I gave a talk recently, and when I was being introduced, the speaker reminded the audience—and me—that I have been in a position of leadership in independent schools for nearly 25 years. After the event, I found myself thinking about the dramatic changes that have taken place over my time as an educator. I wonder if kids are better or worse off than they were 25 years ago? I am framing this for us to think beyond what happens at Colorado Academy, in terms of the American educational scene writ large. To what extent have schools caused these changes, rather than external factors related to social media and other cultural shifts?

There have been several trends and/or events that have fundamentally changed the nature of teaching and learning. We can argue that these trends and events have had both positive and negative impacts; and, as we always do at CA, we carefully assess how to implement new programming and curriculum.

This month, I thought I might dive into four major areas that have impacted education in this country: technology, more global competition and its impact on students’ sense of self, social and emotional learning, and the infusion of culture wars into schools.

Technology

When I first started teaching in 1996, technology was bare-bones. I remember creating my first course website and having to learn a little bit of coding to make it happen. Mainly, my website consisted of my syllabi, along with links to emerging historical archives and databases. As a history teacher, I saw the immense potential of connecting my students to primary-source documents. I remember taking hours of video footage from the Vanderbilt Television News Archive that I had copied for my advisor in a course he taught on the Vietnam War and converting it to a digital format. I had these huge hard drives that my students would use to download and study. Eventually, I got the videos in “the cloud,” and now my students make their own unique documentaries with the footage.

In addition, there was the emergence of student data systems that made it easier for teachers to create websites. Programs arrived to help grade more quickly and to create online tests and quizzes, as well as to detect plagiarism. Now we have artificial intelligence (AI) that will surely bring even more change.

During this period, students always outpaced their teachers in terms of adoption. Last year, we had an expert on AI come talk to the Upper School faculty and students. As he would mention a specific program, the kids would laugh as they already knew about it, while some teachers would be eagerly taking notes. My hope is that with AI we learn to work smarter. But for all the opportunities that the internet offered—it did not make us work smarter. As one thinker has noted, it actually just made us all a bit more distracted and disconnected.

This is particularly true for young people. While students have learned to do really cool things, like making websites, presentations, movies, and robotics code, technology use outside of school also can have a disruptive impact on learning. We know what the studies say about the impact of social media in particular. It offers new ways to harass. It makes kids feel like they are missing out. They see images of celebrities and social influencers living fake lives, and it impacts their self worth. Fewer students read for fun outside of school, and some college professors have noted that many students struggle with readings that students of 25 years ago would have had no trouble taking on.

Global Competition

While all this has been happening, we have seen the world get more and more competitive. For American parents, this is perhaps best understood through the lens of college admissions. Schools, particularly elite schools, have gotten ever more selective in the last decade as they made bigger outreach efforts to prospective applicants in all corners of the country and world. This has made many parents fear that there are diminishing opportunities for their children.

So, when parents began to see scarcity, the pressure campaigns on their children, their children’s teachers, and their children’s schools intensified. At my previous school, one mom diligently created clubs and hobbies for her children to build up their resumes for Ivy League admissions committees. They had tutors and test prep help—all the things one does to create every opportunity for kids. When I first started teaching, that was rare. Now it is far more common.

Thankfully, colleges have changed some of their approaches and are better at valuing students with authentic outside passions; and they are better at seeing which families might be “buying” experiences for their children versus encouraging them to drive their own learning. As well, students and families now embrace dozens of stellar colleges and universities. A recent trend we are seeing is students considering a wider range of schools—more large public institutions with school spirit, more geographically diverse schools here and abroad, and even more enthusiasm for warmer weather. Undoubtedly, negative reactions to the campus protests at elite Ivy League schools also contributed to this.

What is the impact of increasing competition? For one, stressed-out kids. More students than ever are grade-obsessed, rather than focused on what they are actually learning. It is far more common now than it was 25 years ago to have a student argue over an A-. Grade inflation at public and private schools has shot up. It went up particularly after the 2008 recession (among independent schools) and has not gone down. This is also true at elite colleges and universities. At schools like CA, that may be more understandable. We have an incredibly competitive admissions process and seriously motivated and talented students. But, I worry that if everyone just gets an A for walking in the door, we may cause serious harm when students eventually enter a workforce ill-prepared to produce real results.

As a parent with three adult children in the workforce, I know that getting to college is only step one. For those parents now worried about college admissions, my advice is to pace yourselves. Admission to an elite school is no guarantee of a job. Finding employment or going to graduate school now requires competing on an international level. At my previous institution, a boarding school, we had a significant number of international students. One of my favorites was an advisee from South Korea, who spent every waking minute studying and doing his homework. Still, this pressure on outcomes has not been good for kids.

