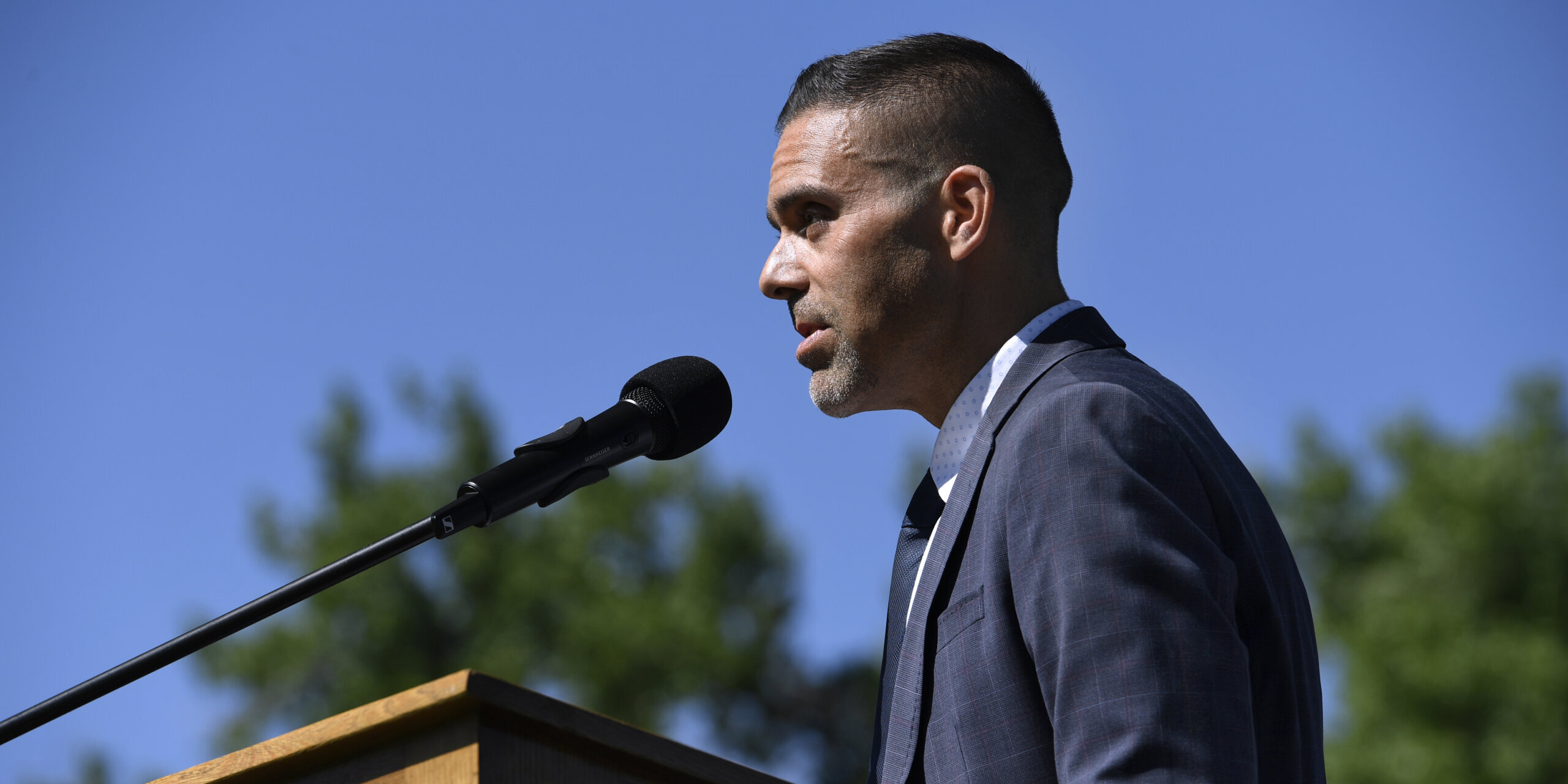

Good morning. Graduates, it’s my honor today to take a few moments to speak to you on behalf of the faculty who’ve had the JOY of watching you grow over these last four years. Like all of us, they’re eager to see what amazing things you’ll do once you get out into the world.

Now, at first blush, you may think your teachers’ primary job was to prepare you for the bigger world. But that’s just a half-truth.

Really, we saw our most important job as giving you the tools to live a meaningful life—a good life—because, in our optimism, we believe this is one of the best ways to ensure we leave the world better than we found it.

Now, a good life and good choices often go hand in hand. And you’ll have billions of choices ahead of you over the course of your life, but especially over these next handful of years.

