For David Schurman ’16, the last six months of 2022 brought a distinguished series of honors.

Perennial, the company he founded with fellow Brown University alumni Jack Roswell and Oleksiy (Alex) Zhuk, was featured among Time Magazine’s Best Inventions of 2022.

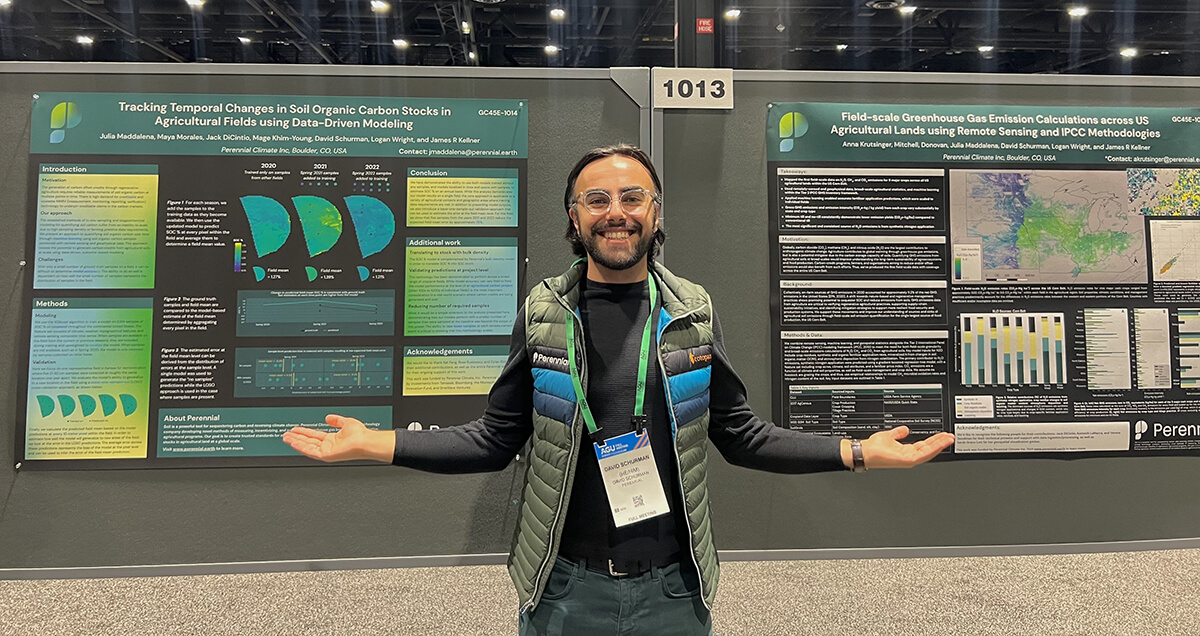

Schurman, who is the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of Perennial, was accepted into the Forbes Technology Council, an invitation-only community for world-class CTOs and technology executives.

And finally, Schurman—along with Roswell and Zhuk—was named to Forbes 30 under 30 in Social Impact.

In May 2022, Perennial raised $18 million in series A funding—a sign the company has shown progress in building its business model and demonstrates the potential to grow and generate revenue.

But Schurman is not resting on his laurels. If anything, he acknowledges the recent recognition with a healthy amount of humility.

“Awards are nice, but the ultimate measure of success is whether you can do what you set out to do and have impact on the world,” he says. “It’s not too good to be pleased with yourself for too long when there is so much work to do.”

His “work” is climate science. Perennial wants to mitigate the effects of climate change, what Schurman calls “the problem of our generation.” The company is literally going back to the farm, incentivizing farmers to use “climate smart agriculture”—regenerative agricultural practices that pull carbon out of the air—and then measuring their progress.

From Earth to Mars

Listen to Schurman, and you hear the weight of responsibility he feels for his work. At Brown University, he opened a TedxBrownU talk by saying, “To tell you the truth, I’m scared, scared about what is happening to our planet. Global warming is more of a problem than it has ever been before. The more ‘hottest years on record’ we have, the more we will be threatened by rising sea levels and extreme weather events.”

