The first time she came to visit Colorado Academy, in third grade, Leilani Abeyta ’18 recalls thinking to herself, “Are you serious?” The child of a working single mother, Abeyta was enrolled in a neighborhood elementary school, the youngest in her grade but at the top of her class. Her mother, Nina, dreamed of sending her to CA, and to Abeyta on that first visit the campus seemed like a dream indeed: the grassy playing fields and open spaces, the state-of-the-art facilities, and the teachers and coaches dedicated to helping students discover the best in themselves.

“My mouth was hanging open; I had the biggest, goofiest smile on my face the whole time—and I’ve had that same feeling every day since I’ve come back,” she says.

Admitted to CA with a financial aid package that would make it possible for her to stay all the way through high school graduation, the nervous Fourth Grader who hurried to adapt to a dreamworld of opportunities is now the newest member of the school’s Visual and Performing Arts Department faculty, teaching the innovative Studio Art course for Sixth Graders.

No one is more surprised at this than Abeyta, who finds herself instructing Middle Schoolers in the same Ponzio Arts Center classroom where she first discovered how big a role art would play in her own life. “I started as a nine-year-old; I left as a 17-year-old. And the way that CA nurtured my spirit through all of those years—without that, I would not be the person I am today: the best version of myself.”

After graduating in 2018 and then attending art school in Maryland until the COVID-19 pandemic brought everything to a halt in 2020, Abeyta returned to Denver to pursue her career in art full time. She painted murals around town on commission, joined the board of the urban art and activism lab PlatteForum, and began earning recognition as an artist with exhibitions at Union Hall and the Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as through the historical illustrations she completed for a Rocky Mountain PBS documentary about Barney Ford, an escaped slave who became an entrepreneur and civil-rights pioneer in Colorado.

In summer 2024, Abeyta was at CA teaching art to over 100 campers a day in the school’s Summer Programs, and only a few weeks into the gig, she ran into Katy Wood Hills, CA’s Director of Visual and Performing Arts—her former teacher and the person who is most responsible for pointing Abeyta down the path that took her to where she is today.

She had first met Hills as a CA Sophomore, in the Advanced Art class that Hills teaches each year. A born artist—“I drew non-stop from the moment I could hold a crayon,” she recounts—Abeyta was overjoyed to discover that at CA, “Art is something that is valued. In the Upper School, and even before that in the Middle School, the permission and the respect that teachers gave you allowed you to explore so many things artistically. I just felt a whole new world open up.”

CA hadn’t necessarily been easy for Abeyta. In Middle School, while she was the one who led the group of Eighth Graders that painted a beloved mural on the back of the former Froelicher Theatre building, like so many young people at that age, “I lost confidence in almost every area of my life.” As a financial aid recipient who at times felt intimidated by the academic and social confidence she witnessed in many of her peers, she often struggled to understand how her creative energy and artistic identity could fit in.

But by Eleventh Grade, in Hills’s class, she had found her answer; her passion and excitement for art had a home, and she, too, felt more at home than ever before. “Getting that validation as an artist—as someone who could be successful and be recognized for their gifts—gave me a completely different sense of belonging.”

Academics and art

Hills immediately saw Abeyta’s abundant talent and encouraged her to branch out from her preferred medium, colored pencils, into oils. Abeyta was resistant at first, both because she didn’t think she was any good at oil painting, and because she knew the materials were prohibitively expensive, but Hills found a way to assuage both concerns. She pointed out that the sophisticated way Abeyta liked to blend layers of color was already akin to oil painting; and she made it possible for her student to acquire her first set of oil paints and brushes through funding from CA.

The push from Hills was all it took for Abeyta to flip the script throughout the rest of her high school career. In Senior Instructor and English Department Chair Ross Holland’s Philosophy and Literature course, she earned high marks for an assignment she completed on the graphic novel of Paul Auster’s City of Glass: She illustrated her notes and ideas about the book in colorful, graphic panels that mimicked the style of the novel itself.

