When Jenny Leger was hired to lead the preschool program at Colorado Academy in 1995, she had no idea that just a few years later she’d also be in charge of the first West-of-the-Mississippi affiliate of Horizons, a fledgling model for educational equity originally developed at New Canaan Country School, an independent day school in New Canaan, Conn., in the 1960s.

“I had never even heard of Horizons until I came to CA,” Leger recounts.

In New Canaan, under longtime Executive Director Lyn McNaught, Horizons offered a six-week summer program for students from surrounding public schools, who received academic support, sports and field trip opportunities, and swimming lessons. The design of the program was based on the work of Dr. Edward Zigler, at the time a professor of psychology and the Director of the Child Study Center at Yale University. Zigler is credited with creating Head Start, the federally funded service that bolsters early learning and development, health, and family well-being for eligible children.

After decades of successful outcomes in Connecticut, McNaught and a group of Horizons champions established the national organization the same year Leger came to CA, with the goal of expanding the successful New Canaan model to other communities. Three years later, in 1998, then-Head of School Chris Babbs took a chance on bringing the program west to CA.

“When I first stepped into the role of head,” Babbs recalls, “part of my mandate from the Board of Trustees was to engender greater community involvement for the school. That was a time when community service and activism were really becoming part of our mission, and the idea was to get us out of the cloistered existence that sometimes independent schools maintain.”

Babbs observes that the boarding model under which CA operated through the first 60 or 70 years of its existence had begun fading away under the leadership of his predecessors, F. Charles Froelicher and Frank Wallace, and that when Babbs came onto the scene as head in 1991, the school was entering a new phase. The size of the student body would nearly double from 500-some to over 900 by the end of his tenure in 2008, and wider swaths of the Denver Metro area would access the campus than ever before.

Prioritizing openness and diversity during this time of change, argues Babbs, obviously meant undertaking new initiatives to bolster funding for financial aid and enhance recruitment efforts. But it also took the form of deliberately reaching beyond the suburban campus in other ways, seeking partnerships with schools and nonprofits to deepen CA’s connections throughout Denver and broaden the overall experience that was reflected within the school community.

That’s why, while attending a workshop at the National Association of Independent Schools annual conference in 1997, Babbs was struck with the Horizons approach. The program’s public school-focused pre-K–12 model felt like a perfect fit for CA.

“Zigler understood that the summer learning gap, or ‘summer slide,’ was actually doing real harm to those kids who didn’t have the advantages of families like those who send their children to CA,” Babbs explains. “And he believed you could address that by bringing in real classroom teachers to run a robust summer enrichment program for these kids, and by having them return year after year.”

According to Zigler’s blueprint, all Horizons programs begin with a single class of children who have just finished public Kindergarten; most should be performing below grade level, believed Zigler. Then, when those students return the following summer at the end of their first grade school year, another class of Kindergartners is enrolled. The program grows organically, grade by grade and year by year, ensuring the development of long-term relationships with students and their families.

Though he knew he wanted to bring Horizons to CA, Babbs still needed a public school partner to make the program work. On paper, CA was well positioned to attract students from Denver’s bilingual west side who could benefit from summer academic and enrichment opportunities. So Babbs began cold-calling schools in these neighborhoods, and found a willing partner in Knapp Elementary, whose then-principal, Katherine Adolph, was eager for her pre-K-5 school, which served mostly Hispanic and Latino children eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, to be CA’s first Horizons “feeder” school. It’s a role it continues to serve to this day.

Leger, an experienced early childhood educator, was the ideal candidate to lead the experiment, taking over from the late Sean Smith, the Middle School Principal who had worked with Babbs to get the program up and running with the approval of the Board of Trustees. Initially brought on as the first Horizons Kindergarten teacher at CA, Leger found herself in charge of the program’s rollout when Smith’s other duties as a dean and coach pulled him away.

“One day, Sean just said to me, ‘Take it from here, Jenny,’ and I immediately had so many questions,” recounts Leger. “It’s very different today with Horizons National providing all kinds of guidance to local sites, but at the time, the organization was still very young, and there was no formal curriculum or plan for activities. I had to do what I thought would be best. And I did.”

