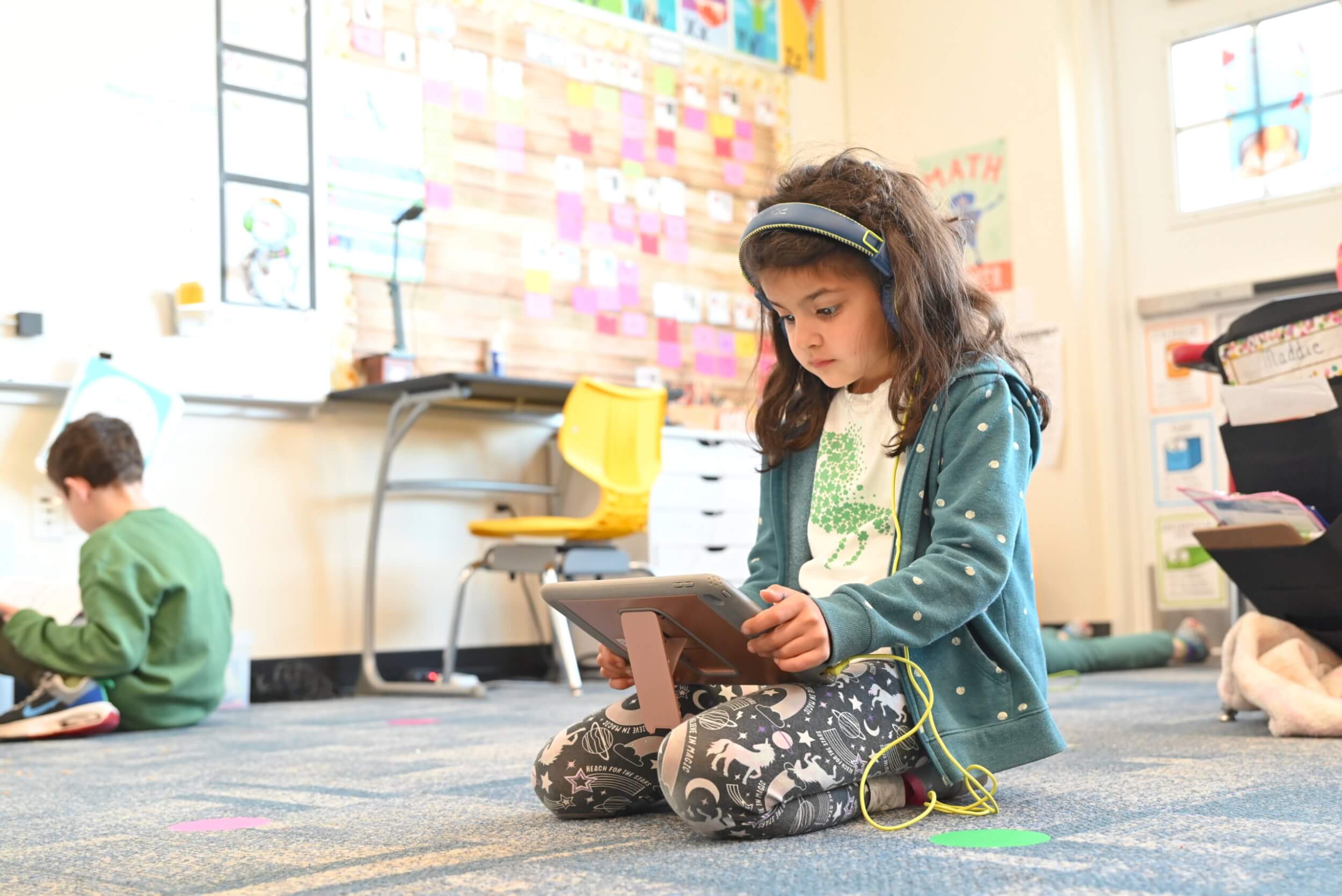

There’s a certain feeling that runs through Colorado Academy’s Lower School during literacy time, when students choose their favorite books from classroom libraries or work together over iPads in pairs and threes, while teachers provide small groups with direct instruction or support. It’s the thrill of empowerment, the excitement about the leaps CA students are continually making in their reading and writing—coupled with a sense of urgency about getting these foundational skills absolutely right in the all-important early elementary years.