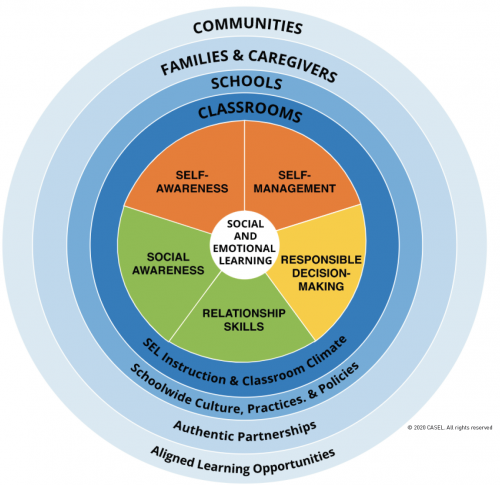

Social and Emotional Learning

So, how did schools respond? We began to focus more on social and emotional learning (SEL). I think we do an amazing job of this at CA in terms of balancing academic rigor with helping students develop emotional intelligence and resilience. Part of this remains embedded in Colorado Academy’s DNA from the days when we were a boarding school. But, on a national level, SEL has come under attack from certain groups—sometimes deservedly, as honest academic feedback can take a backseat to propping up emotions. This does the opposite of building actual resilience.

And given rates of emotional distress among younger populations, it does not seem to have been effective on a national scale. There are critics who argue that, at many schools, SEL is not effectively implemented. Given that so many American students attend schools with large populations, and public school teachers have such large classrooms, it is hard to forge the communal bonds needed to make SEL work.

But there is no doubt that a student cannot learn if they are in an environment where there is bullying, sexism, racism, or homophobia. There is an important balance to strike. We all need to remember that having emotional intelligence and cultural competence is essential for any future leaders. To be successful in the workplace, you need to be able to work with others and to be able to read the room. SEL helps develop those critical skills.

Culture Wars

The thing I worry most about in education is the impact of the culture wars in our classrooms, because it can silence debate and curiosity. As you know, we have tried very hard at CA to take up conversations about academic freedom and civil discourse. We want to empower our students to have tough conversations. But they live in a social world where that is challenging. When they watch the news or, more likely, see some type of video clip or story on social media, they don’t see a nuanced debate. They are in echo chambers of quick judgments and put-downs. That makes students far more reticent to speak up on controversial issues. I hear this from other school leaders, both on the K-12 level as well as at colleges and universities.

This is a challenge that schools cannot take on alone: It also depends on parents who are willing to model these conversations at home and encourage their children, as they develop and grow, to tolerate diverse viewpoints. As I drive to work, I switch between stations with differing viewpoints. When my kids were young and there was breaking news, we might begin by listening to CNN, and then I would say, “Let’s see how Fox is talking about this.” We would discuss what we heard. Our Speech and Debate program, just like all of our teachers, does a great job of getting students to think deeply and discuss tough issues.

Where we go next will be interesting. Schools are part of the larger society and culture. At CA, there are many ways in which we try to be “counter cultural.” We want kids to put their phones down and pick up a book. We want them to have a debate about a loaded topic and come away friends. We want kids to be involved in athletics and arts. We support specialization but also want our students to have a broad range of interests and skills. At the end of the day, we are raising human beings who, we all hope, aspire to be independent, productive, and good people.

One interesting thing that I and other longtime CA folks have noticed is a shift in mentality that happens over time as parents watch their kids go through the school. In the early years, parents are most concerned and most happy that their kids love school and learning. But, around Middle and Upper School, a focus on outcomes begins to loom large.

I would encourage all parents to hold on to a focus on the process of learning and growing; these are what lead to great outcomes. Indeed, that doesn’t happen without some level of failure. Just think of Simone Biles, one of the best gymnasts in human history. How many times did she fail before achieving success? Even before her gold medal performances in the last Olympics, you could see her fall during her warm-up.

Your kids are going to be okay! There is something special about our school, and that’s been true even as we’ve worked to ride the education trends of the past quarter century. If you have interest in learning more and thinking about these issues, here are three articles I read over the Winter Break that got me thinking about what we are seeing on the national level.

“Giving Kids Autonomy Has Surprising Results” – The New York Times (Download PDF)

“No, You Don’t Get an A For Effort” – The New York Times (Download PDF)

How Changes in PreK-12 Schooling Hampered Preparation for College – The Chronicle of Higher Education (Download PDF)