I’m a sucker for historical fiction. While, as a historian, there are not many real accounts of war that I haven’t picked up, there are some stories that, set against the backdrop of conflict and sacrifice, crystallize the meaning of both.

In that category, put a long-time favorite book about the Civil War, the young adult book, Rifles for Watie by Harold Keith, published in 1957. It won the Newbery Medal in 1958, and in a mashup of fact and fiction, it tells the story of Jefferson Davis Bussey, a 16-year-old boy from Kansas who joins the Union Army in 1861.

It presents a little-known part of the Civil War, the campaign that unfolded west of the Mississippi—a conflict different and apart. Its separateness allowed for the protagonist to see the battle from both sides.

In the writing of the book, Keith apparently spent many years interviewing Civil War veterans and visiting the sites depicted in the book, resulting, as one reviewer put it, “in an authenticity that is rare for historical fiction.”

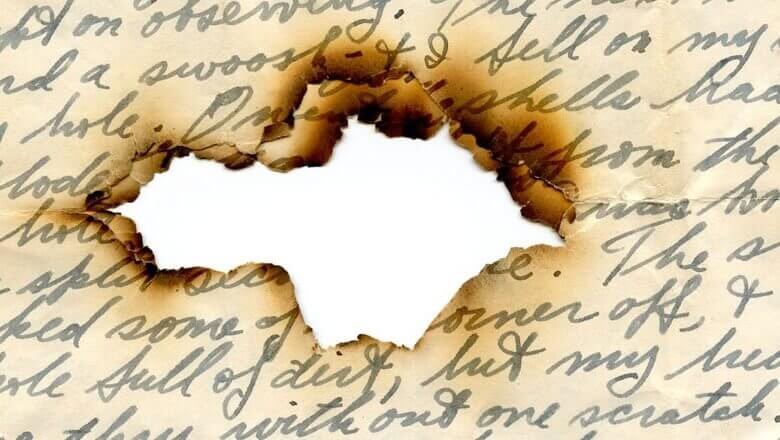

What was always compelling to me was how all of this was conveyed in the letters that Bussey wrote home.

There is something that is raw and urgent about what a soldier writes to his or her family—separated by space and time but drawn together in the immediacy of conveying thoughts and emotions, in case there is no tomorrow.

Housed at Chapman University in California is the Center for American War Letters. It is a remarkable archive and collection of war letters and emails from every American conflict, starting with the Revolutionary War and continuing through the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Says the university, “These letters and emails are an irreplaceable record of the sacrifices made by military personnel and their families, and they need to be preserved.”

Among the thousands of letters, here is just one from a World War II prisoner of war:

Notify: C.R. Kennedy, Maricopa, California.

Death of son Lt. Thomas Kennedy.

January 16, ’45.

“Momie & Dad: It is pretty hard to check out this way without a fighting chance, but we can’t live forever. I’m not afraid to die; I just hate the thought of not seeing you again. Buy Turkey Ranch with my money and just think of me often while you are there …”

In 1998, the historian Andrew Carroll launched “The Legacy Project” to encourage people throughout the U.S. to preserve wartime correspondence as a way of remembering the men and women who have served this country.

Since then, Americans have shared more than 100,000 previously unpublished letters and emails from every conflict in U.S. history. Mr. Carroll donated the collection to Chapman University, and renamed this project the “Center for American War Letters.”

As we honor Memorial Day on Monday and remember those who have died in military service for the U.S., I hope you might take a moment to visit these archives, read some letters, share a book or story with your child, or take a moment to express gratitude for what their service means to us.

While most of our Upper School students head out on Interim trips and experiences on Monday—a byproduct of our myriad efforts to schedule around AP exams, sports conflicts, and in the interest of keeping graduation still within the first week of June—it is no less of an important day for all of us to remember.