Fueling it all is an emerging consensus about the research on the science of reading, along with an evolving debate over so-called “balanced” literacy approaches that until very recently held sway in elementary classrooms across the country. “Over the last 20 years, balanced literacy received a huge push in school districts and teacher education programs across the country. The science of reading has been more typically taught in advanced degree programs, so unless teachers pursued a specialization in literacy, they may not have had exposure to the research that supports the pillars of the approach,” explains First Grade Senior Instructor Megan Ollett, who holds a master’s in curriculum and instruction with an emphasis on literacy from the University of Colorado Boulder.

Agrees Cheryl Amador, Lower School Literacy Support Specialist, “There’s been a shift in our focus over the last several years as we look at emphasizing both the comprehension piece and phonemic awareness. We want to ‘meet in the middle,’ so that we are giving children a really strong foundation in word knowledge as well as understanding.”

With her master’s degree in curriculum and instruction with an emphasis in reading and writing from the University of Colorado Denver, as well as extensive training in structured literacy and the Orton-Gillingham approach in use at CA, Amador knows well that in order to be successful learners now and in the future, emerging readers and writers need a cohesive, evidence-based literacy scope-and-sequence that runs through the elementary years and beyond.

At CA, under the leadership of Lower School Principal Angie Crabtree, along with Amador and her fellow Lower School Literacy Support Specialist Debra Fenton, that has meant aligning Lower School classroom practices around the science of reading, a concept that informs literacy instruction with research-derived knowledge of how the brain processes written words. As opposed to “balanced literacy,” a loosely defined—yet immensely popular—set of practices that de-emphasize direct instruction in favor of often student-driven exploration of texts, structured approaches such as Orton-Gillingham recognize that more children become successful readers and writers when teachers carefully guide their acquisition of essential skills such as phonemic awareness, decoding, semantics, and vocabulary.

“As more and more children—not just at CA, but in every school—are being identified with learning differences, and we’re working harder to serve so many different kinds of needs in the same classroom, making sure that we are supporting every student with a coherent array of best practices is more important than ever,” Ollett observes.

‘Good things are happening’

What that looks like in the classroom may vary by grade and by teacher, but, as Amador explains, “All across the board, really good things are happening. With a robust literacy scope-and-sequence that goes from Pre-K all the way through Fifth Grade, we are able to draw from a wide variety of tools and resources to ensure that every child gets what they need in the classroom.”

That Lower School literacy “toolkit” includes such CA staples as Reader’s Workshop and Writer’s Workshop, which imbue daily sessions for practicing skills with meaning, purpose, and connection through peer feedback and discussion. In Kindergarten, for example, students work on their reading and writing by completing research on animals around the world and sharing their “dossier” of animal facts. By Fifth Grade, students are gaining fluency in a range of genres, including personal narrative and persuasive writing.

In Kindergarten through Third Grade, students use the online platform Lexia, a science-of-reading-based supplemental program that helps to accelerate the development of literacy skills so that students can make the shift from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” They use Explode the Code, a systematic, Orton-Gillingham-based method for decoding sounds and words. And across the elementary grades, readers and writers practice handwriting, vocabulary, and spelling using resources such as Vocabulary Workshop and Starting Comprehension, two series that focus on understanding text.

According to Second Grade Preceptor Jessica McCoy, who holds a master’s in culturally responsive teaching, “There’s no single ‘boxed’ curriculum that’s going to do all these things and still be invigorating and engaging for our kids. So we draw from a huge collection of materials, making sure that every teacher can access them.”

Adds Ollett, “We are lucky here at CA that we can be so flexible with our literacy instruction. Yes, we have all these opportunities for practicing skills, but at the same time we are able to incorporate multi-modal exercises that bring other elements like art, discussion, and personal expression into the conversation. We’re uniquely positioned to do both.”

“Being able to hit all of those pillars every day has brought a huge shift to the classroom,” says McCoy. “What we’re offering is truly balanced instruction.”

