Spanning the entire curriculum from Pre-K to Grade 12, the Spanish language program at Colorado Academy embraces bilingualism and celebrates culture, underscoring the school’s commitment to educating truly global citizens.

More than that, says Upper School Spanish teacher and World Languages Department Chair Lisa Todd, Spanish at CA acknowledges heritage speakers as a vital part of the CA community, and recognizes just how important Spanish language and culture are to our national identity.

“Spanish is a language that is so alive for our students,” Todd says. “It doesn’t feel ‘foreign’ to them—there are so many members of our own community who are native speakers of the language with their family and extended family.” She notes that many CA students encounter Spanish in the greater Denver area through volunteering with programs such as HOPE and Horizons Colorado.

“Historically, bilingualism has been devalued and even stigmatized in our culture, including in our schools,” Todd continues. “Making Spanish a priority at CA helps to undo some of that harmful legacy.”

As Middle School Spanish teacher Sara Monterroso points out, CA students, teachers, and families no longer see bilingualism as an “extra.”

“Whereas many Americans decades ago didn’t believe it was necessary to learn anything other than English—seemingly the world’s universal language—we’re now realizing that those bilingual global citizens outperform us in many ways, and that Spanish plays a powerful role in the business, trade, and politics of our region.”

The ability to navigate the world across cultures, says Monterroso, is the one thing she hopes her students take with them when they leave her classroom. “If they can understand their own culture or themselves better because they’re willing to reflect back through what another person’s eyes might be seeing, then that will serve them whether they go on to do business in Latin America, or the Middle East, or Southeast Asia. Language learning is really about intercultural understanding.”

Lower School

In Lindsay Bababekov’s Lower School Spanish classroom, a ukulele leaning against a whiteboard, ready for action, hints at the approach to language learning for CA’s youngest students. Singing, dancing, music videos, and games are central for students in Pre-K through Grade 5, exposing Lower Schoolers to essential Spanish vocabulary, such as the days of the week, the weather, colors, numbers, and greetings, along with useful verbs such as “I want” and “I have.” Fun, daily routines give these students the basic tools they need to start building phrases and sentences.

“They’re learning without realizing it,” explains Bababekov, who taught herself the ukulele specifically so she could more easily incorporate music in the classroom. “Singing, repeating common greetings, and noting each day’s date and weather teach sentence structure and verb tenses that are the building blocks for communication.” They also ensure that language acquisition is always a positive experience, nurturing an openness to language and culture that can last a lifetime.

Visual cues are everywhere in Bababekov’s classroom and that of her colleague, Lower School Spanish teacher Rita Vera. Posters and artwork illustrate the meaning of core vocabulary and serve as instant references when students are searching for a word. Classroom rules, such as “Raise your hand” and “Try your best,” are translated into Spanish and prominently displayed. These, combined with the teachers’ use of gestures and sign language, form the basis of the “comprehensible input” approach to acquisition that provides the foundation for the Spanish program in the Lower School.

“Comprehensible input is about providing exposure and increasing our students’ understanding through context, without memorization or explicit instruction in grammar,” Bababekov says. “The goal is to lead the class almost entirely in Spanish, and to get the students listening to and speaking the language as frequently as possible, even if they don’t understand every word.”

This style of teaching goes hand in hand with another well-known methodology, “Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling,” or TPRS. In this approach, students experience a second language in much the same way native speakers first absorb their own: through constant repetition of an ever-expanding list of words and phrases. This happens by way of varied techniques that include role-playing, gesturing, and plenty of moving around to both communicate meaning and engage learners.

Creative projects, such as student-designed mini-books composed in Spanish, Spanish-language art, holiday crafts, and maps and diagrams with highlights labeled in Spanish, give students experience translating ideas into a second language.

By the time they reach Grade Five, students have journeyed through numerous thematic units in Spanish, such as the parts of the body or Latin American culture. They can greet and hold simple conversations with classmates, and they can even do basic research, putting together oral and written presentations in Spanish.