Innovation required

Leger’s background as an educator made it immediately clear to her that the first cohort of Horizons Kindergarten students from Knapp, many of whom didn’t yet know the alphabet, needed direct literacy instruction along with the enrichment activities such as arts and crafts, swimming, and sports that were more typical of Horizons programs on the East Coast. So she built a hands-on, project-based classroom curriculum that gave children the fundamentals they’d need to succeed when they went to first grade in the fall.

“If they’re going to be successful, kids need to be reading after the first three years of their education,” Leger asserts. “Because after that, they’re reading to learn. If they can’t read by the end of those first three years, they fall further and further behind.”

The program Leger designed incorporated small-group instruction, much like in the early grades at CA, led by volunteers, interns, and assistant teachers who could offer one-on-one attention. A handful of high-achieving students, specially chosen to participate in the program, would work alongside their peers who needed more support, modeling success in the classroom.

Leger’s program offered breakfast and lunch, vitally important for students who often were experiencing food insecurity at home. Eventually, Leger brought in a reading specialist, CA parent and nationally recognized educator Judy Dodson, who designed curriculum and trained teachers.

Most importantly, Leger slowly built up trust with the west Denver families who were sending their children to Horizons on CA buses.

“We did a lot of talking in the beginning,” she remembers. “We had to assure parents that we’d take good care of their children. We had to let them know that CA was a place their child would be safe, nurtured, taught, fed, and provided enriching experiences like swimming. I’m so proud of the work we did with Katherine Adolph at Knapp—a fluent Spanish-speaker—to make this such an authentic opportunity for that community.” From initial skepticism, Horizons ended up with a waiting list.

The inaugural summer was in full swing when Leger received a visit from the legendary McNaught, who wanted to see how CA was implementing her program. After a day spent observing children learning and playing, she met with Leger and told her, “Jenny, you’re not doing Horizons as we’ve always done Horizons. This is very different.”

Admits Leger, “All I was thinking was, ‘Oh no, I’ve failed.’” But McNaught surprised her by explaining, “Horizons has always been camp-like, with lots of activities like arts and crafts. We read to the children, of course—but you’re actually teaching your students to read. And from everything I’ve seen, it’s working. The kids are with you.”

From that moment, there was no looking back, and Leger continued to innovate as Horizons at Colorado Academy, as it was now called, grew and thrived. By the early 2000s, the program had expanded all the way to the eighth grade, and the national organization was looking to CA’s implementation as a model as it continued to launch new sites throughout the country.

According to Lorna Smith, the CEO of Horizons National, organic local innovation like that taking place at CA was key to shaping the organization’s national vision. “Jenny Leger and Chris Babbs played a large role in helping us to co-create the future of Horizons,” she says.

In 2005, Smith, then the assistant to the national director, came to Colorado for a regular site visit. When she saw the continued success of Leger’s reading-heavy curriculum model, she knew it was something special.

“‘This is remarkable, what’s happening here,’” Leger recalls Smith saying, “’and it’s not happening in other places. But I’m beginning to think it should if it can be done with the same amount of joy and spontaneity.’”

“Not long after that visit to CA,” recounts Smith, “we brought all of the local affiliates together in a room to decide what is really at the heart of Horizons.” Now CEO of a network of fewer than 20 Horizons sites nationwide, Smith wanted a clear plan in place for driving the nonprofit’s national expansion.

“That experience of working together with CA and the other affiliates to determine what is core to our program really provided the foundation of what Horizons is today,” Smith attests.

Diving in

At the more than 70 affiliate sites in 20 states that today comprise the national network, serving nearly 7,000 students annually, perhaps nothing is more central to the Horizons experience than swimming lessons, a signature element of all Horizons programs. Zigler had insisted on the importance of learning to swim when initially working with New Canaan Country School to create its model. The confidence boost it provided was critical in building social-emotional foundations for lifelong success, he argued.

Lucky for CA, the large, Pre-K–12 campus was one of the few early sites to have its own pool, and swimming has been a centerpiece of its Horizons program since the very beginning—a constant that has made a positive impact for hundreds of students throughout the program’s 25 years.

Jose Martinez, an alumnus of Horizons at CA and currently Dean of Students at Knapp Elementary, believes that learning to swim in CA’s pool helped to change the trajectory of his life. Now the summer Director of Operations, Henning Health & Wellness Director, and Restorative Justice Counselor with Horizons in addition to his role supporting students during the school year at Knapp, Martinez says that when he first was enrolled in Horizons as a Kindergartner in the program’s second year at CA, he was timid and shy.

