Colorado Academy Fifth Graders put their Design Thinking skills to the test this spring as they worked closely with partner organizations around Denver to help address pressing community needs. The collaborative projects they completed with the Denver Zoo, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Denver Art Museum, Denver Center for the Performing Arts, The Happy Beetle, and Lakewood Parks and Recreation comprised the annual Voices of Change capstone, a months-long culminating experience that asks groups of students to use a broad array of skills and technologies in a project that will make an impact for others.

“Throughout this capstone,” says Grade Five teacher Sara Wachtel, “our students had to use the five stages of the Design Thinking process to take on the challenges facing their community partners. The Fifth Graders had to empathize with users, define the problem, ideate possible solutions, prototype their designs, and finally test and refine their approaches. This was not always a linear process—many students found themselves back at square one multiple times, depending on the feedback they received.”

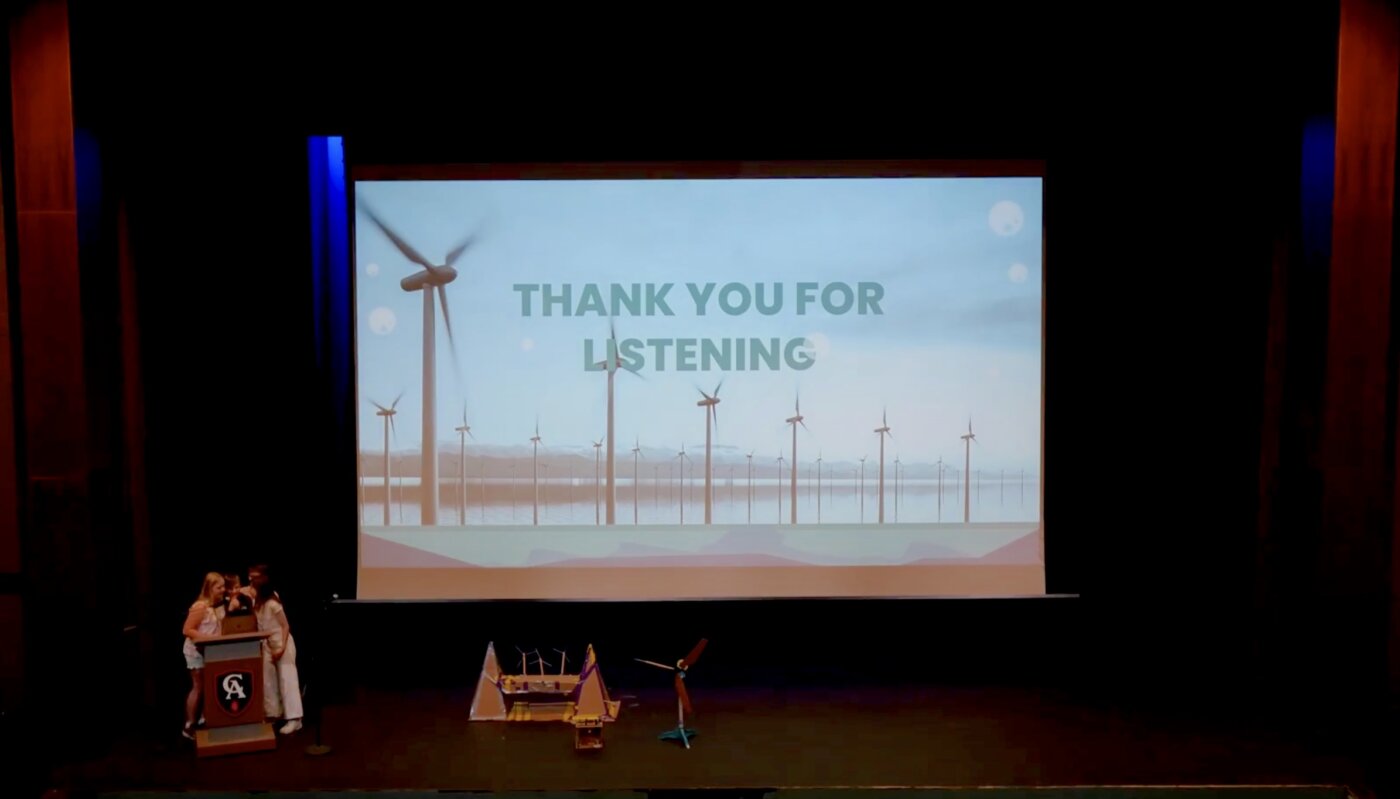

Ultimately, through consultations with their partners as well as outside experts, the students learned valuable lessons, not only about how to solve real-world challenges affecting the environment as well as the organizations themselves, but also about how to be flexible problem solvers and collaborators, willing to accept and act on stakeholder feedback to develop effective solutions. They shared their projects in final presentations given in the Leach Center for the Performing Arts in May.

