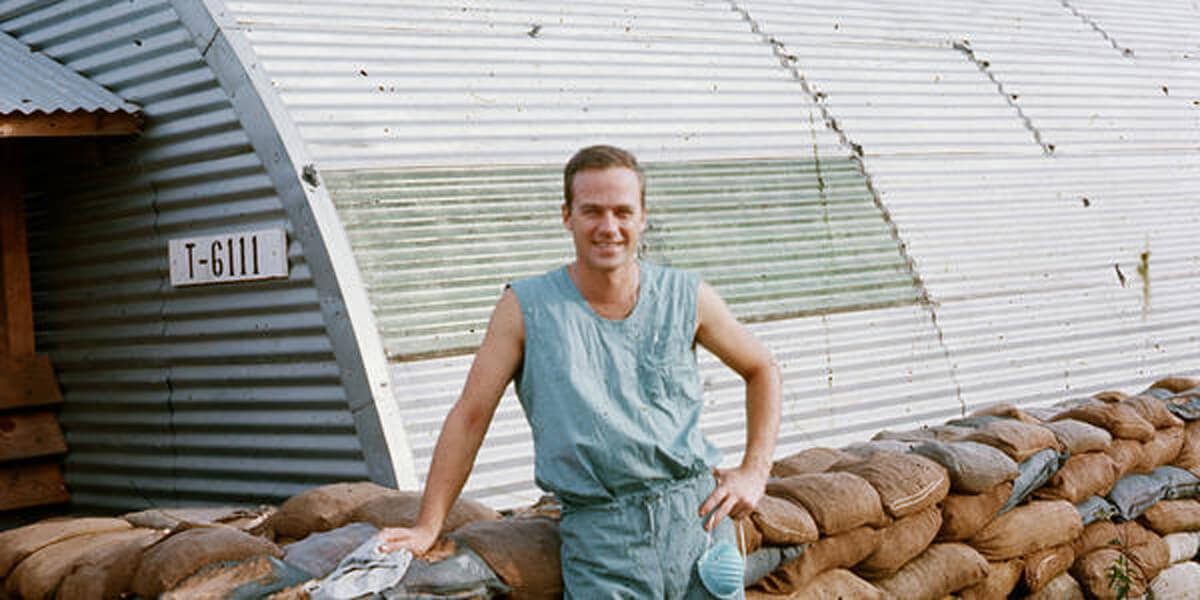

My father-in-law, Dr. Lawrence Jelsma, passed away recently after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease and was buried with Military Funeral Honors. Lawrence spent his professional career as a neurosurgeon. He cared for and ran a family dairy farm with great enthusiasm. Also, from June 1967 to the spring of 1968, he did a tour of duty in Vietnam.

Long Binh, South Vietnam

Lawrence was part of the 24th Evacuation Hospital in Long Binh, Vietnam. Long Binh was located about 20 miles from Saigon and was the largest base in South Vietnam. The 24th Evac Hospital was organized and began operations in Vietnam in January 1967. As one study notes, it started with 30 doctors, 60 nurses, and several hundred supporting personnel. By the end of the year, the hospital had grown from 200 to 400 beds. The hospital primarily serviced wounded Marines who were operating in three surrounding tactical areas.

At one point during his service, Captain Jelsma organized a neurosurgical unit at Chu Lai with the 1st Hospital Company, 1st Marine Division. (I believe he was awarded his Bronze Star for his efforts setting up that unit. He once described to me operating on soldiers at that location while nurses and corpsmen held up headlights from Jeeps so he could see.)

Lawrence rarely talked to me about Vietnam, even though he knew I had studied the war and taught about the conflict. He was always interested in what I was reading and assigning to my students at Colorado Academy. Periodically, he would share a memory or two, but there were no happy memories. During his tour of duty, the 24th Evac received 5,308 patients who required surgery. Of those, 733 involved head injuries and 139 involved back or neck wounds.