The goal, Bababekov says, is building excitement and curiosity around language and culture. “Appreciating what is outside of our ‘bubble’ is so important. When you learn a second language, it just opens so many doors to who you can communicate with and what you can do with it. It’s such a great tool for life.”

Middle School

Students arrive in the Middle School Spanish program with a wide range of language experiences, points out Monterroso. Sixth Graders moving up from the Fifth Grade at CA are usually quite comfortable with Spanish. But because Sixth Grade is such a popular CA entry point—welcoming new students from all across the Denver metro area—some Middle Schoolers come with advanced abilities, hailing from language immersion programs or from households where Spanish is spoken. Others may show up with little exposure to Spanish at all.

As a result, the Middle School program is built for flexibility, accommodating all students by placing them in one of four learning levels. Spanish A, B, and C represent a typical three-year progression from “Low Novice” to “High Novice” proficiency (widely used standards established by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages). Students move from expressing their ideas in short phrases around familiar topics in Spanish A to using complete sentences to carry on simple conversations in Spanish C.

A fourth option, Spanish Language Arts, is an immersion course designed for native or heritage speakers of Spanish, as well as Eighth Graders with advanced skills. In this unique offering, various assignments expose students to different styles of writing and communication, spur discussion, increase cultural competence concerning historical and cultural differences among Spanish-speaking countries, test research skills, and emphasize spelling and grammar through targeted exercises and hands-on practice.

Spanish Language Arts, explains Monterroso, was designed with the support of Middle School Principal Bill Wolf-Tinsman and Middle School Spanish teacher Donna Farrell to better serve the increasing number of heritage speakers bringing their wealth of linguistic and cultural knowledge to the CA community, and to accommodate those traditional language learners truly passionate about Spanish. It is a virtual “one-room schoolhouse,” where students’ interests and strengths come to the fore, says Monterroso.

“The Eighth Graders in the room have usually ‘tested in’ to the course,” she says. “So they may have a very solid structural understanding of Spanish. But they realize they’re sitting next to students who might have much more organic exposure to Spanish language and culture, either because they speak it at home or come from an immersion environment.”

At the same time, continues Monterroso, those older students may have study and writing skills that the younger ones don’t. “So we capitalize on each other’s strengths and support each other in whatever gaps in knowledge we may have.”

But whether they are beginning Spanish learners or experienced heritage speakers, Monterroso explains, the focus remains on communication. “Today, our program is very usage-based,” she says. Where a previous generation of students may have spent the bulk of their time memorizing technical elements like verb tenses, CA Middle Schoolers, says Monterroso, pay much more attention to how they are growing as speakers and listeners.