“When learning has meaning and purpose, students can do anything,” says Fifth Grade teacher Jessica Ohly. “When they believe their work could have an impact on real world problems, they become very excited.”

Denver Zoo

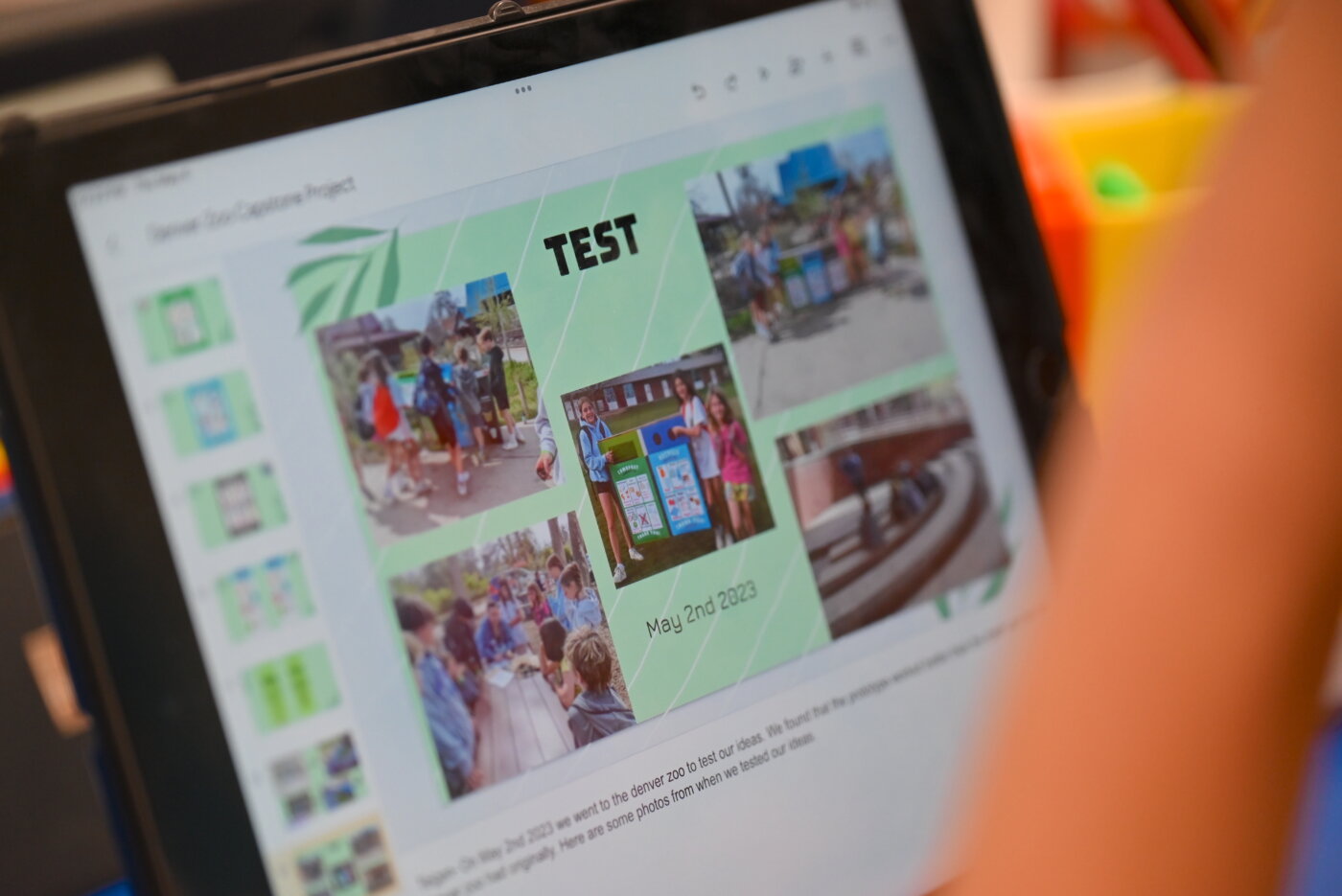

The cohort of Fifth Grade innovators working with the Denver Zoo found themselves facing a tricky problem that Zoo employees had already spent years trying to solve. Speaking with Zoo staff members focused on sustainability and signage, the students learned that too much of the material deposited into the organization’s compost-collection bins was being contaminated with non-compostable items, resulting in higher costs for the Zoo and reducing the impact of their extensive sustainability efforts. The students saw this first-hand when they donned protective gear and used special grippers to complete a “trash audit” by sorting through the compost-only bags, which turned out to contain everything from plastic bottles to cigarettes.

According to Quinn Clarke, “We learned that almost none of the trash items was being disposed of correctly, even though there was already signage on the different bins. It was obvious we had to focus on getting the Zoo guests to think more carefully about what they were throwing away.”

