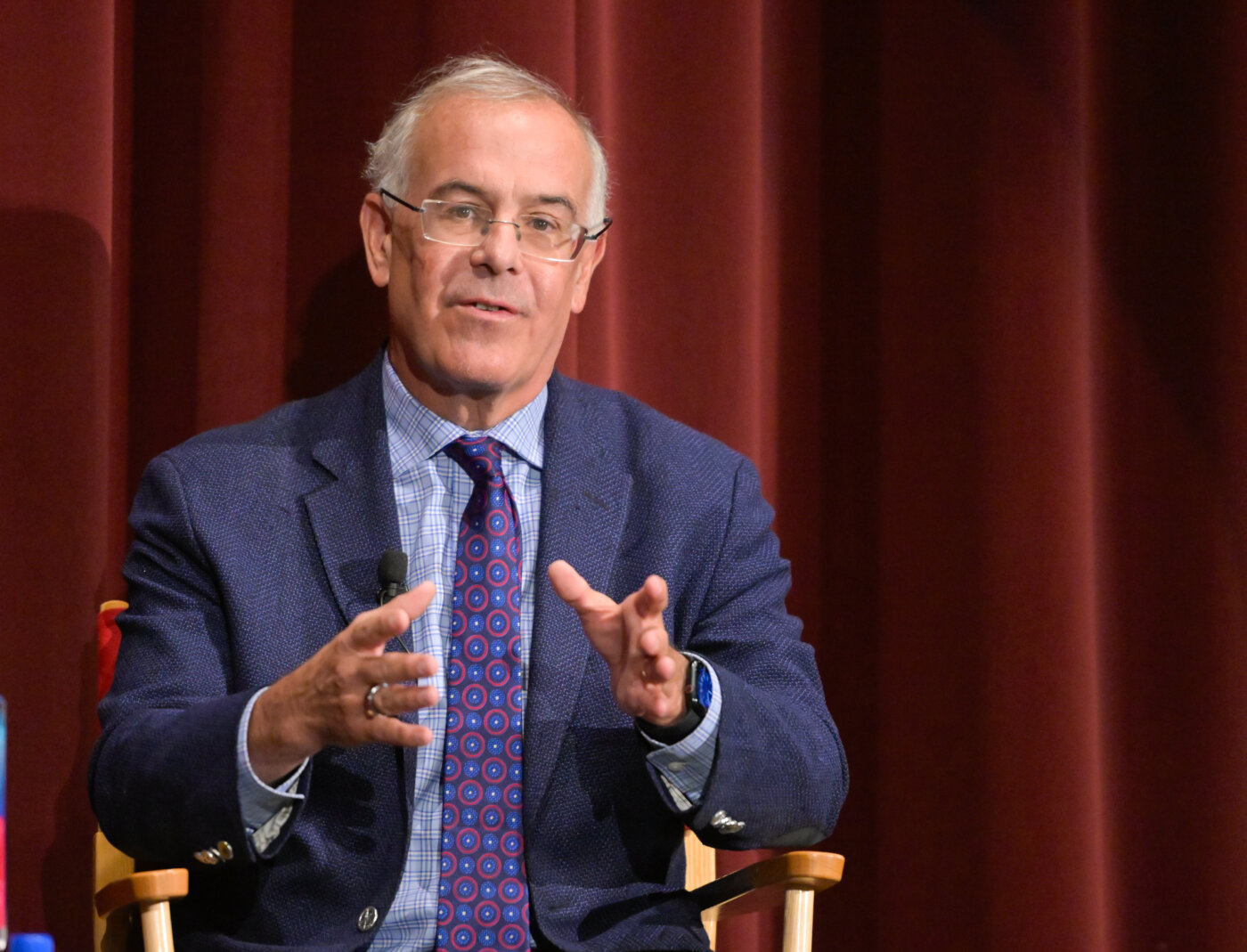

When honest, unrehearsed remarks about the U.S. Presidential candidates’ September 10 debate performances served as the warmup in front of a full house in the Leach Center for the Performing Arts, everyone in attendance knew the first event in Colorado Academy’s 2024-2025 SPEAK lecture series—a morning with New York Times columnist and best-selling author David Brooks, moderated by Head of School Dr. Mike Davis—was going to be something special.