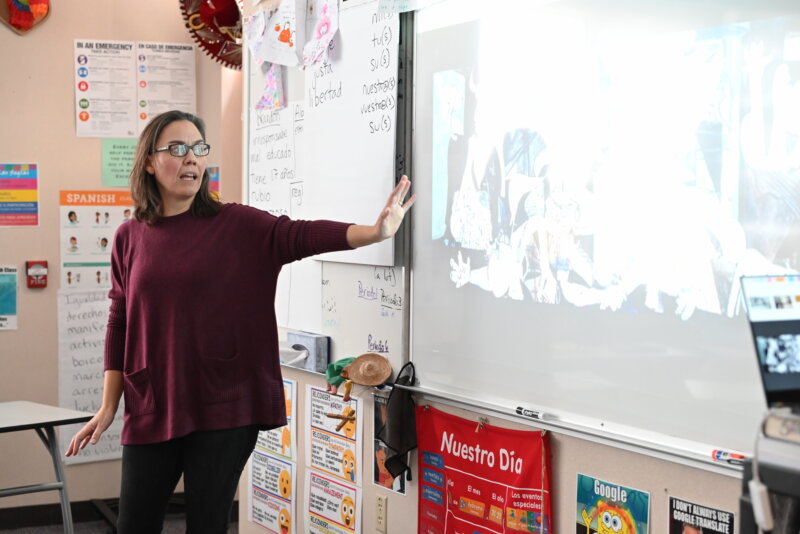

“Is a student still going word by word,” she says, “or can they pick up on phrases and even use complete sentences when they are communicating?” Monterroso and her colleagues use plenty of authentic recordings, videos, and other materials to expose students to the natural sounds of Spanish, and by the time they reach Eighth Grade, most Middle School learners can follow simple conversations, speak about common topics such as travel, hobbies, and family members, and even consult real Spanish-language sources for information.

“Yes, it’s ‘survival Spanish,’” acknowledges Monterroso. “But you don’t need a huge vocabulary to talk about some significant concepts.” She points to one classroom discussion where students compared transportation systems in Colombia and Spain. “My students could talk about riding a bicycle versus driving a car, and ask questions to learn more.” Similarly, when students listened to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” in Spanish, they could easily pick up on the Spanish words—segregación, marcha, arrestar—that sound similar in English.

“Sometimes all it takes is helping kids gain confidence with the language,” Monterroso says.