The group pitched several different solutions to the Zoo team, including color coding recyclable and compostable food-service items, redesigning the disposal bins, creating digital instructions accessible via QR code, and more. But, as Teigen Heller explains, “We got a lot of feedback from the Zoo that helped us, and a lot of these ideas didn’t work out in the end.”

Ultimately, the team settled on designing new infographics and lids to more clearly direct guests to the proper receptacle. Working in the digital design app Canva, the Fifth Graders rapidly prototyped numerous signage concepts to go with the lids to make it more likely only compostable items would find their way into the compost-only bins. “We translated our signs into Spanish,” says Rohan Mrig, “and included pictures to make sure everything was kid-friendly as well.”

After fabricating their final prototypes with the help of CA Operations team member Dan Lamont, the students got the approval of Zoo staff to install the new signage and bin covers for a real-world test in May. The results were encouraging: Visitors placed recyclables, compostables, and trash in the correct receptacle 75% of the time, a marked improvement over rates the Zoo had previously been observing. Even better, the students were able to have a conversation with a curious little girl and her mother about their project, making the benefits of this kind of hands-on process crystal clear.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) works to transform energy through research, development, commercialization, and deployment of renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies. For this year’s Fifth Graders, collaborating with the organization’s experts was a chance to think deeply about climate crisis solutions such as wind and solar power.

After meeting with NREL educators and engineers, the students decided to pursue several different projects. Ari Lodha and Arjun Sankar wanted to focus on making solar energy more efficient. They had learned from one expert that even expensive solar panels can be surprisingly inefficient, and they thought they could come up with a way to improve the typical household array. Their solution combined solar panels with a hot water-driven turbine to boost energy production, and the miniature prototype they constructed in Travis Reynolds’ Wonder Workshop was able to generate plenty of power for a tiny family made of corks.

A second NREL team was intrigued with the organization’s work on wind turbines and focused their efforts on envisioning how wind energy could be harnessed at higher altitudes in Colorado’s mountains. They went through a number of design iterations with NREL’s energy experts, proposing and then discarding ideas for special lifting mechanisms and mini-turbines in an array. But then Greta Kennedy suggested a set of turbines on a bridge structure between two peaks. “We thought the wind going through the canyon between the mountains would generate more energy,” she says.

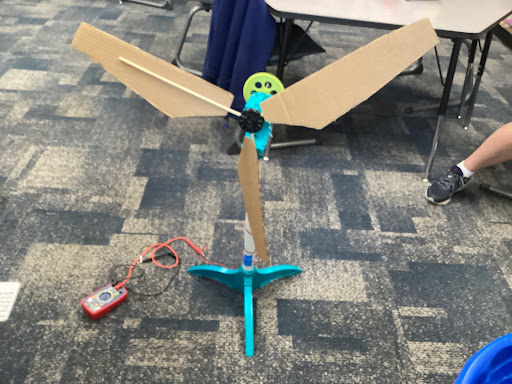

The third and final Fifth Grade team working with NREL decided to devote their efforts to harnessing offshore wind energy. They consulted with Dr. Jacob Ward, an expert on ocean engineering from the University of Maine, and realized that designing offshore turbines and their supporting platforms poses a number of unique challenges, such as high maintenance costs and the need for lightweight materials that can stand up to the ocean environment.

Their initial proposals included ideas such as bamboo construction and turbine arrays, but they eventually settled on a single large turbine supported by a triangular floating platform. “With a huge turbine in the middle, the platform can be more stable and generate more power,” says Gigi Snyder Hanks. Their prototype indeed stood up to the force of a large electric fan when they tested it in a small pool at the Wonder Workshop.

Denver Art Museum

The Fifth Graders who teamed up with the staff of the Denver Art Museum addressed an issue specific to the institution itself: How could it better accommodate and educate the large number of students who visit the museum each year on field trips? The museum had only a small space available to host school groups, which made organizing tours and presenting orientation materials a struggle.

One cohort of Fifth Graders came up with a solution to allow for more efficient organizing of backpacks and water bottles when visitors arrive, which would help get students through the door faster and allow more time for orientation. They also proposed using roped, airport-style lines to divide crowds into smaller and more manageable tour groups.

Another project team turned their attention to the orientation process; as Mackenzie Yi explains, “The Denver Art Museum really wants to make sure no one has a bad visit.” This group thought of a way to make orientations more repeatable so that museum employees could serve more kids. They proposed that the museum record a video of an orientation which could be projected for one set of visitors while an educator gave an in-person talk to another group. “The hardest thing of all was trying to keep our solution simple,” says Lior Korenblat.