“As a student, I wondered why teachers were making me do all these things that I didn’t want to do or didn’t understand,” he says. But learning to swim during the summer at Horizons, he explains, opened him up to taking risks and facing challenges that might seem intimidating.

“Being able to jump in the pool sets you up to be an advocate for yourself, to cope with obstacles, to find the belief that you can overcome whatever you might encounter in life,” says Martinez. “And now in my role at Knapp, I have a natural connection to those kids who are struggling. I can tell them, here are the things I struggled with before Horizons, and I overcame them. Having that confidence in yourself affects your academics—everything. That’s why I love what I do, and why I’m excited to do that every summer at Horizons.”

Martinez’s path—from Horizons to his role at Knapp and now back to Horizons—is far from atypical, according to the current Executive Director at CA, Daniela Meltzer. In her five years with the program, she’s seen numerous alumni, like Martinez, return to campus to pass on the lessons they learned.

“So many have gotten so much out of the program,” according to Meltzer, “and they want to give that to the next generation. What’s even more profound is when those younger students see that the leaders, teachers, interns, and volunteers in the program were once just like them—they can start to envision themselves one day doing the same thing. It makes a huge difference for them to see models of success.”

Indeed, the Horizons program at CA is staffed predominantly by its graduates. Another longtime volunteer and staff member, Jessica Nuñez-Hernandez, is an alumna of the program who started in third grade after being diagnosed with dyslexia. She went on to intern and assistant-teach with Horizons, and after earning her teaching certificate, returned as the lead pre-K instructor. She is now the Program Director, working side by side with Meltzer.

“My Horizons third grade teacher really pushed us to conquer challenges like the swimming pool,” she says. “I did the same thing when I was a teacher—it gives students a sense of confidence that, if they can do this one thing that scares them, they can do anything. They can conquer bigger fears, like reading or math.”

That growth—the confidence inspired by constant support and encouragement from a close-knit community—is often described as “Horizons magic,” says Meltzer.

“The relationships that Horizons creates—and they are year-round, because so many of our teachers and volunteers are also involved at Knapp and live in the community—give our students the tools they need to surpass the challenges they face and to do whatever it is that is meaningful to them.”

Yatzari Venzor, a Horizons alumna who is also a member of CA’s Class of 2019, agrees. Her mother, Nelly Fernandez, CA’s Assistant Custodial Supervisor, learned about Horizons from Leger, and Venzor was enrolled from third to eighth grade. When she was accepted to CA as a Fourth Grader and found herself daunted at the prospect, she says, “Even before I really understood what I was getting myself into, Horizons had prepped me for school: getting used to doing work, completing assignments—those very basic things you need to build a foundation to be a good student.”

When she continued on to Middle School, because of her ongoing Horizons experience, Venzor knew all about how to use the hallway lockers that confused her classmates. And by the time she reached the Upper School, she was becoming involved in issues of equity and inclusion, leading the Faces of Diversity club and conducting a PlatFORUM workshop for her Senior-year capstone project. She was a Horizons volunteer, intern, and assistant teacher, and went on to earn her undergraduate degree in Communication Sciences and Disorders at the College of Wooster.

None of this, she insists, would have happened without Horizons.

“I have met so many amazing people and had so many amazing opportunities because of the program,” Venzor says. “And now, being on the other side and having had the opportunity to connect with so many students as a teacher, I think I realize these kids are so special. I feel like maybe they’re overlooked a lot of times just because of where they come from.”

Meeting new needs

As the number of Horizons alumni making a difference has continued to multiply over the past two decades, so, too, have the needs of those children Horizons serves both nationally and locally. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this into stark relief, as it became clear that students living near the poverty line were profoundly affected by learning loss.

Head of School Dr. Mike Davis saw that time as an opportunity for CA to deepen its collaboration with Horizons, and worked with Meltzer to implement a year-round tutoring program. Starting with online sessions, the initiative went in-person in 2021, with Upper Schoolers traveling to Knapp Elementary twice a week for one-on-one time with young students.