Upper School

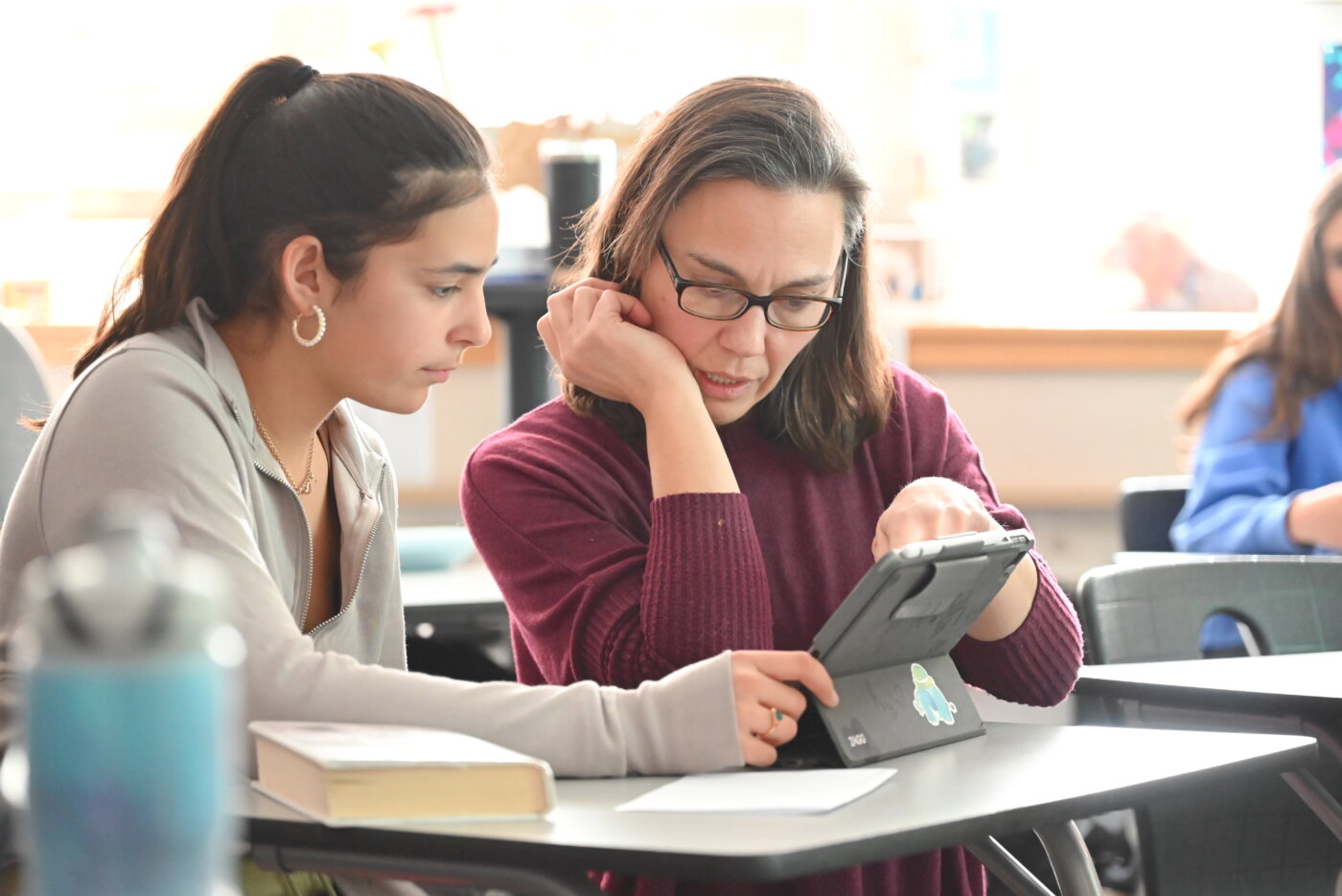

Upper School Spanish students spend even more time focusing on conversation. Communication, says Todd, is the ultimate goal of the program at this level.

“In the Upper School, we want our students to become lifelong speakers of the language, able to engage in true back-and-forth exchange. Conversation isn’t just one person nodding and rehearsing in their head what they’re going to say when the other finishes speaking. It’s built jointly through listening and asking follow-up questions.”

Students new to the language follow a standard four-year progression through Spanish I, II, III, and IV, by the end of which they are increasingly comfortable expressing themselves in speaking and writing.

Spanish for Heritage Speakers, like the Middle School Spanish Language Arts course, offers students whose home language is Spanish an opportunity to study the language formally in an academic setting, developing their reading, listening, writing, and speaking skills and examining current events and political and socio-economic issues facing the Spanish-speaking world.

Along with heritage speakers, those language learners who come to the Upper School already experienced in Spanish can progress to honors- and AP-level courses, where intensive and nuanced practice in all areas of language acquisition enables learners to broaden their knowledge of Spanish and Spanish-speaking cultures. Honors courses ask students to speak and write authoritatively and insightfully in Spanish about themes such as culinary history or film. In AP courses, students complete college-level work in Spanish language, culture, and literature.

CA’s AP Spanish offerings represent the real capstone of the program, Todd says.

AP Spanish Language, a prerequisite for AP Spanish Literature, emphasizes using language for active communication, reading increasingly complex texts, and developing more sophistication and accuracy in speaking and writing, while exploring the culture and literature of the Spanish-speaking world.

The AP Spanish Literature course requires students to engage in sophisticated analysis of 500 years of Hispanic literature, writing and discussing exclusively in Spanish as they progress through a significant canon of work. Students must delve into the history surrounding each selection, because, as Todd points out, “Understanding literature means understanding the context in which it was written.”

Succeeding in the AP Spanish courses represents a significant achievement, according to Todd—a point that was brought home by one recent advisee who was enrolled in AP Spanish Literature.

On a college tour, she recounts, the student was asked to list the books they had read that year. “My advisee made two lists, one in English and one in Spanish, and the Spanish list was significantly longer,” Todd recalls.

Just as in the Middle School, authentic materials play a large role at every level of the Upper School Spanish program. In the last few years, this has become easier than ever, says Todd.

“There are so many great Spanish-language shows available on Netflix and other services,” Todd points out, noting the growing body of research affirming that watching movies and TV shows with Spanish captions—reading and listening at the same time—is one of the most powerful ways to master a language. “There’s no better feeling than when we finish an episode and they want to watch the next one. They’re building such a positive connection with the language that they want to continue doing so outside of my classroom.”

Language connects people, Todd emphasizes. Conversing across cultures depends as much on interpersonal skills as it does on linguistic fluency. “I love that I can share that with students so that they can make new connections in their own lives.”