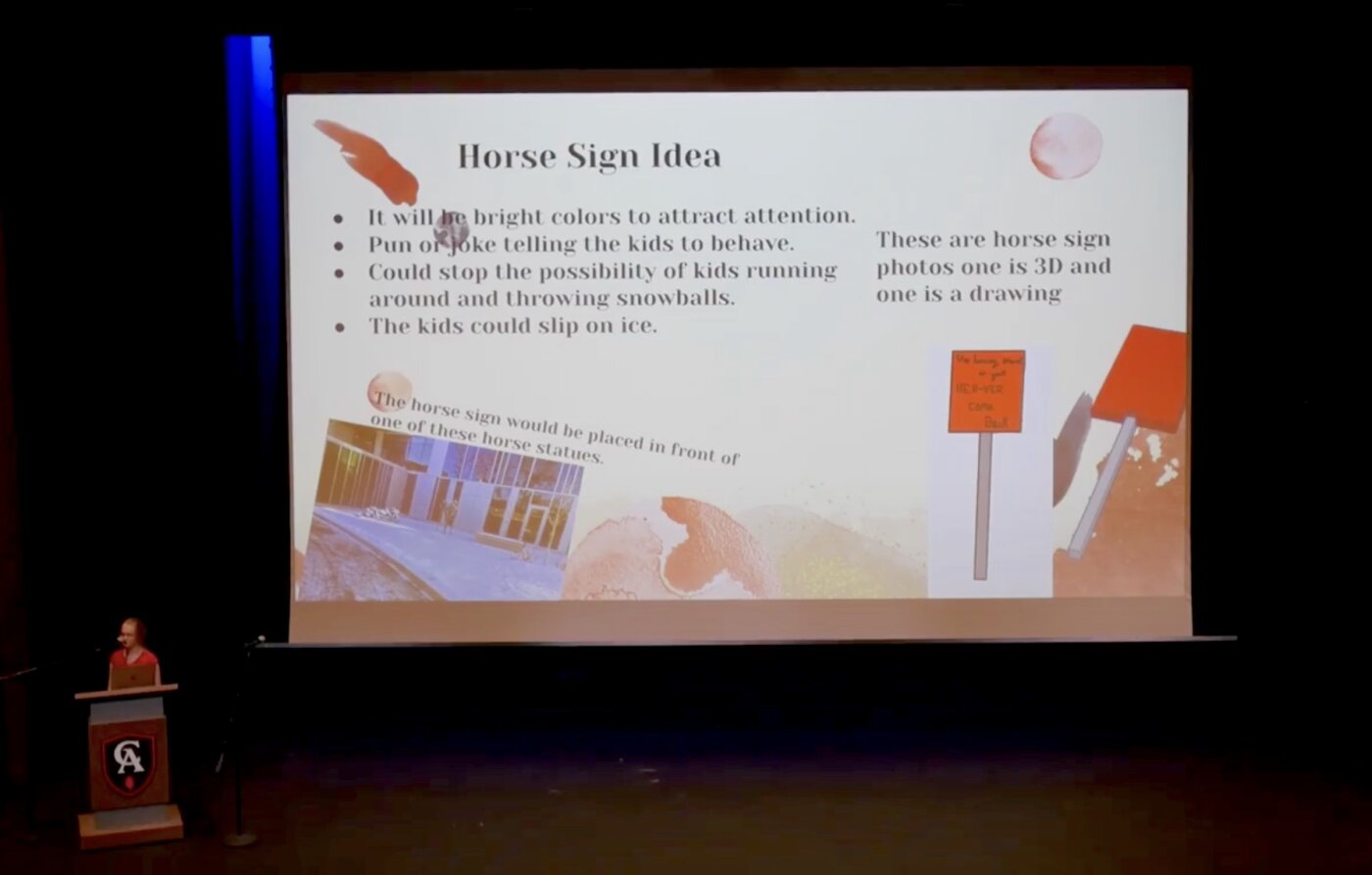

The team also wanted to address a common complaint they heard from museum staff members—unruly student behavior during visits. They envisioned a horse-shaped sign that would feature a warning; Kerra Abar thought the sign should read, “Stop horsing around or you’ll ‘neigh-ver’ come back to the museum again!”