Because of the use of helicopters to evacuate the wounded, field hospitals were set up to specialize in treating various types of wounds. There was a constant flow of wounded to the base. At Lawrence’s funeral, a nurse who served with him spoke to me about the experience and what he was like to work with. She described the doctors as having to make hard decisions about who could be treated. Doctors like Lawrence treated not only American wounded, but also civilians and children. Sometimes they had to treat North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong wounded.

A powerful moment

A few years ago, I shared how my brother-in-law found Lawrence’s journal describing the types of operations and injuries he had treated. It is tough reading and reinforces why Lawrence, like so many veterans who have experienced combat or the effects of fighting, do not talk about their experiences. During his tour of duty, Lawrence performed more than 376 operations; of these, at least 330 were head injuries. He carried that weight with him through out his life.

Before Lawrence died, another veteran from his local community in Kentucky interviewed him, and wrote about what he learned. “The magnitude and extent of injuries were totally different from those seen in civilian practice. Injuries were extensive, causing an intensity of blood loss that Jelsma quickly learned to control, using the teamwork approach with both corpsmen and other specialists. Shrapnel from mortars, artillery, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) caused wounds that were very severe: stomachs ripped open, eyes blown out, legs blown off, etc. An IED is a homemade bomb constructed and deployed in ways other than in conventional military action. It may be constructed of conventional military explosives, such as artillery rounds attached to detonating mechanisms. Roadside bombs are a common use of IEDs.”

In Vietnam, the majority of wounds were from explosives, but up to 20 percent were head wounds. A wounded GI would be airlifted from the field to a hospital within 30 minutes. This allowed patients with severe head injuries to survive in ways they couldn’t have during WWII. Patients who arrived were horribly injured, and the surgical teams worked rapidly to save them. The doctors would then move to the next patient.

Several years ago, one veteran whom Lawrence had treated surprised him by showing up at his farm. This veteran had looked up the name of his physician on his medical records and simply wanted to come thank Lawrence for saving his life. It was a powerful moment for Lawrence and for the rest of the family.

Working 12-hour shifts

If you know your history of the Vietnam War, then you would have put together that Lawrence served during the Tet Offensive. During this surprise attack, the Viet Cong attacked the ammunition dump at Long Binh. You can find video of this explosion of thousands of artillery shells online. It looked to observers like an atomic bomb was detonated.

In an interview, Lawrence described working in 12-hour shifts for two weeks during Tet. “I will never forget the sound of an incoming helicopter. Each time the choppers came in, they were loaded with desperately wounded men. We ran to the operating room to get ready.” In another conversation Lawrence had with my own dad, I remember him describing how the helicopters just kept coming and coming for days and days.

Honor Guard and taps

At Lawrence’s funeral, there was a two-person Military Honor Guard. Taps were played, and it never sounded more beautiful. I am actually not sure I can truly describe it. There was something sad about it, to be sure, but the sound of the bugle seemed to hang in the warm southern air in ways that are hard to put into words. Then, the soliders performed the ceremonial folding of the flag, and a sergeant knelt and presented the flag to my mother-in-law with the words, “On behalf of a grateful nation…”

I am getting tears in my eyes just writing this, as it was a powerful moment that I won’t forget. Lawrence did not have a choice to go to Vietnam. He was drafted. But while he was there, he did all he could to help his fellow Americans and to serve his nation. He survived Vietnam and went on to live a full life; he lived to see his grandchildren grow to near adults. The same is not true for more than 59,000 Americans who did not return from that conflict.

Honoring veterans

I truly can’t imagine what this Military Funeral Honor ceremony is like for the families who lose their young sons or daughters during a military conflict, when that young person is full of promise. It is always devastating to lose a loved one, but the conditions and the senselessness of war undoubtedly make it more painful. The best I—and all of us civilians—can do is to try to understand. We can also show our respect for those who serve our nation and put themselves in harm’s ways to defend our freedom and liberty.

I hope you can take time over this Veteran’s Day weekend and next week to reflect on the service of all of those in our military and to thank those who serve.

I’d like to acknowledge the work and research of Ron Van Stockum, who interviewed my father-in-law and wrote a piece about him in The Kentucky Sentinel-News.