“I had a lot of questions about Kamala Harris going into her campaign,” Brooks told the audience of around 500 CA parents, grandparents, guardians, faculty, and other guests on September 12, “but I thought the Democratic National Convention was masterfully run, that her speech was very well conceived, and I felt that her debate performance was pretty fantastic—mostly because I think she and her team know that she’s behind.”

The rest of the hour-long conversation only picked up speed, and depth, from there, as Dr. Davis floated questions that allowed Brooks to share many stories and morsels of wisdom from his decades of reporting experience around the world. As a front-row witness to history-making events and as a constant learner whose curiosity about others—and about how he might become the best version of himself—has connected him to countless world leaders and ordinary people alike, Brooks is one of the most respected thinkers and writers of our time.

Over the summer, all CA faculty and staff members read Brooks’s latest book, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen. Like the audience, Davis was eager to hear the author’s views on what has become a school-wide theme for CA this year, during which one of the most consequential election seasons in recent memory is unfolding in real time: “How do we hold on to our commitment to civil discourse when we are navigating political divisiveness that’s very real, even among the families gathered in this theater?”

“That’s my job,” Brooks joked, before admitting by way of an anecdote about a screaming confrontation with a fervent Trump supporter at a baseball game that even he finds it all too easy to take disagreements about the future of the country personally. “I would like to think that I rose to that moment and said, ‘Sir, let me understand your point of view,’ but I did not.”

He continued, “And what I’ve learned since then is that when someone comes at you with a critique, your only job is to ask them more than once, ‘How did you come to believe what you do?’ Because that way people are telling you a story about their personal experience. And though you probably won’t persuade them, at least you are able to establish respect in the conversation.”

Every conversation, Brooks observed, has two levels: the back-and-forth discussion about the ostensible topic, and the underlying flow of emotions between the parties involved. “Are we making each other feel safe and respected in this conversation? When that’s not the case—when your motivations deteriorate, and it becomes about who’s smarter or who’s tougher or who’s more powerful—you should just shut up. Everything you say is going to be unhelpful.”

Davis wondered, “Beyond listening and treating people with respect, how can we rebuild trust in our country at this moment?”

In answering, Brooks cited several telling statistics about trust in the United States. Two generations ago, he recounted, 60 percent of Americans would have said that they trusted their neighbors; today, that number is below 30 percent, with the Millennial and Gen-Z generations saying it’s even less. “This is the first time in our history that younger people are more distrustful than their elders.” He added another data point: 75 percent of those younger generations agree with the statement, “Most people are selfish and out to get you.”

“Young people especially,” Brooks explained, “often feel that they have no agency in their lives. They feel betrayed by people they know, and by the institutions around them. So we live in a cynical ethos.”

At the same time, he noted, many Americans are growing up without having learned the moral and social skills that are required to support the foundations of trust: relationships between people. “Our society does a poor job of it, but if you can get people in the habit of knowing that deep, relational life is just a part of life—it is just ‘what we do here’—then everybody will behave that way.” The importance of establishing norms of community action and social interaction can’t be overstated, Brooks argued. “The thing that all of us want most in the world is to be understood in our full being.”

What led him to this perspective on relationships and connections? Davis asked. Time and a dramatic personal transformation, Brooks revealed. “I got to a point where my kids were heading off to college and my marriage had ended, and I was just painfully lonely. I had only work ‘friends’; my weekend friends all drifted away. It made me realize I’d been living by the wrong values. I realized that only spiritual and relational ‘food’ can really fill the depths of your being. I had to shift from a pretty normal, career-focused ethos and try to have a new consciousness about living. I was determined to be open.”

Brooks recounted numerous stories of friends and acquaintances he’s made since that transformation, all proving to him that vulnerability, emotional honesty, and care for others are fundamental in nourishing individuals and communities—and classrooms, too, he added.

“What can schools like CA do to better prepare our students to be good citizens and good people?” Davis wanted to know.

It’s unfortunate that we’re all trapped in a system called a meritocracy, Brooks conceded. “The institutions we use to educate young people are also used to sort them—to measure children’s value through testing. But what’s clear is that IQ and test results are only a small part of what accounts for success in life. To me, what’s most important is having the intense curiosity and the desire to keep learning all through one’s life.”