Denver Center for the Performing Arts

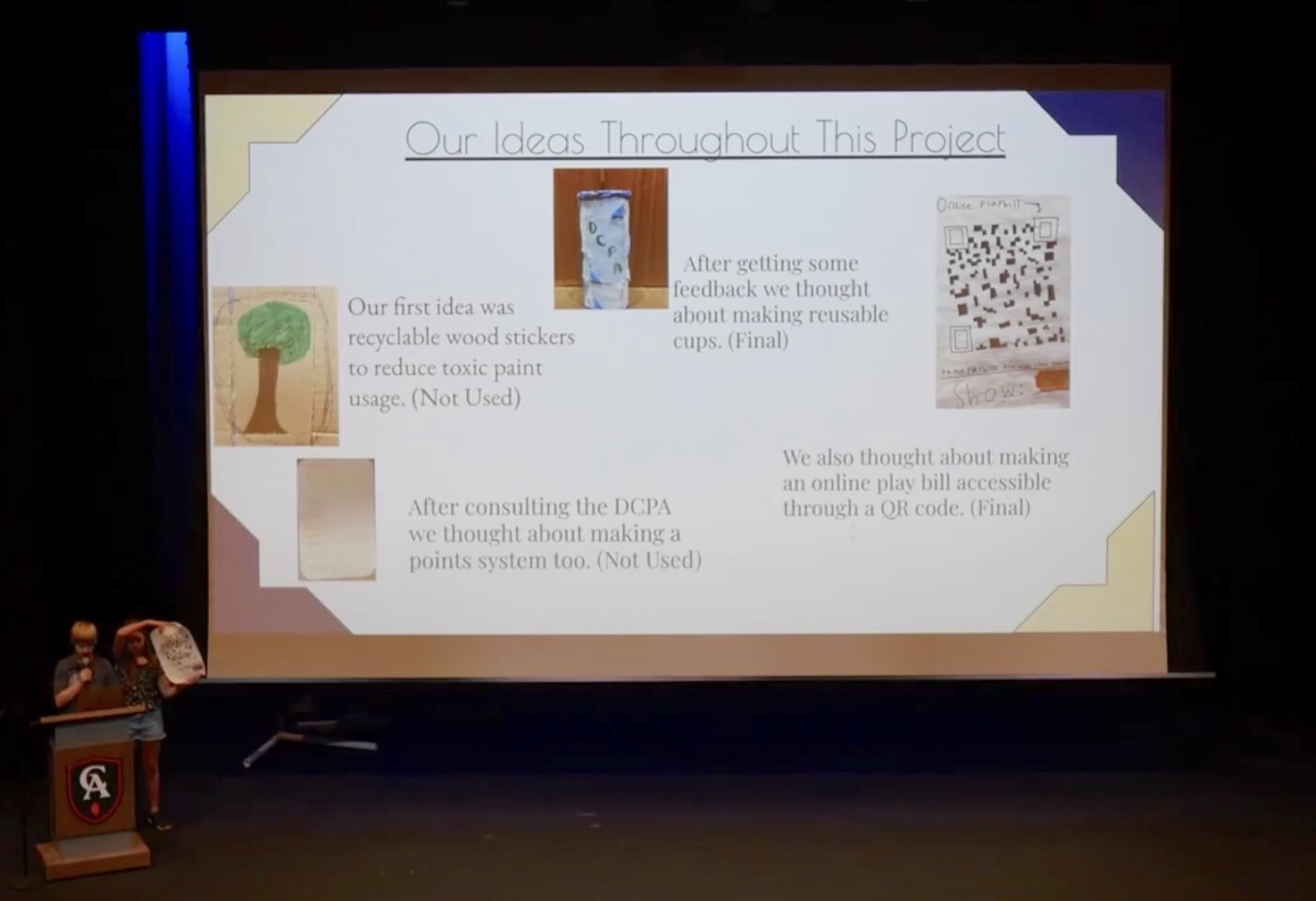

The Denver Center for the Performing Arts (DCPA) posed an interesting challenge to one group of Fifth Graders: How could they make the construction of theater sets more environmentally friendly while increasing the overall environmental sustainability of the organization?

The students were excited to dig into this multifaceted problem. One of their ideas was to help the organization transition to a digital Playbill publication to save paper. Another suggestion was to produce and sell reusable aluminum drink cups that DCPA patrons could fill multiple times over several performances instead of relying on disposable plastic.

Turning to the theater productions themselves, the project team argued that the organization could use more renewable resources to build sets and then be more diligent in carefully disassembling and reusing materials at the end of each show. They also suggested that DCPA could partner with local thrift organizations to source costumes and props.