“When we had to respond to COVID,” says Davis, “we realized that we as an institution could turn on a dime, being flexible and innovative to meet the needs of our community. And we also saw that so many kids and families nearby were hurting and falling further behind. We knew we had to leverage every resource at our disposal to help those in the larger Denver area, and Horizons was central to that effort.”

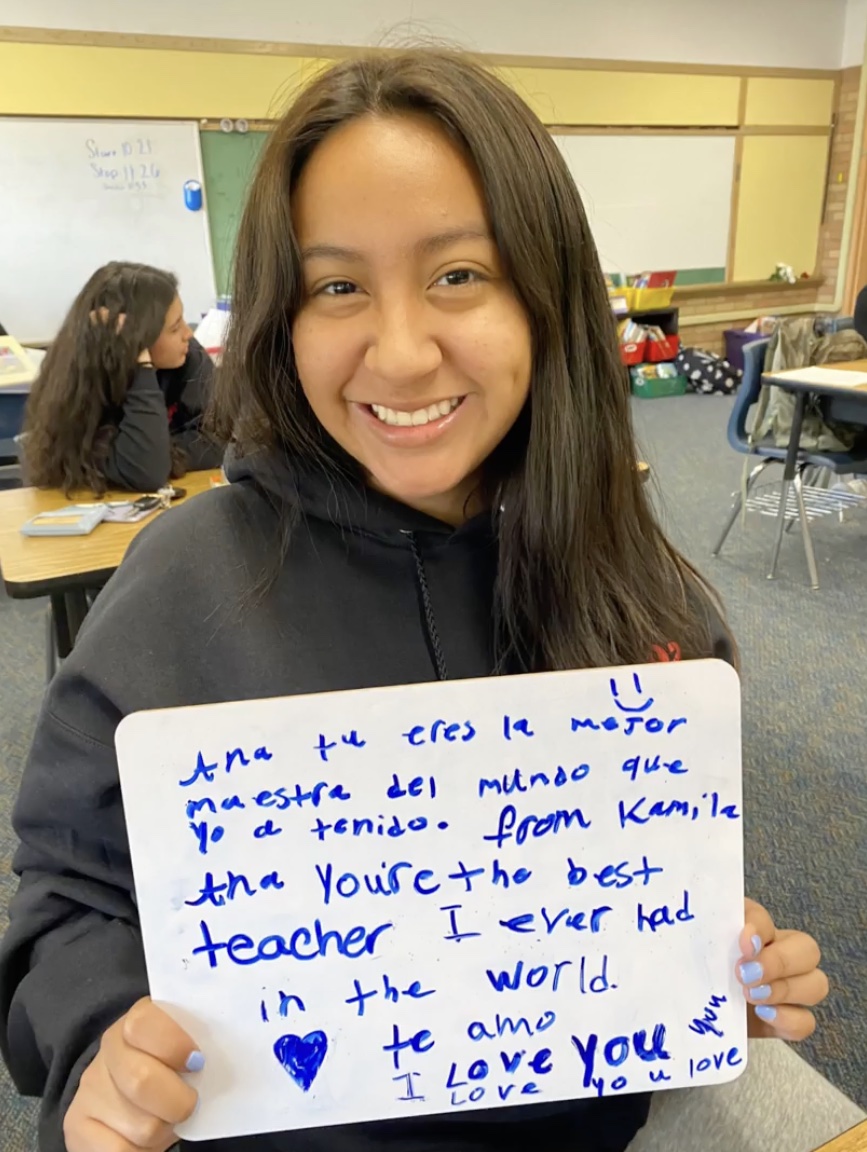

The tutoring program now brings help with homework, fun and games, and meaningful connections to more than 30 students each year. It’s an initiative that has had almost as many benefits for CA as it has for the Horizons students. CA Senior and Horizons volunteer Ana Yáñez worked closely with Kamila, a Knapp third grader. Silly, hardworking, and loving, Kamila would write Yáñez a special note in Spanish or English on a whiteboard each week, and Yáñez, who attended a public school much like Knapp through eighth grade, explains that Kamila reminded her of herself.

“I was the one tutoring Kamila,” she says, “but I feel as if the impact we have had on each other is greater than I could have imagined. While not always as eager to do her math homework as she was to play Simon Says, Kamila has helped me unlock different sides of myself. She has taught me about responsibility and hard work.”