Character development is also critically important in schools, he went on to explain. “The very best teachers create moral ecologies,” Brooks stated. “In their actions and gestures, they show everyone how we accomplish things together.” To that end, teachers in all schools deserve more leeway and more freedom from the demands of standardized testing, and their unique ability to fill the emotional and spiritual void that young people sometimes feel should be celebrated. “Teachers are the ones who can help show students what it looks like to live a moral life—whether it’s stoicism or Buddhism or whatever tradition it may be. That’s formation, not just education.”

Yet in today’s schools, teachers and students are more hesitant than ever before to engage in difficult conversations that could lead to real understanding. “It shouldn’t be that hard to teach two opposing facts: that this is a great country, and that this country has done awful things. But somehow teaching that in today’s classrooms gets you in hot water.” The reason, Brooks believes, is the tyranny imposed by the very small minority of people who yell the loudest. “In my view, it’s the job of the head of any institution to push against that incivility—to be tough and punish it sometimes. Then people have permission to feel safe.”

Ultimately, however, Brooks thinks that our country is less divided than the “conflict entrepreneurs,” as he describes the voices playing to the extreme sides of every debate, would have us believe. “Our basic ideas about living are very much the same, but there are just a few key differences.” The first is the growing divide—in income, health, life expectancy, social connectedness, and nearly every other measure—between college-educated and non-college-educated Americans.

“We have created a system that divides America starting at an extremely young age—seven or eight. Being good at school is not necessarily being good in life, but we’ve made the mistake of thinking that, and that that’s how we’re going to sort people for the rest of their lives.”

“We need a new definition of merit,” Brooks concluded, “one that’s more evenly distributed through society, one that includes curiosity, love, generosity, and honor. I think what defines the human heart is not IQ. It’s the passions of the heart, the longings of each individual.”

Time for class

Students and the role that school can play in nurturing their passions were much on Brooks’s mind during his SPEAK remarks in the Leach Center, and a group of students in the Advanced Studies and Research (ASR) course Superpowers: China, Russia, & the United States in the Modern World played the central role in the next stage of his CA visit.

Brooks sat down for a discussion about international relations in CA’s Speech & Debate classroom with the Juniors and Seniors, along with Senior Instructor and Social Studies Department Chair Liz Sarles. He shared stories of being present in the 1990s at the end of apartheid in South Africa, Middle East peace talks, and the end of the Soviet Union. “All around the world, history seemed to be converging on peace and prosperity,” he told the class.

“But in the years since,” he continued, “it seems like it’s all been getting worse; the world seems much more threatening than it did in 1990. How do you feel about the world today?” Brooks asked.

Senior Jake Keil observed, “The world may seem more threatening, but I think part of that may be the way news can spread so quickly now: Something happens, and within a minute you can see it on the other side of the planet.”

Fellow Senior Meg Stanitski added, “Some of the unease could be coming from the fact that it’s not a unipolar or bipolar world anymore. Power doesn’t seem as concentrated, and it feels as if some shift might be on the verge of creating a new balance of power.”

And another Senior, Charlie May, chimed in, “As long as China sees the Western democracies as an obstacle, then I think we’re seeing almost a new Cold War centered on chip manufacturing.”

Brooks posed another question to the group. “How much do you think a nation’s foreign policy is determined by its economic self-interest?”

On the one hand, some students argued, international relations and domestic safety always have to be balanced against economic gain, which in many ways is inextricably linked to global trade. But on the other hand, goes the opposing view, countries such as China are making moves toward greater economic independence from the West, reducing that tension between diplomacy and economic growth.

In response, Brooks asked students to reflect on Europe at the turn of the 20th century, when trade and economic fluidity were perhaps greater than they are today in the European Union. “What happened a few years later? World War I. Economics plays a powerful role, but nationalism, too, is a major force. Russia didn’t invade Ukraine 2022 for economic reasons, particularly. Culture shapes history.”

Rarely good versus evil

Brooks, Sarles, and her students returned to the Leach Center’s stage for the third part of this special event. Upper Schoolers filled the theater, as the group continued their discussion with Brooks with new questions.