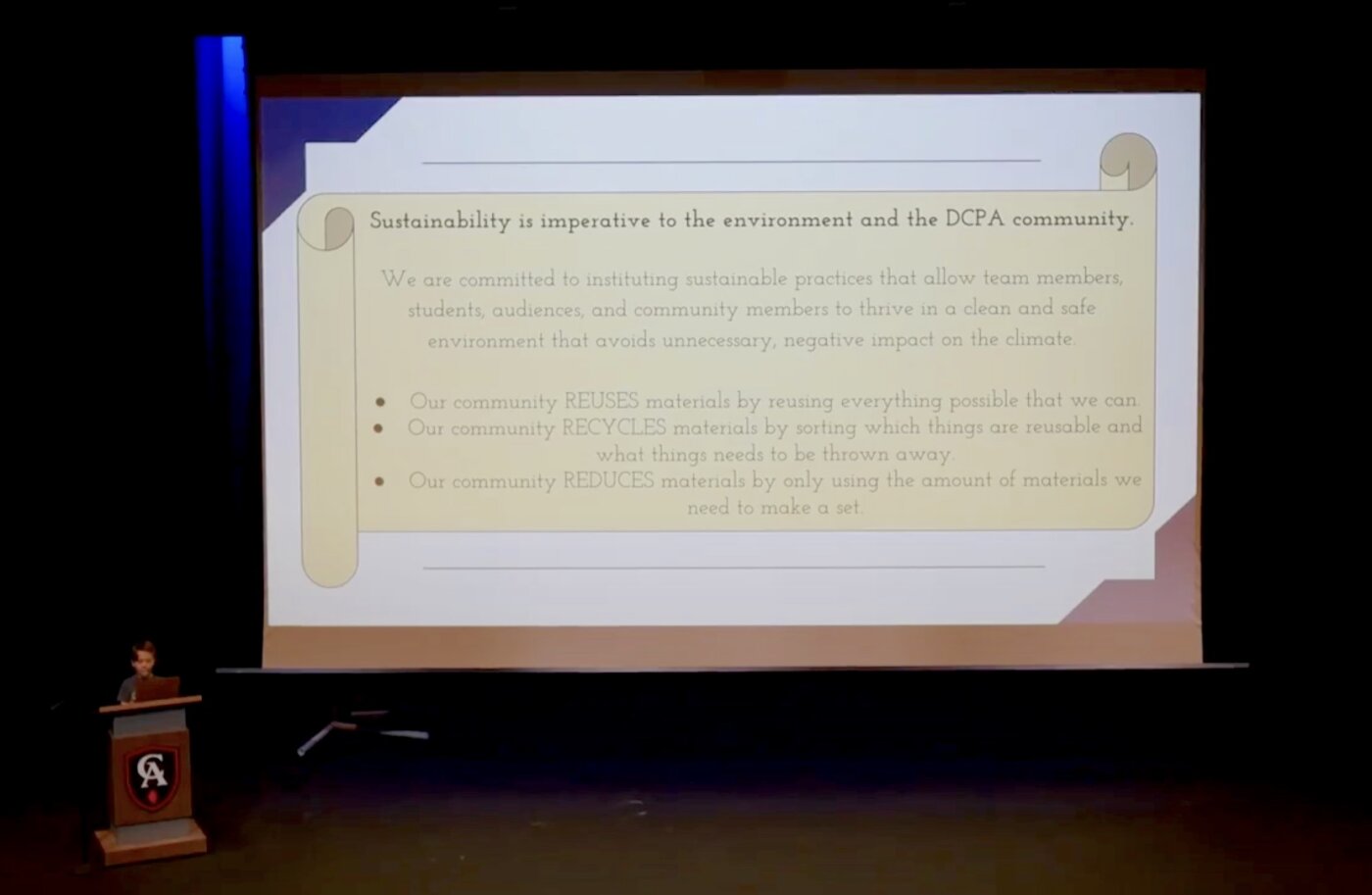

These Fifth Graders also came up with innovative ways that strategic communications could contribute to meeting DCPA’s goals. They were justifiably proud of a sustainability “commitment statement” they drafted for the organization, which begins, “Sustainability is imperative for the environment and the DCPA community.” “This is a lot like how CA’s mission statement promises to create ‘curious, kind, courageous, and adventurous learners and leaders,’” explains Vira Loya. The statement even pledged to support a summer program for young people that would offer a theater experience as well as sustainability education.