A concern for equity has also influenced the way CA’s literacy scope-and-sequence has taken shape in recent years, points out Amador. “Regardless of which classroom you walk into, or what previous school you may have come from, we’re able to meet every student where they are and make sure that everyone completes that grade with the same set of skills.”

“Educators today often talk about ‘cultural competence’ in the classroom; this is something that we’ve been doing all along at CA,” Ollett asserts. “Ultimately, being responsive to the students in your class and their needs—whether that is where they are in terms of their academic ability, social emotional well-being, or cultural background—makes up 90 to 95 percent of our job every day.”

Identifying strengths

CA’s two Lower School Literacy Support Specialists take that responsiveness to the next level, offering regular support and intervention for students who need something different to meet grade-level benchmarks.

“We are intently focused on the connection between executive functioning skills—emotional self-regulation, organization, time management—and reading and writing,” says Amador. “We know that a child who is working so hard to regulate their body and their emotions isn’t going to be able to approach reading and writing the same way as their peers.”

Amador and Fenton spend much of their time nurturing students’ awareness of how their brains work, normalizing conversations about slowing down their thinking or giving someone else’s brain a chance to get some exercise. Fenton, alongside CA’s Lower School counselor, Brooke Hamman, even runs a neurodiversity affinity group for Third through Fifth Grade students with a diagnosis of ADHD, dyslexia, dysgraphia, or discalculia.

“It’s been fantastic to work with these kids,” enthuses Fenton, a certified speech language pathologist with a master’s degree in communication disorders. “They get to see other really smart, bright, funny, athletic peers in the group and open up and share their experiences and strategies. What we tell them again and again is that though you may struggle in some of these areas, you also have amazing strengths that will let you shine.”

Fenton has spent her career specializing in the assessment and treatment of language-based learning disabilities, with dyslexia being the most common. Part of her role in Pre-K and Kindergarten is to help with the early identification of at-risk students so that prompt intervention can begin. “The earlier we can identify and support students, the better the outcome,” underscores Fenton.

Knowing a diagnosis is often empowering, Amador goes on, so the more conversations they can have with students and their families, the better. “Together, we build a learning profile, we create a roadmap for success, we put an accommodation plan in place, and we work with them to understand how their brain functions. We know they’re bright kids,” she says, “and we tell them that. We say, ‘How are you going to show the world your brilliance?’”

Constant communication is essential, not just with children and their families, but also among the Lower School faculty and staff. Fenton shares everything she knows about her Pre-K and Kindergarten students with Amador, who takes over with individual and small-group support starting in First Grade. The two, in turn, meet regularly with classroom teachers to exchange ideas and information and find out how they can reinforce each others’ work.

As McCoy explains, “At CA, we know every child. We’ve seen the assessments, we know what interventions are in place, we know exactly what areas a student needs support. I think one of the reasons our early literacy program is so strong is because of all the communication that we’re doing with Debra and Cheryl and our colleagues in the Lower School. It just feels really good for all of us to be on the same page.”

Magical powers

If there’s one hope that everyone in the Lower School shares for their students, it’s to inspire each child to love to read and write.

“We want them to know that being able to do these things is almost magical,” says Ollett. “Literacy is a powerful tool to ensure that their voice can be heard. They can share their ideas with others, they can access knowledge and information, and they can even escape into it.”

Amador insists, “Reading and writing are more than just decoding and making letter shapes. They’re about having conversations, about opening the world up.”

It’s no coincidence that this philosophy echoes the way teachers in the Middle School and Upper School view reading and writing, too. CA’s cross-divisional Literacy Committee, on which McCoy and Ollett both serve, ensures that the hoped-for outcomes of one division feed into the priorities of the next. “When we meet with teachers from the older grades, we always laugh when we find out we’re working on the same things,” Ollett elaborates.

In college admission offices around the country, CA is known for turning out graduates who are already critical readers and astute writers, well prepared to excel in undergraduate classrooms. That well-earned reputation starts in the Lower School’s homerooms, where a structured literacy approach meets differentiated attention and support to ignite the sparks that over the years grow into the blaze of effective communication.

And regardless of the debates that may continue in other states and at other schools about the best ways to teach reading and writing, one thing is clear: CA’s rigorous, evidence-based approach is unquestionably good for children and for the passionate readers and writers they will become.