Upper School Principal Max Delgado introduced Brooks to the Ninth through Twelfth Graders and explained why the topics in which Brooks specializes are so important at CA. “You’re already learning what will be a critical skill for you in the world you encounter after CA: engaging in the hard work of building human relationships. What Mr. Brooks is going to encourage us to do is to talk and listen in ways that add harmony to the world instead of confusion—something that you’ll have to do for the rest of your life. Being able to practice civil discourse and have hard conversations is the key to expanding our understanding and deepening our connections with one another.”

Noting that a recent survey of Upper School students painted a mixed picture—the student body feels educated about current events, but feels less comfortable sharing and debating their views—Sarles said, “CA has more work to do in creating space for civil discourse, and we hope that, witnessing this conversation between students and an accomplished adult, you’ll get to see a demonstration of what meaningful dialogue can be.”

Jake Keil went straight to the point with his first question for Brooks: “How would you suggest we stay civil while discussing politics in school as we approach a major presidential election?”

Brooks was ready with practical advice for the students. “When you’re in a disagreement, keep the ‘gem’ statement in the center—the thing you both agree on deep down. That preserves the relationship despite the disagreement.” Second, Brooks offered, find the disagreement under the disagreement. Third, “Treat attention like an on/off switch, not a dimmer. If you’re with someone, pay 100% attention; don’t 60-40 the conversation with your phone in your hand.” Other conversation tips included being an active listener, trying to avoid “topping” a point someone’s just made, and not being afraid of a pause.

Most importantly, Brooks emphasized, ask questions. “All of you in this room are phenomenal question-askers; I know because you were all once four-year-olds. But somewhere around adolescence, we begin to lose that ability. But I believe that regaining that childlike curiosity is one of the greatest skills you can cultivate.”

Junior Abby Dawson homed in on another pressing question for this political season: “How has social media affected our ability to see and hear each other?” Brooks turned the table on the student and asked for her view. “I think there’s two sides of social media. There’s a side that’s really positive, where people can find a community and others that they agree with, and see other people’s points of view. But there’s also the side where people are bringing each other down, and there’s misinformation being spread.”

Brooks agreed, “I used to think that it was what people brought to social media that caused such negativity. But I’ve been convinced otherwise. When I look at the rising rates of depression, loneliness, and anxiety among young people, I place a lot of the blame on social media. When you’re surrounded by negativity, and you’re also having fewer experiences of being with people face to face, real relationships are being replaced by something that’s a distraction.”

A follow-up question from the group prompted Brooks to reflect on one of his favorite topics, character formation. “The number-one goal of schools used to be turning out young people of character. At a school like CA, that’s still the case, but it’s not so at most. There used to be classes in courtesy—you would learn humility. The big question is, how do you become a better version of yourself? Learn about amazing people. Identify what are your weaknesses and work on them.”

But the biggest area for growth, according to Brooks, is moral skill. “How do you break up with someone without breaking their heart? How do you host a party so that everyone feels included? How do you sit with someone who is depressed? The answer, in each of these cases, is, again, listening, demonstrating respect and goodwill, and valuing relationships first.”

The day’s final question, from Charlie May, helped put Brooks’s visit to CA in clear focus. “How can education in the United States better prepare students for civic engagement and participation in a democracy like our own—especially considering the fact that there are millions of young Americans each year who do not vote?”

Brooks told the audience of high schoolers, “First, I would encourage everybody to care about politics. Politics matters—a fact that’s brutally apparent in societies where you can be imprisoned for your opinions or be forced to pay a bribe to run a business. Second, I would remind you all that politics can do good. Sure, there’s corruption and fundraising and dishonesty, but on the whole, most politicians are good people.”

“My generation has left your generation with a lot of problems,” Brooks acknowledged at the end of his remarks. “One solution for you all to consider would be something like a national service program—where all young people are forced to encounter ideas and cultures outside their own lives. Because one of the biggest fantasies in politics or international relations is that one day the other side is just going to go away.”

But as with Israelis and Palestinians, there’s always going to be the other side, Brooks observed. “Have the civil conversation. Take it out of the realm of fury and reduce it to practical details. In our country, the assumption that both sides have a piece of the truth is usually a good assumption. That’s basically my approach to most every problem. It’s rarely good versus evil.”