing attention to the evils of slavery and racism, as well as to the furthering of human rights should rightly be remembered as we celebrate Black History Month.

The Power to Read and Write

Douglass’s life story is remarkable. Born into slavery, he escaped to the north and became one of the most influential abolitionists of his era. It was likely that his father was white. Like many people kept in bondage, he was separated from his mother at a young age. Sent to live in Baltimore, he was taught to read by the wife of his so-called “master.” The family to which he was enslaved quickly ended the lessons fearing the power that literacy and an education might provide young Frederick. He secretly continued his reading studies. He discovered books that opened his eyes to concepts of freedom and human rights. By 16, Douglass was teaching other enslaved people to read. He was sent to farmer with a reputation of “breaking slaves.” After being beaten and whipped, Douglass fought back. He wrote of the fight, “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.” By 1838, Douglass made his escape to the north and a year later became a preacher.

Through his writings and oratories, Douglass rose to prominence in the abolitionist community in the 1840s and 1850s. He was a living rebuke of the racist arguments slave owners would make to justify the enslavement of other human beings. But, Douglass was even more. He became an outspoken advocate for women’s rights and was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, an important gathering that advocated suffrage for women. He delivered a critical speech at that event that inspired momentum. He also advocated for the rights of Native Americans and Chinese immigrants. Even after the Civil War, he advocated for building bridges with former slave owners and those resistant to the expansion of civil rights for African Americans: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.” (A great message for those living in our current “cancel culture.”)

“Immeasurable Distance”

Douglass was courageous. Despite Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass did not endorse him in the 1864 election because Lincoln was slow to support suffrage for African Americans and the 13th Amendment. Yet, he would work with Lincoln. Here is a great Washington Post article on the relationship between these two formidable men.

You may begin to understand how even a famous person like Douglass would have experienced the intense racism of 19th century America and how he rose above it. Douglass wrote, “The distance then between the black man and the white American citizen was immeasurable.”

In his first meeting with Lincoln, he pushed Lincoln to pay African American soldiers serving in the Union Army the same wage as white soldiers, and to do more to protect African American soldiers from Confederate retribution. Douglass did not get all that he wanted, but Lincoln’s disdain for slavery and inhumanity convinced Douglass to continue to work with him. “Though I was not entirely satisfied with his views,” Douglass wrote later, “I was so well satisfied with the man and with the educating tendency of the conflict that I determined to go on with the recruiting.”

“A Sacred Effort”

The article shares the story of Lincoln’s inspiring second inaugural address. He personally invited Douglass to hear him share the famous words, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” In a receiving line, Douglass was prevented from seeing Lincoln, but Lincoln saw him and announced to other onlookers, “Here comes my friend Douglass.” Telling Douglass, “There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.” Douglass noted the solicitation of his opinion was “a sacred effort.”

I love history and the lesson it provides. In recognition of Black History Month, I encourage you to read The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, one of his three autobiographies. Also, David Blights’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom is an outstanding read or audiobook.

I think the story of Frederick Douglass reminds us the importance and power of courage, compassion, openness, and empathy. He reminds us that anything is possible with the right touch of humanity and a strong sense of justice.