In their Earth Science class, Colorado Academy Sixth Graders are looking beneath the surface of one of the most pressing environmental issues facing the American West—the declining water levels in the Colorado River. Their fall unit of study, “Investigating Water as a Resource in Colorado,” introduces them not only to the basic science behind the water cycle in and around Denver and the Front Range, but also to the complex environmental, societal, and political considerations that surround any discussion of water in the region.

“Students know of the Colorado River, of course,” says Middle School science teacher Sue Counterman, “and it’s always been part of the Earth Science course, but this year we’re diving deeper than we ever have before. We’re looking at how the river is really the lifeblood of the American Southwest—and how historically low levels in the Colorado are affecting millions and millions of people.”

More than two decades into the longest-running drought in the history of the American West, the water levels in the Colorado River are so low that downstream states like Arizona aren’t getting the water they expected. Drought and rising temperatures due to climate change have accelerated evaporation from reservoirs, melted snowpack faster, and parched the soil. The result is less water available for agriculture, wildlife, and people, even as the population and the economy in the Colorado River Basin continue to grow.

“For me,” says Middle School science teacher Erin Galvin, “not having been raised in Colorado, it’s eye-opening to understand the importance of water in this part of the country. We want our students to realize that there are six major rivers that originate here in Colorado—with the Colorado River supplying water for seven states and parts of Mexico. We want them to start to make connections with things they’re hearing in the news and at home.”

Students begin their studies by learning about watersheds and gaining an appreciation of the fact that Coloradans all live in watersheds that feed the state’s rivers. What happens in those watersheds—from industry, agriculture, and recreation, to pollution, wildfires, and more—heavily influences water quality.

Sixth graders have the opportunity to learn about this idea through hands-on experiences at Woody’s Pond, an on-campus ecosystem that CA students have explored and enjoyed for decades. With the guidance of an educator from Denver Public Works, the students take samples of the water in the pond to study indicators such as turbidity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH.

Other lab work throughout the unit includes studying the properties of water molecules, testing for pesticides in simulated well water samples, and creating a hydrograph of the annual flow in the Colorado River near Granby, close to the river’s source.

