Well, if that title didn’t get you to click this link, I don’t know what will!

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the function of schools and the role education plays in society. In particular, I’ve been thinking about the conundrum kids face in schools in terms of their mindset when approaching teaching and learning. The author Amy Tan has a great quote: “It’s both rebellion and conformity that attack you with success.”

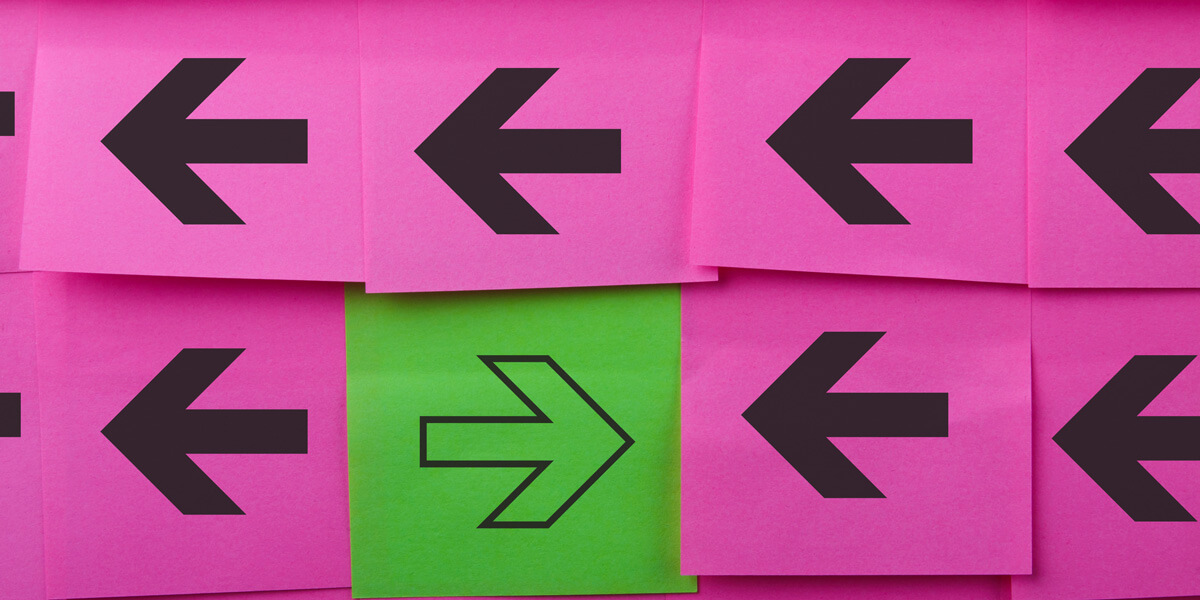

The nature of formal education actually creates a fundamental dilemma for students. They can be rewarded by “playing the game” of school. By following the rules and norms of doing their homework, they will get ahead. Often, they will graduate with distinction and find themselves at a great college and university, but they also can be rewarded when they break tradition and become bold leaders and thinkers.

A more disruptive approach to learning can create all kinds of net positives for students, even if it causes some short-term conflict. The key is having a school program that allows for kids to do a bit of both—understanding how to study in a formal educational program and also learning how to step out and take charge of their learning.

Creating schools for an industrial economy

In the United States, formal education for young people has existed as way to propel the Republic—to create well-informed citizens who take part in this great experiment in democracy. Schools were also developed to fuel the economy—to create skilled workers. It is not coincidental that many school districts throughout the nation have dramatically cut arts and music funding, while increasing resources for STEM education. (Such reallocations would seem to make superficial sense, but they overlook the key role creativity plays in driving our economy and the close relationship between design and innovation.)

As I have related many times before, the basic structure of modern schools was modeled on what was needed for the industrial economy of the 20th century. In fact, there are still far too many private and public schools that maintain this “industrial” approach to teaching and learning: Teachers dispense content to large classes of students organized neatly in rows. There is also a role that formal school plays in helping socialize young people. Students are taught how to work and get along with others. They learn which behaviors are socially acceptable and which are not. Ultimately, these rationales create pressures on students to conform in a variety of ways. Some of this is good, but some of this pressure limits student potential and individuality. This conformity is achieved because most students realize it is fully in their interest to do so. Adults can probably all remember some incident from their youth when they learned it was better not to question a situation or talk back to an adult with whom they had a disagreement or raise a question in class that might completely derail a teacher’s line of argument. American schools have enforced a type of conformity through discipline.

Some examples—such as efforts by so-called educational “reformers” to assimilate Native American children in the 19th and early 20th century—stand out as the most egregious. (American Indian schools would force children to cut their long hair, force them to adopt English names, and physically punish them for using their native languages.) Thankfully, modern schools don’t go that far, but there is an expectation that students will always be deferential to authority. Humans are typically very adept at finding the path of the least resistance. Putting one’s self out there always carries risks. If we think about the biological determinism that drives some adolescent behavior, it’s actually quite amazing that any child will find ways to stand out and not conform to the pressures placed on him or her by society.

Bold and independent learning at CA

I like to encourage bold and independent thinking. As a faculty member at Colorado Academy, I know I am not alone in this type of thinking. I love it when a student asks me some hard question that challenges me to think about why we study a particular subject or why we have structured our program in some way. It’s always good to reexamine one’s assumptions and values.

On The Atlantic’s website, you can find a great animated talk by Francesca Gino of the Harvard Business School, entitled “Why Your Kid Should be a Rebel.” https://www.theatlantic.com/video/index/567976/home-school-5-rebels/ Her talk is not giving license to excuse nihilistic and destructive behavior by students. Rather, she talks about the healthy role questioning can have for young people.

I feel so lucky that I get to spend at least part of every day considering what the world looks like through a child’s eyes. Think about how a Kindergartener or First Grade student or a Ninth Grade student sees the world. Think of the things they are asked to do, often with no explanation of why they need to perform a task a certain way or take part in a particular activity. The questions abound: “Why do I have to study computer science or foreign language or history?” “What’s the point of this particular class?” “Why I am required to take a sport or art class?” “Why can’t I tackle my friend in the hallway?” Of course, the adults have really good answers, but explanations sometimes aren’t enough.

“Why?”

The thing I love about visiting CA classrooms is hearing how often the word “Why?” is asked both of students and by students. Our job is to help kids understand the world and to encourage a little rebellion along the way. One great example of healthy rebellion in schools comes from Bill Gates. He writes, “In Ninth Grade, I came up with a new form of rebellion. I hadn’t been getting good grades, but I decided to get all A’s without taking a book home. I didn’t go to math class, because I knew enough and had read ahead, and I placed within the top 10 people in the nation on an aptitude exam.” Of course, Gates is a unique person, but there are other examples like him here at CA.

I love our new Upper School newspaper, The Student Review, which was set up by students, not to report the news per se, but to have a forum to discuss issues related to institutional change. Another example of “out-of-the-box” thinking originated with our faculty in the creation of REDI Lab. Our faculty members created this program for Juniors with the assumption that students—not teachers—can actually drive successful learning. In this newsletter, you can read about an example of what happened in REDI Lab when Ellie Bain decided to replicate classic works of art with a modern twist, highlighting disruptive actions. These examples—and the many additional times students have come to me, an advisor, or other school leader to pursue some type of program that’s off the beaten path—demonstrate how CA welcomes acts of creative revolution.

So, as we enter the new year, I hope we can have a bit of positive disruption to make our learning community even stronger.