Schurman traces his interest in climate change to his days at Colorado Academy, when he and Nick Bain ’16 received the Jennifer Wu Fellowship. They headed to Boulder, to the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The carbon dioxide level had just passed the milestone of 400 parts per million in the atmosphere, and the two Seniors had what they thought was a “huge solution for a huge problem.”

Their idea was to “brighten” clouds over the ocean by seeding, enabling the clouds to reflect more sunlight away from the Earth, thus cooling the planet. Their proposal is referred to as “geo-engineering,” the act of intentionally adjusting Earth’s climate to counteract the effects of global warming. The idea had started in conversations over lunch at CA. Today, Schurman says “we were in way over our heads,” but he also credits Bain with motivating him to translate “weird ideas” into action.

“Nick would not let the idea stop at being just an idea,” Schurman says. “He wanted to try it, and he is still like that today. I owe a lot to him.”

His cloud-brightening research left Schurman disillusioned about the potential unintended consequences of geo-engineering. After he arrived at Brown, he turned to work that took him far from the Earth—to Mars. While still an undergraduate, he joined a collaboration between California Institute of Technology and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, working on software to help scientists analyze what the rover “Perseverance” found in its search for past life on Mars.

In Pasadena, he also connected with Roswell and Zhuk, who had started a new company in a garage. At the same time he was writing software to use spectroscopy in the search for past life on Mars, he was writing code for a nascent company that used spectroscopy to look at life on Earth. For nearly two years, he worked at the business that would become Perennial, worked for JPL, and still managed to finish his college degree—early.

The promise of soil carbon

Within a few years, Perennial graduated from a garage and turned its attention to the promise held by soil carbon.

“Plants naturally pull carbon from the atmosphere and leave some of it in the soil,” Schurman explains. “If you farm in a certain way that makes that happen faster, this could be a way to solve climate change.”

In Schurman’s 30 under 30 honor, Forbes describes Perennial’s goal: “In hopes to unlock soil as the world’s largest carbon sink, the Boulder, Colorado-based company uses artificial intelligence and remote sensing to help farmers optimize and monetize a switch to regenerative agriculture practices.”

What strategies does Perennial advise farmers to use? Plant more diverse crops, apply fewer chemicals, don’t till the soil, change livestock grazing patterns—these are all techniques that Perennial incentivizes with farmers and then measures real outcomes. They are techniques that do not have large negative consequences for the environment—they just accentuate what plants are already doing: pulling carbon out of the atmosphere and keeping carbon in the soil.

For someone who is “scared” about climate change, who felt the weight of responsibility for finding a solution as far back as high school, this is one major step forward.

“I see soil carbon as a solution because we already have the infrastructure we need,” Schurman says. “There is already a farmer on every piece of arable land on Earth. All we have to do is get the incentives right for them to make a switch to regenerative practices.”

A CA work ethic

In his work today, Schurman still draws on his CA experiences in Upper School. He was a Senior Portfolio student with Katy Hills, and he credits his art classes for teaching him to express himself and communicate with others, skills he still uses.

“All the projects I have worked on in tech have had a visual demonstration component,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if you build something cool if you cannot talk about it or interact with it.”

His experience with Kimberly Jans in Computer Science has also stayed with him.

“No matter how good you were at computer science, Ms. Jans always had something for you to tackle,” he says. “I was far from the best student, but for all of us, she always had a new challenge that pushed the limit.”

He credits the “pure critical thinking and deep analysis” of Senior Seminar with giving him the chance to “answer questions that don’t have answers, stretching your brain in new ways.”

Finally, he remembers CA as a place that built his work ethic. “Whatever I did at CA, I was serious about it and tried to do it to the best of my abilities,” he says.

That considerable work ethic is now focused on a solution to an overwhelmingly large problem with implications for the future of the planet. But Schurman is laser focused on doing everything one person can to address climate change.

“We believe soil has huge potential to remove carbon from the atmosphere, but we have to prove it,” Schurman says. “Still, it feels good to be working on the right solutions to the right problems.”