The Happy Beetle

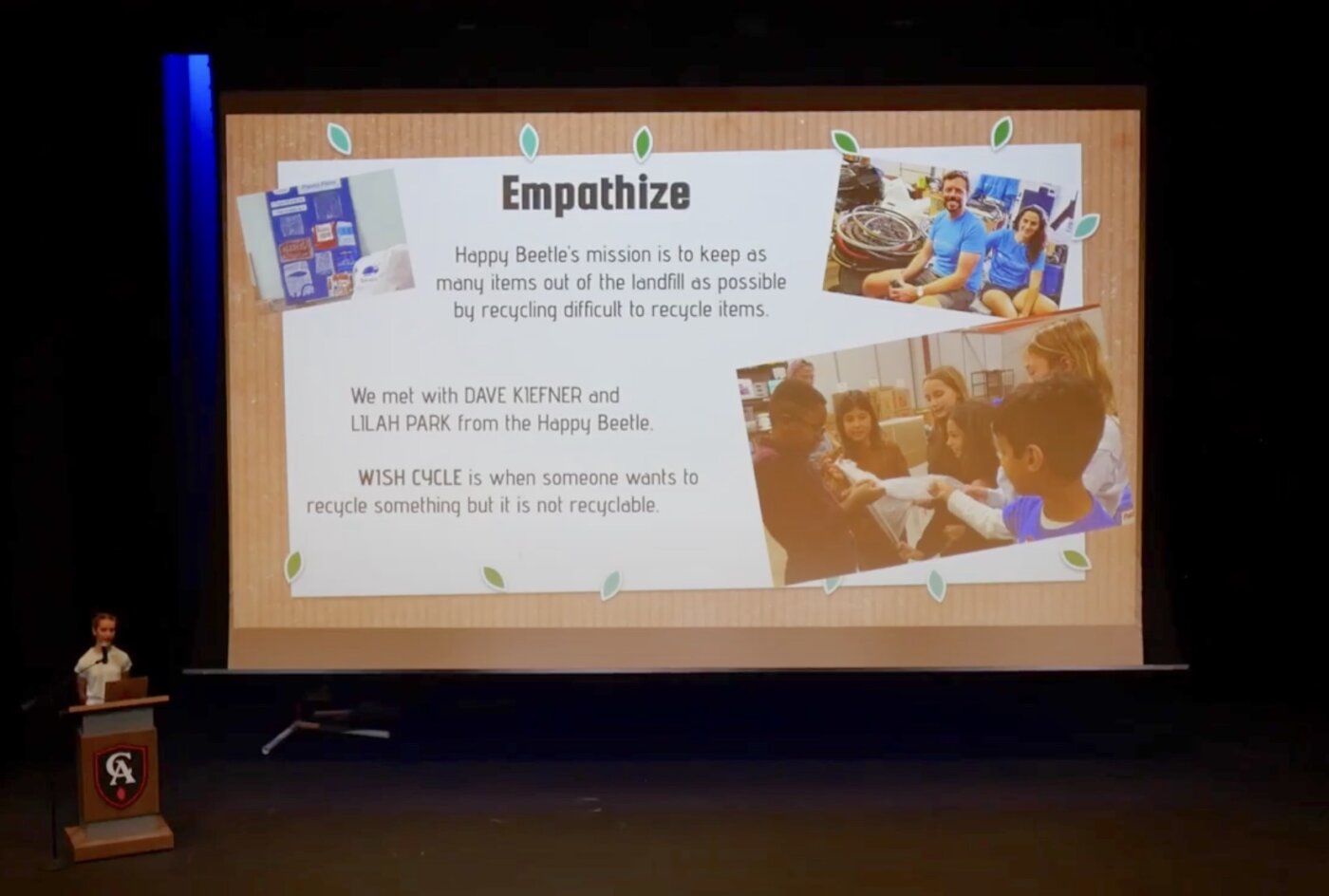

Fifth Graders were intrigued with the mission of The Happy Beetle, a door-to-door pick-up service for hard-to-recycle items that can’t go into curbside bins. They met with the organization’s founder, Dave Kiefner, and recycling specialist Lilah Park to discuss ways The Happy Beetle might expand its services to more schools and businesses, while addressing the persistent challenge of contamination, which makes recycling items like plastic bags much more difficult.

“We brainstormed a lot of different solutions to this problem,” recounts Naqiya Rodriguez. Among the team’s strongest ideas were a specialized scrubber to help customers clean plastic bags and other materials headed for recycling, and a catchy song with lyrics that encouraged proper preparation of hard-to-recycle items.

The students also created an educational book about recycling that would encourage children to take advantage of Happy Beetle receptacles placed around schools. The book is aimed at preventing “wish recycling,” which, as George Bruno explains, is “when you ‘wish’ that something that should go to a landfill—such as a dirty plastic bag—could be recycled, and you put it in the recycling bin, contaminating everything else.” The book, which presents illustrations of how to properly recycle that even the youngest students can understand, received positive reviews from The Happy Beetle as well as a test group of CA Second Graders.

Lakewood Parks and Recreation

The final Voices of Change cohort, who became part of a story produced by Colorado Public Radio, worked closely with Lakewood Parks and Recreation officials on an emerging environmental threat. As Matthew Oram describes the key facts they learned from bee specialist Carmen Weiland, “Our food supply and environment depend on pollinators such as bees, and yet bees are dying at rapid rates due to varroa mites.” The mites are a global problem; they invade and feed on honeybee colonies and ultimately destroy them.