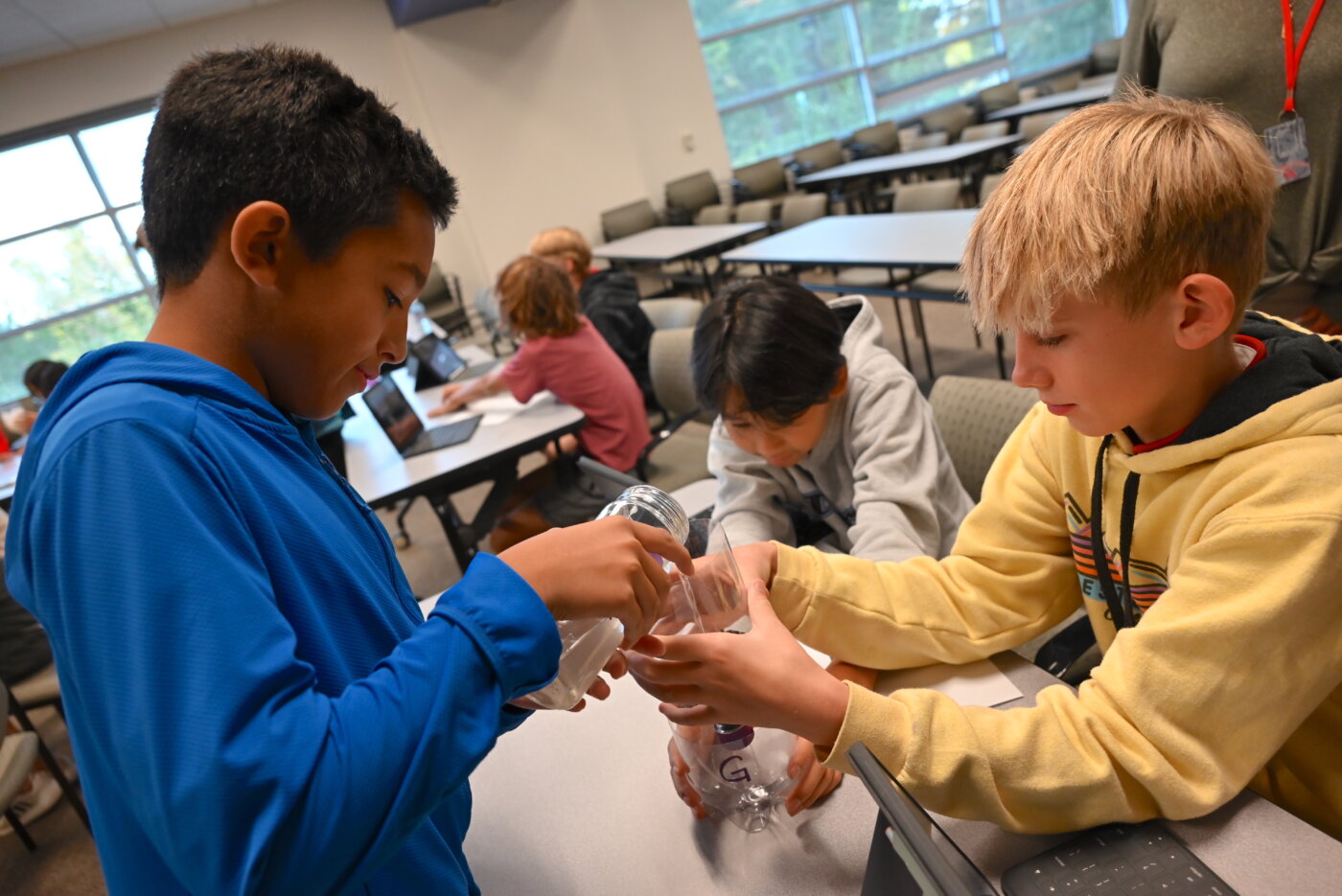

Later in the fall, Sixth Graders meet with a guest expert from Denver Water to learn about the path water takes from the Rocky Mountains to home faucets, discovering the science of the filtration process that makes the water safe for use, as they build their own water filters using a variety of materials including sand, wood shavings, and charcoal.

The students also construct their own watershed model to help visualize all the ways that humans—and the natural world—impact the vital supply of water that they depend on. As part of this project, they research the 2015 Gold King Mine wastewater spill, an environmental disaster near Silverton, Colo., that caused the release of millions of gallons of toxic wastewater into the Animas River watershed, which feeds into the San Juan River, a major tributary of the Colorado River.

All of these hands-on experiences, explains Galvin, drive home the point that we all play a part in protecting water as a resource. “The students start to ask questions like, ‘How do I take care of the watershed? What am I doing in my own home to conserve? What am I doing in my school?’ We want them to appreciate how fortunate we are to have the clean water we need today, and not to take for granted that we’ll have it tomorrow.”

“I’ve always felt that our students are so passionate about issues like these,” says Counterman. “And when we talk about something that’s so close to home, they really get engaged. We’re actually looking at things like civil engineering—the reservoirs and dams that capture the mountain snowmelt and send water to us here in the Denver area, the hydroelectric power plants that depend on the Colorado River to satisfy the demand for electricity throughout the West—and questions about how we plan society around water resources, how that has looked historically versus how it looks now. How can we help make the system sustainable in the future?”

Counterman and Galvin even introduce their students to topics such as the Colorado River Compact of 1922 and Native American tribal water rights, both of which are receiving new attention as states and the federal government are taking steps to try to address the crisis resulting from declining water levels and ensure equity while safeguarding a vital resource at risk.

Toward the end of the fall, Sixth Graders show what they know and dig deeper into topics that interest them through storytelling. They create narrative storyboards that trace the journey of a water drop, from evaporation in the Gulf of Mexico or Pacific Ocean, to condensation and precipitation over the Rocky Mountains, and finally to snow buildup and the spring runoff that fills natural aquifers, springs, rivers, and reservoirs.

“I find myself in a lake, surrounded by towering peaks,” reads one story by Annika Bhandari. “I am in a mountain lake in Rocky Mountain National Park. Suddenly, winds start to form and the air starts to cool. Then, after a few days of constant snow, the lake starts to ice over and I feel thick and heavy. I am solid.”

In another narrative, Emmaline Sprick writes, “I wake up to a soft rushing, and find myself flowing down the Colorado River near the confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers. What happened? Oh, that’s right: an avalanche pushed me down the mountains, where I landed in the river and must have melted.”

And Cam Reiter imagines, “On my way through the meandering turns of the Green River, I see wildlife and landmarks like the Uinta Mountains. I also see a lot of trash and factories. But despite the pollution, I see a rare fish, the humpback chub. This makes me really happy, and then I realize I just merged with the Colorado River.”

At the end of their studies, Sixth Graders take time to reflect on what they have learned about the crisis facing those who depend on the Colorado River—and on the ways that people are working together to address it.

Seeing images of the dried-up Colorado River delta, once a vibrant wetland, where it flows into the Gulf of California in the Mexican state of Baja California, Caroline Freitag wonders, “Are there water restraints in Mexico? Are they getting all the water they need?”

Adds Lydia Blessing, “I really appreciate how hard scientists and community members are working to help the river. I believe we can come back from the tragic state of rivers all over the world.”

And Rome Ryan observes, “There is still hope for humans and the ecosystem.”

While the Sixth Grade Earth Science class moves on from the Colorado River to a global focus on the world’s water, Counterman is passionate about keeping local issues front and center in her students’ minds. She has led an Interim trip to the Western Slope in the spring that reprises the themes from the Colorado River unit in the fall.

Exploring the inspiring, water-carved landscape of the Colorado National Monument, near where the Colorado River passes through Grand Junction, says Counterman, “It all becomes so much more real. My whole goal is that my students take water in our state personally, and this is a great way to make that impact.”

“If we can give our students a reason to care,” Counterman continues, “then maybe we have a chance to build a more sustainable future.”