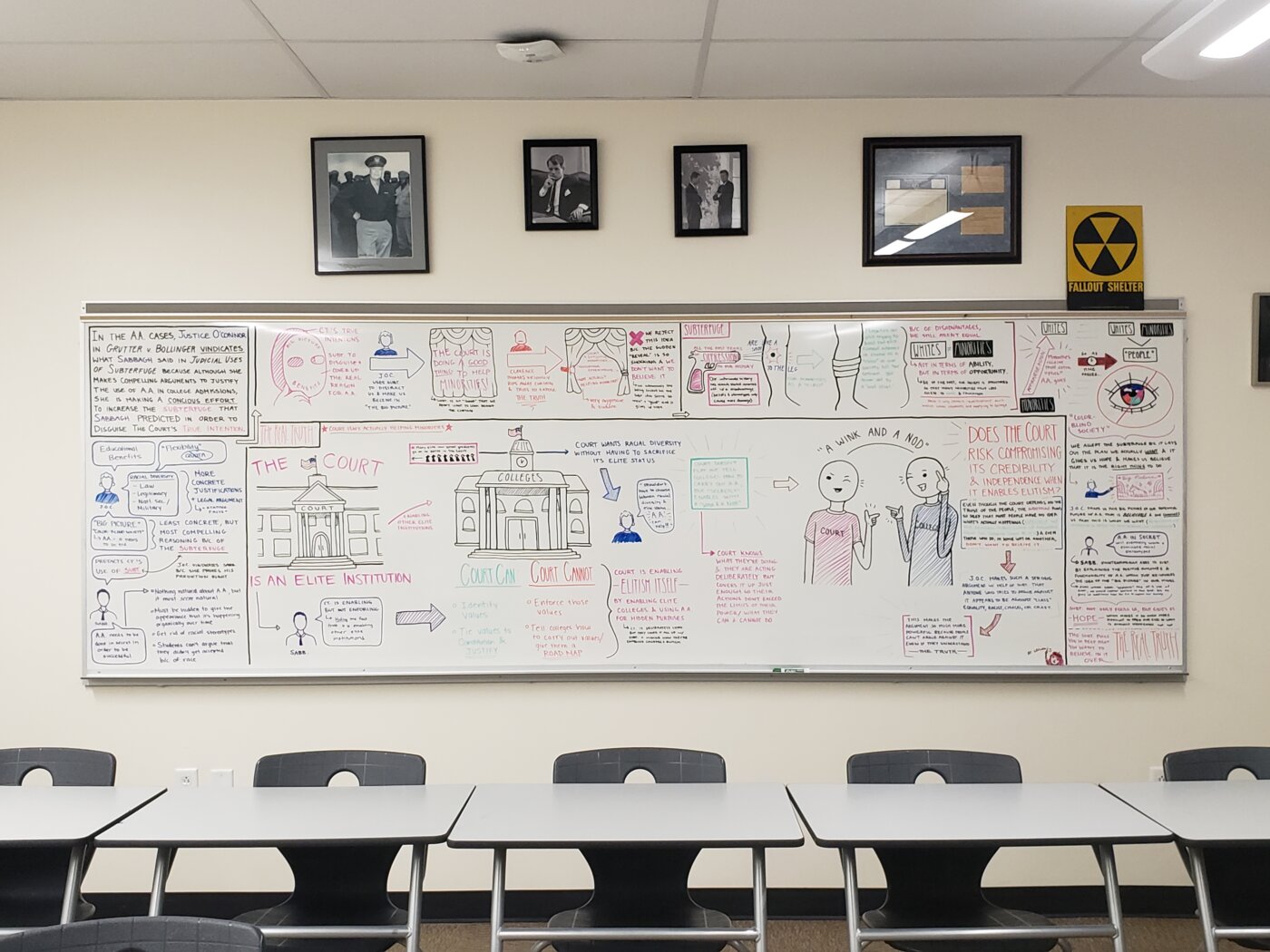

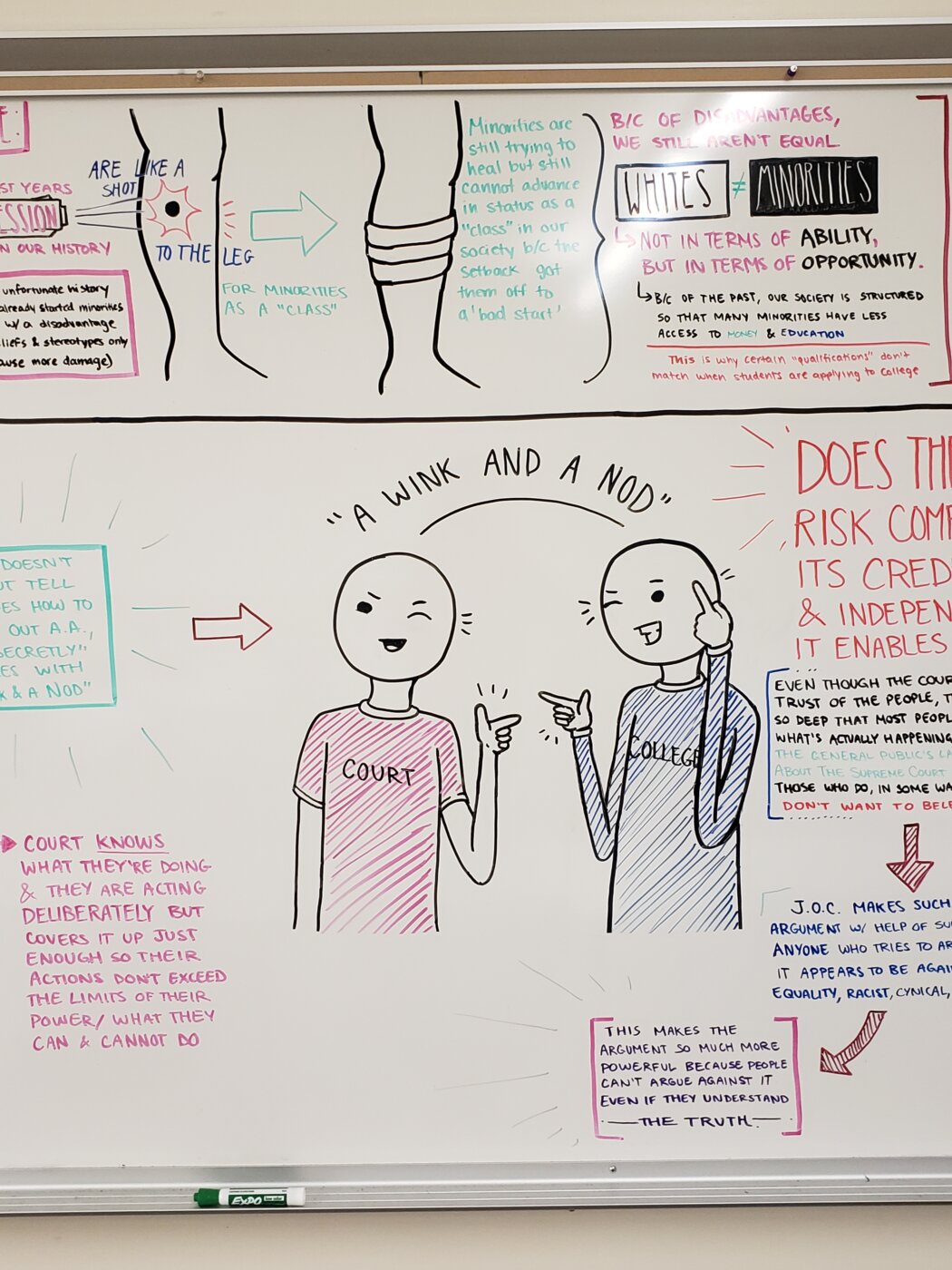

And in a Supreme Court elective with one former history teacher, a hugely respected scholar who was also a notoriously tough grader, she conquered any remaining academic insecurities for good. The class was examining the 2003 case of Grutter v. Bollinger, a landmark that upheld affirmative action in college admissions, stating that it did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. (The Supreme Court has since reversed that decision.)

“I was struggling with the text. I was already so scared and intimidated because I knew it was a really hard class, and my goal was just to survive,” recalls Abeyta. She went to meet with the teacher one day during Help Time, and in discussing the case with him, she suddenly got it. “The ideas wouldn’t stop flowing.”

But a problem remained. For this visual thinker, the prospect of capturing her insights in a traditional culminating essay felt like an insurmountable obstacle. She told the sympathetic teacher about her trepidation, and to Abeyta’s astonishment, he offered her the opportunity to complete the assignment in any way she wished.

She chose to fill the classroom’s 14-foot whiteboard wall with an elaborate series of illustrations depicting her conclusions about the Supreme Court Justices’ arguments in the landmark case. The next day, her visual essay captivated her classmates, and the one-of-a-kind project remains a minor legend among CA faculty members.

That turning point in the Supreme Court class brought Abeyta to a realization that has stayed with her ever since. “I had spent my entire CA career up until that point believing that, yes, I’m capable of something, but I’m not capable of as much as everyone else; I’m not academically talented. Then, because of that class, I actually discovered that I am. You can do both academics and art together—and maybe that means even more.”