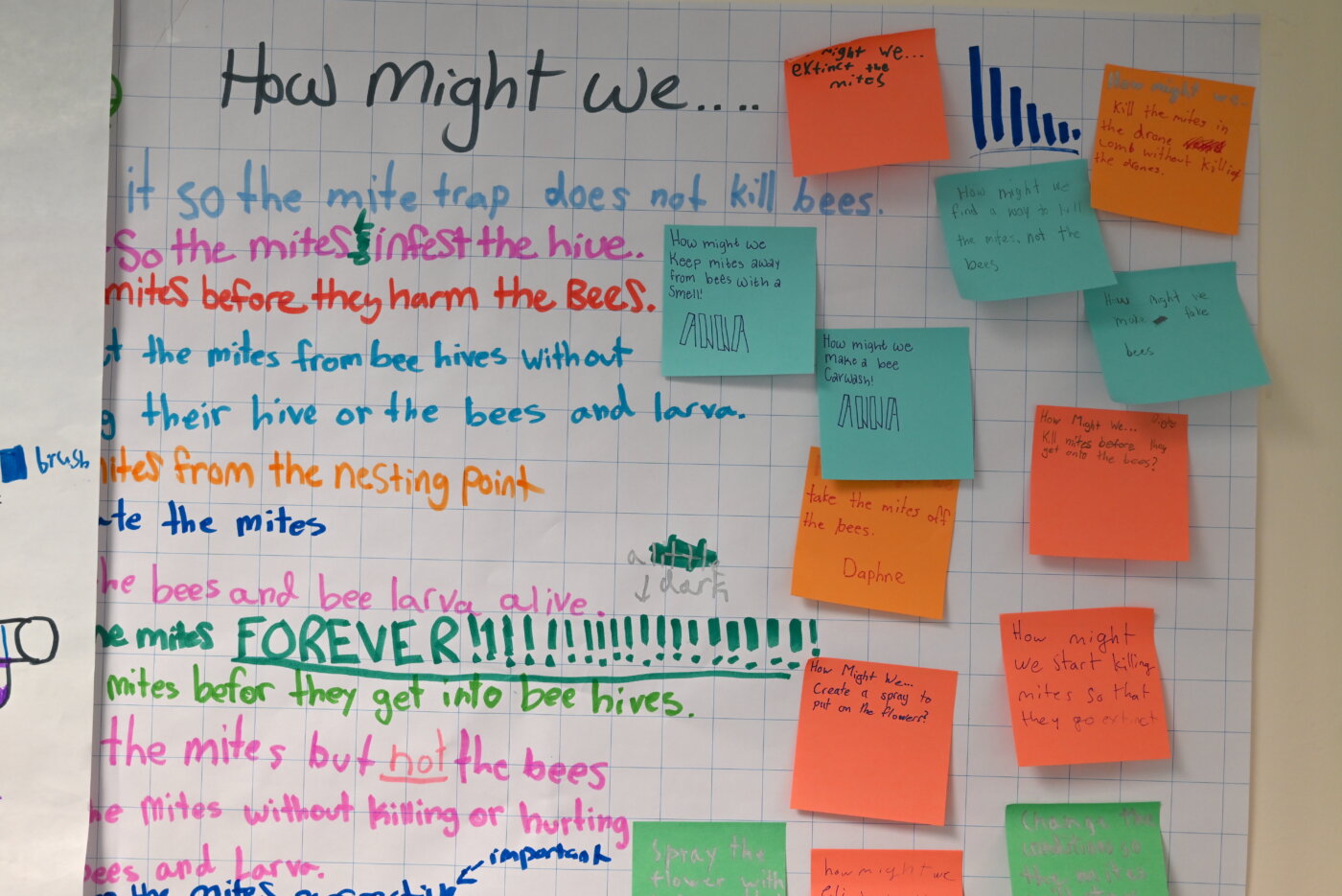

The students’ mission, according to Lakewood Parks Ranger Dave Ford: Devise a way to prevent mites from attacking local beehives without using chemicals that could harm the bees, humans, or wildlife. It was no easy assignment, with beekeepers around the world already working on various solutions to the critical problem.

The Fifth Graders quickly zeroed in on the concept of a fly-through bee cleaner that could take advantage of the PVC piping that Lakewood had already installed at the entrances to their hives. The students wanted a way for the mites to be removed when the bees flew through the pipe. They learned from the experts that the honeybees were strongly attracted to lavender and thyme, so they included that fragrant combination in their cleaner designs to draw in the bees.

The tricky part was getting the mites to fall off into the water-filled container or trap they planned to build into the pipe. One team of innovators suggested bristly brushes that could scrape off the mites, but these were deemed too rough for the bees. Reflecting on the question “How might we…?” that guided the Fifth Grade throughout their capstone work, another group asked, “How might we move the mites?”

The surprising answer, suggested by bee expert Weiland, was powdered sugar. Students learned that powdered sugar is often used to coat honeybees to make identifying the mites easier, and they wondered if it could also be used to protect the bees. Experimenting with battery-operated fans connected to the PVC tubing, the students found they could dust the bees passing through by blowing sugar at them. The sugar coating would make it harder for any mites to attach themselves to the bees, and even better, it would encourage bees to groom each other and potentially remove any mites that were already attached.

“By encouraging innovation and problem-solving around a local, contemporary problem,” says Wonder Workshop teacher Travis Reynolds, “the capstone is really a wonderful opportunity for Fifth Grade students to synthesize and demonstrate all of the skills that they’ve learned throughout their time in the Lower School.”

Read more about the Lakewood Parks and Recreation bee-cleaning project at Colorado Public Radio.