I want to tell you two stories about choices and how they speak to a final lesson your teachers hope you take away today.

The first story takes place about 20 years ago. I had a friend, George, who, like all of us in our late twenties, was making choices he assumed would shape the next decades of his life.

It’s funny how we approach these kinds of choices differently. When the stakes feel high, we replace curiosity with calculation and wonder with strategy. George was no different. He worked his life like a Rubik’s cube—believing that precision combinations would make the colors match and solve the puzzle of adulthood.

Now, we all wanted and worried about different things. Personally, I was worried about finding a job and keeping it. But my friend, George, he really wanted to be married. He felt marriage would unlock all these things he longed for: children, a home, a person to walk through life with.

And then one day, something happened. A friend of George’s parents called him. “Listen,” the friend said, “My niece is visiting from out of town. I think you guys would hit it off. She’d love to meet you for a cup of coffee.”

George was delighted. “Where’s she visiting from?” he asked.

“Canada,” the friend told him.

“Sorry,” George replied. “I can’t move to Canada.”

Now, as George was telling us this story, our friend Aaron said: “George, she wasn’t asking you to move to Canada. She was asking you to have a cup of coffee.”

“Yes,” George agreed, “but if the coffee goes well, someday we might fall in love. And if we fall in love, someday she might ask me to move to Canada. And I don’t want to live abroad.”

Now, this isn’t the part of the speech where I tell you that we convinced George to go have coffee with this girl from Canada. Or that today they have three teenage children and a home in Vancouver. This also isn’t the part of the speech where I tell you that he missed out on the greatest love of his life because what do I know?

George’s love life isn’t the point of the story.

The point of the story is that in declining this coffee, George did what he was trained to do his whole life. It’s one of the things we’ve trained you to do. Plan ahead. Memorize algorithms and anticipate how they can be applied. Discard those applications that seem unlikely to produce your desired outcomes.

Focus.

It’s good that we taught you to do this. It’s why you’re getting your diploma today. It’s why you met your graduation requirements. And it’s why, after you leave here, you will do big things and finish what you started.

But this is only a half-truth. Because this is not the only thing we taught you.

Today, George will be the first to admit that, at 26, he thought he knew how his life was supposed to go. And the life he had planned didn’t include his living in Canada.

But today, George will also be the first to tell you that one of the tensions of the human condition is that we are constantly making decisions for a person who does not exist yet—our future self.

That person often has the same values as our present self, but they will have different lived experiences, heartbreaks, joys, wins and losses, which means they will have different priorities, different adaptive skills, and often make different choices than we might make today.

So what do we do with this?

Here’s another story. It starts back in 2010. I was 32 years old, living in Minnesota. My 16-year-old cousin from Mexico City asked if he could spend his Spring Break with me. Although we live in different countries, and although I’m much older than him, Ivan and I have always been very close.

In fact, he’d already spent a summer with me when he was 12. It was during that first visit that his mother, whom I love very much—but am also a little scared of—made me promise that I’d get Ivan back to Mexico safely.

In 2010, Ivan was 16 and wanted to visit me again.The problem was, although he was on Spring Break, I wasn’t. But I was a grade level dean at school in Minneapolis, and so I arranged for him to shadow some of my students for a few days, who were also his age.

It all worked out.

Seven years later, in 2017, Ivan was 23 years old. Again, he came to visit. As we were driving home from the airport, I asked him what he wanted to do while he was in town. It was all the normal things: Minnehaha Falls, the Mall of America, driving to Lake Superior. But then he added a caveat: “But Max,” he said. “I’m not available on Friday night. I have a date with Veronica.”

“Who’s Veronica?” I asked him.

He told me her full name.

“Ivan,” I said. “That’s one of my former students. From the Class of 2011. How do you know Veronica?”

“You had me shadow her when I was 16. We kept in touch.”

“Well, how often do you talk to her?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Once a week?”

Later that night, Ivan and I had a tense conversation on the porch while he waited for Veronica to pick him up. I gave him a curfew. And told him to answer the phone when I called. Needless to say, as a 23-year-old, Ivan was exceedingly annoyed at the idea of his 39-year-old cousin giving him rules.

I tried to defend my position, but then the real worry that had been chewing at my guts all week tumbled out. I recalled the promise I’d made to his mother back when he was 12.

“Ivan,” I said. “If you marry an American girl, your mother is going to kill me.”

“Max,” he said. “She’s not asking me to move to America. She’s asking me to go to dinner.”

It was then, of course, that I remembered George’s Canada story.

Although I’d made fun of George all those years ago, here I was, caught in the future while Ivan was focused on a simple question of the present: Do you want to go to dinner?