An infectious passion

Abeyta’s incredible journey—“All the things that I’ve learned about being flexible, being adaptable, so that I can bring something good to the table, especially as an artist in a very academically focused environment”—prepared her well for the challenge and the joy of teaching.

According to Hills, “While visiting Leilani in the studio over the summer, watching her and the campers build a gigantic cardboard city, it was clear to me that she is not just a painter, but also has a gift in the art of teaching. Her students were so engaged. Her passion for guiding them through the creative process was clearly evident, and her love for it was infectious.”

Hills had been seeking a new part-time faculty member to support the growing Sixth Grade visual and performing arts program, and when she offered her former student the role teaching Studio Art, “It was so unexpected, I cried,” Abeyta admits.

Still, she quickly got down to work to put her mark on the curriculum, seeking help from fellow art teacher Jorge Muñoz on aligning the scope of her class within the broader Lower School program.

First and foremost, Abeyta’s class would emphasize process and progress. “It’s easy to get discouraged or feel confined when teachers impose blanket expectations for students’ work, especially at this age,” she explains.

“My goal,” she continues, “is to stop a lot of those harmful thoughts about art in their tracks and completely reshape the way that students approach it. Even if they don’t see themselves as creative or artistic, art still plays a role in everything that they care about.”

Abeyta also works to instill in her students the same sense of possibility that fueled her own creative growth. One day, she asked the Sixth Grade artists, “Does anyone have any ideas they don’t think are possible to do in this class?” When hands started going up, Abeyta called on each student and helped them see how, with creativity and flexibility, almost everything was possible.

“I just cannot wait to see what these kids make,” she emphasizes. “I can sense so much passion and enthusiasm in them, and I just want to be the person who’s along for the ride.” Teaching, Abeyta points out, has opened up a whole new side of her relationship with art. “Working over the summer at camp and now here in the classroom, I get to witness so much growth—the connections they’re making in their brains, and the connections they’re making with each other. This is such a huge transition point for them; they’re finding out so many new things about themselves.”

Renaissance woman

Each day in class, Abeyta adds to her students’ toolbox of new knowledge bits and pieces of the many practical lessons, techniques, and helpful tips that have propelled her own work from the days of completing her Senior Portfolio exhibition in Ponzio’s main gallery. That collection of hyper-realistic drawings and oil paintings included a portrait of a good friend, Head of School Dr. Mike Davis’s daughter, Eliza ’18, as well as a startlingly detailed rendition of an eye.

These early works hinted at everything that was to come, and they encapsulated the themes that have remained central to Abeyta’s art ever since. The eye, in all of its incredible details and technique, reveals just how important stubborn determination—to learn new things and to persevere—has been to her career, she says. “The eye showed me who I am and what my values are, which is why I emphasize process so much in my classroom.”

