Look up Paul Robbins, PhD ’85 on LinkedIn, and you will see a message that communicates his passion for people and their planet.

“We’re not saving the earth. We’re saving each other.”

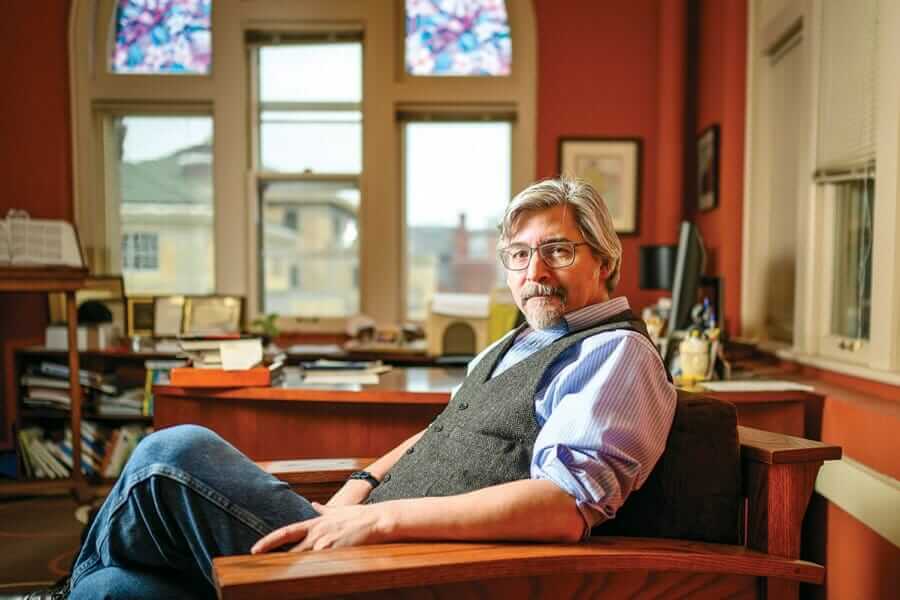

Coming from him, that is not just a platitude. As Dean of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Robbins is devoted to educating the future scholars, educators, and researchers who will tackle the toughest environmental issues that we face. On those subjects, he was ahead of his time.

“I was teaching about climate change in the mid-’90s,” he says. “I taught water resource management, and it was pretty clear what was going to happen. There would be increasing water scarcity in some places and increased flooding in other places. Climate change is a complex puzzle that people will have to solve.”

Robbins describes himself as a “glass half-full guy” who remains positive about the future. To some degree, he traces that outlook to his time at Colorado Academy.

“I credit CA with being focused on problem-solving,” he says. “Teachers would say, ‘Here is the challenge,’ and then we would be given the freedom and time to try to figure it out.”

Since he graduated from high school, Robbins has built a career that reflects his time at CA in many ways.

“I’ve moved forward in the world with skills I gained at CA,” he says. “Interdisciplinary thinking, respect for arts and sciences, the ability to speak in public, tech theater—that is all in my arsenal.”

‘You fall in love with the land’

Robbins’ first stop after leaving CA was the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He still remembers the surprise of meeting the Midwest.

“I looked out the window, and I saw lakes,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Do they just leave all this water lying around?’”

He majored in anthropology, but he now calls himself a “recovering archaeologist” after he traveled to India to do research as an undergraduate. “I fell in love with living people as opposed to dead people,” he says, with a laugh.

He earned his PhD in Geography at Clark University, returning to India to do research for his dissertation with the support of the Fulbright Scholar Program and the National Science Foundation. In the northwestern part of India, he studied political ecology—the relationship between environmental change and politics.

“The land there is a struggle,” he says. “It’s a place where people work out their problems. That only became super clear to me after I had been in India for quite a long time.”

In retrospect, Robbins can see that his fascination with land issues may have started on a VW bus when he was a student at CA.

“At CA, we would jump on a bus and drive to Utah to rock climb,” he says. “Growing up in Colorado, you fall in love with the land. You don’t think about it analytically. You just take it for granted.”

‘I could feel that CA vibe’

After he earned his PhD, Robbins taught at a series of universities before landing at the University of Arizona, where he helped establish and lead the School of Geography and Development. He left that position to return to his current leadership position at his alma mater. On the university’s website, The Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies is described as a home to “imaginative research that transcends disciplinary boundaries.”

“It’s a huge, sprawling interdisciplinary experiment that’s been going on since 1970,” Robbins says. “You cannot solve the world’s problems with ecology alone. We have everyone from atmospheric scientists to historians, from engineers to authorities on Native American land rights—all looking at ways to meet people’s needs while still protecting the environment.”

This multi-disciplinary approach reminds Robbins of his time at CA.

“What we are doing [at the Nelson Institute] is not that different from what I remember about going to Advanced Physics taught by Pat Hogan,” he says. “We would be studying relativity and end up talking about Oppenheimer and the politics of the atomic bomb. The humanities and the sciences would intersect. That’s what we are doing here.”

Robbins talks about the Nelson Institute as a “small college within a big university,” reprising his experience of finding small groups of like-minded students as friends at CA.

“I know all my students by name,” he says. “We have created a nice neighborhood within a big city.”

With his graduate students, he mimics the style of teaching he had at CA where he had teachers he describes as “mentors.”

“I learned that when people were teaching well—and CA teachers were—they weren’t just teaching stuff,” he says. “They were role models. Once I was supervising graduate students, I could feel that CA vibe. I understood that it’s really important to perform in a way that you want them to emulate so they can succeed.”

‘The freedom to learn on our own’

Robbins remembers his years at CA as a time defined by freedom—for better or for worse.

There was the freedom to do critical thinking in seminar-style classes. He points out that some of his colleagues did not have a seminar class until they got to graduate school, and he had his first one when he was 14.

“At CA, you need to develop your thinking power so you can take what you read, come to a conversation, and have something coherent to say,” he recalls. “That is a lot of responsibility.”

He also remembers the freedom he had at CA with unstructured time, much of which he spent in the Froelicher Theatre, set loose with power tools used in technical theater projects where he got to “build something, and everyone could look at your labor.”

There may have even been a few broken rules in those years—including nights he spent sleeping on the roof of Froelicher.

Although Robbins says it is “both fascinating and troubling” to think that his own six-year-old son might follow in his footsteps, he still values CA’s willingness to let him be the “governor of my own time and sometimes the mis-manager of my own time.”

“We lived in a way that meant learning continued even when no one was telling us what to do,” he says. “CA gave us the freedom to learn on our own, and that is among the most liberating opportunities of my life.”

CA also offered him the opportunity to explore ethical issues. “You were allowed to go out on a limb, look into the future, and think about the world,” he says. “There was an ethical framework at CA that meant you could worry about the world. It was not just a set of skills—it was your responsibility.”

And that brings us back to today—and the challenges presented by a changing climate. Robbins can segue with ease among a host of climate-related topics. He gets your attention when he points out that one-third of bird life has been lost since 1970—that’s three billion birds. But he also remains optimistic when he says, “Our story is about hope.” He believes that human beings have the ability to adapt and change. And since he always keeps in mind his own education at CA, even as he educates the very people who may lead us through challenging times, his optimism is reassuring.