Let me be clear: Ivan was, and still is, a very focused and strategic person. But by youth, or temperament, or training, he was also able to think about the future without having a preconceived idea as to its outcome. He was able to hold his future loosely.

To engage in a strategic process while holding the outcome loosely is a mindset your teachers have been trying to instill in you from the start.

Think about the scientific method; think about writing a thesis; think about the art of analytical research. In all these things, process informs outcome. Not the other way around.

Have good process, and the right outcome will emerge.

Now here’s the good news. You excel at doing this.

As artists, you have learned that only by focusing on the process can you produce your best and most impressive work. As a class, two of you were recognized in All-State Choir; as a grade, you performed beautifully in eight main stage performances and excelled at all their complicated technical aspects. You flew through Mary Poppins, fought through She Kills Monsters, and fell down the hole in Alice by Heart. When touring the 23 Portfolio Shows you executed, almost universally you told us that your final product was inspired by the idea that originated it, but expressed in ways you’d never imagined at the start of the artistic process.

Athletically, you made a name for yourselves across Colorado, over the more than 400 competitions you engaged in this year alone.

Six DI athletes, seven DIII athletes, Boys Soccer 3A Player of the Year, Field Hockey Co-Player of the Year, Multiple All-State recipients, five State Championships, two State runners-up.

You made us proud, but let’s not forget what undergirds these achievements: the team. When you won, you won not by focusing on the final score, but by focusing on what the team was asking of you in that moment of the game.

But do you know one of the things your teachers will remember most about you?

It was how generous you were with each other during the awards ceremony two weeks ago. You cheered for each other in ways we rarely see grades do. You gave each other standing ovations, wholly celebrating those being honored and seemingly thrilled and proud to be in one another’s company. By youth, or temperament, or training, you showed us you have the capacity to savor the process and the outcome in ways that have impressed and inspired us.

If that was the good news, here’s the bad:

There will be times when adulthood will make you want to abandon process and discovery. You will be tempted to set aside wonder, curiosity, and open-mindedness for the sake of achieving a particular outcome. “I wonder what will happen next?” will not be a question that gives you joy. It will make you anxious because it threatens to upend your carefully laid idea of how your story is supposed to go.

At some point, you’ll find a Rubik’s cube sitting in your lap with all those mismatched colors, and you’ll want to fix it. Some adults spend decades trying to twist and turn the world into an order which they’ve convinced themselves is the only acceptable one out there.

You will be tempted to do this, too. It is not your fault. It is the human condition. It’s so easy for us to get tricked into thinking that if we’re smart enough, or work hard enough, or spend enough money, or make enough phone calls, or smile enough, or yell enough, or gossip enough, or bake enough cookies for people we don’t like, we can force the colors to match. We think if the colors match, everything will be okay.

Like most adults, I can’t tell you how many things I’ve messed up because I thought I knew how the story was supposed to go.

But here’s the funny thing—and here’s what your teachers, in their optimism, hope for you. The happiest people out there are usually the ones who’ve set the Rubik’s cube down. They’ve accepted the colors will never match. They’ve stopped trying to force it to go the way they think it should go.

Now your teachers don’t know what setting it down will mean for that future adult you. For some people, setting it down means saying “yes.” For others it means saying “no.” It might mean fighting for it or letting it go.

But what we can tell you is that, a lot of times, the right thing to do is whatever scares you the most, but is also the thing that makes your life bigger.

And Seniors, the reason I am telling you this, on behalf of your faculty, on your last day of high school, is that of all the lessons you’ve learned under their care, this is the one that’s hardest to internalize: Don’t assume you know how the story of your life is supposed to go.

Because someday, someone is going to ask you to consider a job you never knew you wanted.

Or ask you to move to a part of the country you’ve never been to.

Or ask you to stay when you wanted to go.

Or suggest a path you had no intention of taking otherwise.

Or maybe, someday, someone will invite you to a cup of coffee.

So wear it loose, even when it would feel safer to wear it tight and perfect.

Now, I’ve picked a lot on George today, so I don’t want you walking out of here thinking he didn’t learn to set it down. Often, when I’m future-tripping, or trying to force an outcome, he’ll just whisper at me over the phone: “Canada.” You’ll also be pleased to know that my aunt in Mexico has no plans to kill me. Ivan is currently in a very serious relationship with a lovely girl from Puebla who has zero interest in the United States and all our drama.

Educators by their very nature are optimists. This is why your faculty have spent their lives preparing other people to live their best lives. And so, as you prepare for your departure from this place that has loved you, we hope that you will carry some of our optimism with you. And like us, try to leave the world better than you found it.

Thank you.