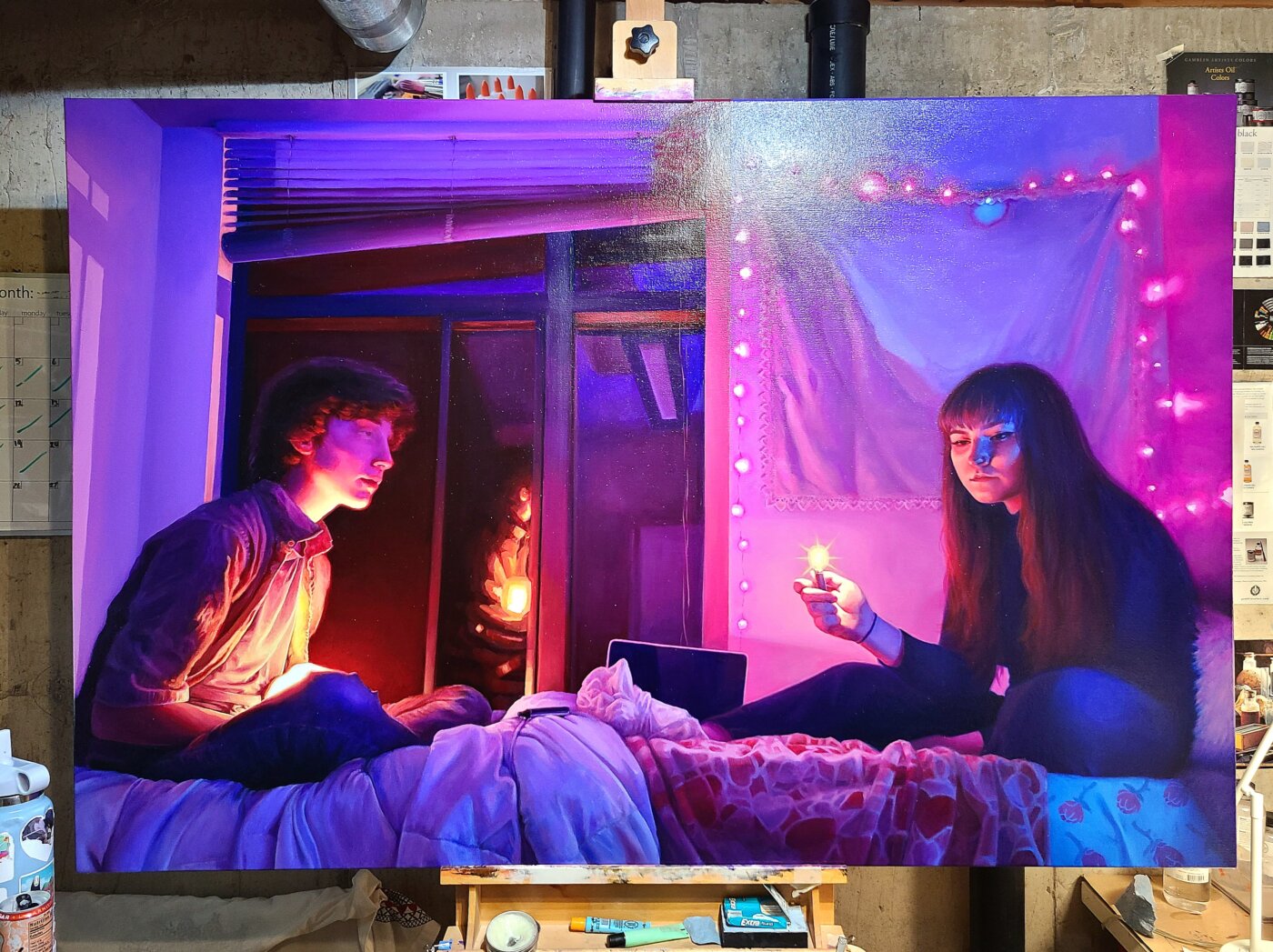

The portrait of Eliza Davis, too, contains a message that still resonates. The strikingly lifelike painting—which depicts the Senior with sparkling corn syrup dripping down her forehead—is sharp and pointed in its breathtaking immediacy and richness. It is one of the first examples of the Renaissance-inspired portraits that have quickly earned Abeyta recognition throughout the region.

“Most of what I paint is documenting the people I’ve known, my life and my memories, so when I’m gone, they will still be there.” At the same time, she says, “I’m obsessed with using the techniques of the Renaissance masters—the way that Da Vinci, Botticelli, Michelangelo, and others elevated lighting, color, and the human form in portraiture—but to represent contemporary life.” Adding the glow of a neon tube or a laptop to a subject’s face, Abeyta says, brings the past into today: Instagram by way of the 16th century.

Abeyta generates her intricate portraits from reference photos: Instagram-worthy snapshots or staged moments that somehow reveal the inner light she sees in the participants, her close friends. “Gabi & Thomas,” the painting that headlined Abeyta’s exhibition at Union Hall in fall 2023, started years ago as she sat with two college friends under a glowing canopy of lights and Abeyta suddenly exclaimed, “Please can I take a picture of you guys right now?” The result is a luminous, purple-and-gold tableau that is at once of-the-moment and timeless. Through the transformation of a photo into a painting, Abeyta is able to lend a certain magic to what’s real, making it “more” real. Perhaps what she captures is the way a cherished memory feels when we recall it—warmer, richer, more evocative than any singular moment of reality.

With a distinct vision and growing body of work to her credit, Abeyta has reached a point in her life, she observes, where she feels she is successfully making a name for herself in the art community in Denver. She’s already had her work shown in a couple more galleries this year, leading to new mural commissions, connections, and opportunities.

“And being able to continue this next part of my journey at CA is so meaningful to me,” she adds. “Especially being able to share all the things that I learned along the way with a group of kids who are growing and learning and changing—it’s just really, really cool.”