The nation has experienced significant loss, and I felt it important to take a moment and reflect on the lives of two civil rights giants. Rev. CT Vivian and Congressman John Lewis died on Friday. Both were pivotal figures alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. in leading nonviolent protests against segregation and racism. Their lives serve as a moral example for all Americans of how we can stand up to injustice. They channeled their faith to take down a system of de jure segregation, that is discrimination enacted by law, that defined life for African Americans in the south. After making significant contributions to help shift public opinion on the immorality of segregation, both continued fighting other forms of racism in this nation. All along the way, they tried to bring people together to help us form a “more perfect union” in ways that reflected their Christian values.

Rev. CT Vivian

Although Lewis may be more well known, CT Vivian was a foundational figure in the civil rights movement. Vivian was a founding member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Along with Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Vivian was part of King’s inner circle of advisors. He led trainings in nonviolent, direct action and organized civil rights protests throughout the south as the National Director of the SCLC. He led sit-ins and boycotts of businesses to draw attention to racial segregation. These efforts provoked violent reactions by segregationists.

As the New York Times notes, “Televised scenes of marchers attacked by police officers and firefighters with cattle prods, snarling dogs, fire hoses and nightsticks shocked the national conscience, legitimized the civil rights movement and led to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

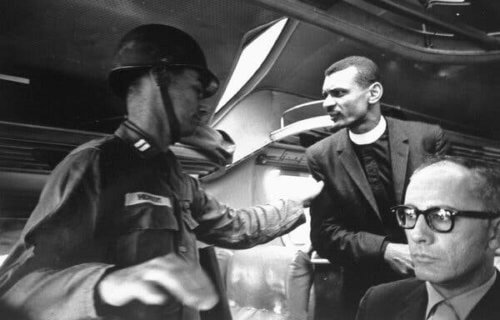

Vivian often put his life in danger for the civil rights movement. In 1964, he was almost drowned during a protest in St. Augustine, Florida, when segregationists attacked African Americans on the beach with chains. In another encounter in 1964, Vivian confronted the notorious Alabama Sheriff Jim Clark, who was blocking more than one thousand blacks from registering to vote. In front of cameras, Clark punched Vivian in the face and then ordered him arrested. Although we unfortunately still see examples of racial violence in this nation, Vivian once noted: “Going to Mississippi in 1961 was a whole different world. You knew you could easily be killed there.” Vivian later noted “Nonviolence is the only honorable way of dealing with social change, because if we are wrong, nobody gets hurt but us… And if we are right, more people will participate in determining their own destinies than ever before.”

Vivian’s life intersected with Lewis through these nonviolent demonstrations. Lewis also put himself in harm’s way repeatedly to advance civil rights. Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders. Before the Civil Rights Act, traveling between states was incredibly burdensome and dangerous for black men and women. The Freedom Riders were black and white activists who would ride in buses and then attempt to enter “whites only” spaces in restrooms and restaurants. The riders were often beaten and arrested. They did not resist or fight back and let themselves be subject to attack. Watch this short film about the Freedom Riders and note the diversity of this movement.

Congressman John Lewis

Lewis was the founder of the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee that led lunch counter sit-ins in southern cities. He also organized the famous March on Washington in 1963, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. Lewis was younger and perhaps more radical than King and other leaders of the movement. He spoke to the crowd before King, raising the level of energy. In words that foreshadow the same demands of the current social justice protests in this nation, Lewis spoke these words at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial: “By the force of our demands, our determination and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy. We must say, ‘Wake up, America. Wake up!’ For we cannot stop, and we will not and cannot be patient.”

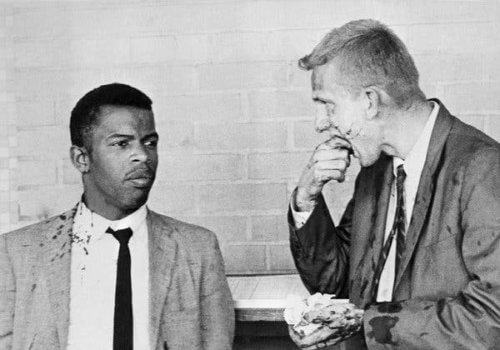

Lewis was fearless. The Times noted in his obituary: “Mr. Lewis was arrested 40 times from 1960 to 1966. He was repeatedly beaten senseless by Southern policemen and freelance hoodlums. During the Freedom Rides in 1961, he was left unconscious in a pool of his own blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal in Montgomery, Alabama, after he and others were attacked by hundreds of white people. He spent countless days and nights in county jails and 31 days in Mississippi’s notoriously brutal Parchman Penitentiary.”

When King organized the March on Selma to help raise public awareness for voting rights, Lewis was on the front lines. State troopers told the protesters to disperse. When they didn’t, the troopers attacked with tear gas, bull whips, and rubber hoses wrapped in barbed wire. Film crews caught Lewis being beaten by a state trooper. The national outrage to the violence of the segregationists against peaceful protesters led to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Passage of this landmark legislation eventually enabled Lewis to become a congressman in 1986, when Georgia voters sent him to Washington. He was only the second African American congressman elected in George since Reconstruction after the Civil War. In his time in congress, Lewis never moved far from his activism. He continued to speak out for civil rights and racial injustice.

For both Vivian and Lewis, the power of King’s message of nonviolence was critical to the success of the movement. Vivian recalls: “It was Martin Luther King who removed the Black struggle from the economic realm and placed it in a moral and spiritual context. It was on this plane that The Movement first confronted the conscience of the nation.” Despite being beaten, arrested, and threatened, both men were willing to forgive. They understood that reconciliation was critical. In 1988, Joseph Smitherman was the mayor of Selma and invited Rep. Lewis to return to accept a key from the city. What stands out in this is that Smitherman was the mayor of Selma when Lewis was attacked there in 1965. Smitherman, who had moved away from his segregationist stance, said at the ceremony: “Back then, I called him an outside rabble-rouser. Today, I call him one of the most courageous people I ever met.” Lewis has said of encounters with former segregationists who have apologized to him: ““Nonviolence and forgiveness is not just an idea, but it is a way of living for me.”

I hope you can take some time to read a little more about these great men and appreciate their contributions to American history.