With the addition of the tutoring program, Horizons now serves well over 200 students a year both on and off campus. From an offering that began with a single class of Kindergartners and a fundraising approach that relied on Leger and the generosity of a handful of CA parents, Horizons has grown into an $800,000 annual operation serving children from pre-K to twelfth grade, with more than 60 summer staff members and volunteers and the support of hundreds of CA families.

There’s even a new Horizons garden program, begun in 2022 when Catherine Rollhaus and Julie Martin, co-chairs of the Executive Board, planted the seed of the idea with Davis. CA students and Horizons participants—along with numerous Horizons board members and volunteers—worked together to construct raised beds, plant seedlings, and create artistic stepping stones to decorate a plot on campus. Says Rollhaus, “I just love the idea that we are able to use this beautiful campus to educate and engage children that might not otherwise have access to this kind of space.”

“The success of this program has really shown how much the CA community is invested in making an impact more broadly in Denver,” Meltzer observes. “Virtually all of our funding comes from CA families. They’re volunteering during the summer or during the school year on our ‘Super Saturdays,’ when we invite Horizons students and their families to campus just to stay connected with them. Some are tutoring, or attending our annual Wine & Dine fundraiser, or serving on our board.”

With that kind of buy-in, Meltzer has been advocating for further growth, starting with a 2023 name change to Horizons Colorado. The new moniker points to her ambitions, along with Davis’s, of reaching even more students.

“How amazing would it be if we could get five or ten percent of all Denver Public Schools students enrolled in Horizons?” she wonders. In part, that work has already begun, with Meltzer reimagining the small Horizons high school-age program to connect older students with mentors—most of them Horizons graduates—who can offer support through college and beyond.

“Schools like Colorado Academy need to do our part to make our community better,” adds Davis. “We care deeply about society; we care deeply about creating leaders who are going to make change. We wish we had unlimited resources to educate more kids. But through Horizons, we have a chance to make a start.”

According to Lorna Smith, the need for programs like Horizons has never been greater, and the national organization’s latest strategic plan calls for reaching more youth all across the country—including in Colorado.

“We are incredibly excited and grateful at Horizons National for the leadership of Mike and Daniela, along with the CA and Horizons boards, in envisioning growth throughout the whole state. I can tell you that when I asked them if Denver wasn’t enough of a challenge, CA was very clear that they wanted to cast a wider net.”

“That’s one of the things that is at the heart of Horizons’ growth as a national organization,” Smith continues. “We have such a deep respect for local ownership and the wisdom of people in their own communities. It’s not for us to say how best for you to work; it’s for us to listen and support. And the clarity and enthusiasm of the team at CA are a testament to that approach.”

As Leger explains it, Horizons Colorado, as it is now called, proves CA is willing to “walk the talk” of equity and inclusion. In her first years running the program, she insisted on taking her young Horizons students on tours of the CA campus, talking to them about its history and especially about the many sculpture installations, about which they were particularly curious.

“Many of them just had no concept of sculpture—they came from places where that wasn’t something in the environment,” recounts Leger. “But once they learned about works like the Stone Book and Robert Frost, they began to feel a sense of ownership, as if CA was their school, not just a place they were visiting for the summer. And when they’d return the following year, they’d be the ones to tell their younger peers about the campus. That growing sense of ownership was beautiful to witness.”

Babbs, who was invited to serve on the board of Horizons National for a time, emphasizes the importance of Horizons’ power to connect CA with the larger community. He personally spent time on campus during the summer to build relationships with Horizons students.

“If you’re a head of school, it’s called a ‘walkaround,’” he explains. “I’d go to the classrooms often, in part just to see what was happening, but largely so the children could identify with me and with CA. ‘That’s our Head of School,’ they’d say. It sanctioned Horizons as a fully integrated part of our school. They belonged.”

When Mike Davis’s daughter Eliza volunteered with Horizons as a CA Upper Schooler, and later when she returned from college to be an assistant teacher, she gained tremendously, Davis says.

“Eliza got a better sense of the world and the human experience, and how her own actions could make a difference. It set her up to be someone who is very outwardly focused in caring for others and understanding her responsibility to volunteer, to give back, and to help make the world a better place.”

Horizons Colorado, argues Davis, is one answer to the fundamental question that guides CA forward: How can we do more?