The catchiest tune in the blockbuster Lin-Manuel Miranda musical Hamilton is “My Shot,” in which a young Alexander Hamilton raps about his hopes for the future, his disillusionment with the British, and his desire to be remembered. The revolutionary and future Founding Father repeats the song’s instantly recognizable chorus a half-dozen times as he delivers an autobiographical epic:

I am not throwin’ away my shot

I am not throwin’ away my shot

Hey yo, I’m just like my country

I’m young, scrappy and hungry

And I’m not throwin’ away my shot

After classes have ended on a January afternoon at Colorado Academy, 16 Middle Schoolers are singing the words to “My Shot” in almost perfect unison while tidying up the Raether Innovation Lab, where the students have worked together one or two days a week over the past six months to design and build Caelum, their entry in the global Future City Competition.

Caelum, Australia, “known as Sydney before the Great Fires of 2052, means Heaven in Latin,” the Future City team’s competition essay begins. “Caelum rose from the ashes between the Hawkesbury River and the Australian Pacific coast with a population of 350,458. Citizens rebuilt to eliminate urban poverty intensified in every way by the climate crisis, including water availability, food security, and energy production. Sea level rise, extreme heat, and weather events made poverty more widespread. Caelum combats these problems to create a sustainable, innovative, and equitable city.”

The team’s entry, which includes the deeply researched and thoroughly referenced essay, along with a scale model of Caelum, renderings, and an elaborate staged presentation, won the 2023 Colorado regional Future City competition in January, earning the students a spot in the national finals in Washington, D.C., over the Presidents Day weekend in February.

CA’s Future City team was also the regional winner and competed on the national stage in early 2022, but COVID-19 severely impacted that year’s competition, with events taking place over Zoom.

Showcasing the work of other winning teams from around the world, and finally taking place in person again, this year’s finals were, indeed, the CA students’ shot at proving their hard work, engineering knowledge, team building, and creativity are up to the challenge posed by one of the most pressing issues facing the world today. And though their efforts didn’t earn any awards this year, the team’s trip to the finals showed they deserved their place alongside the winners.

Every type of learning

A hands-on, cross-curricular educational program that brings STEM to life for students in Grades 6 through 8, Future City asks students to imagine how to make the world a better place and challenges them to envision a city, 100 years in the future, that solves a major sustainability issue. This year, students set out to tackle climate change, using the principles of engineering design and deploying project management skills to plan a sustainable city of the future.

According to CA’s Future City team members, the climate crisis offered rich territory for exploring both engineered solutions and social and political change.

Eighth Grader Ben Zinn, the team’s essay project manager, says, “We chose to focus our project on urban poverty, which was really interesting, because it’s not always thought of with climate change. We did a lot of research into how poverty and climate change affect people and what we could do to improve this in the future.”

The team’s general project manager, Eighth Grader MJ Seitz-Yanez, adds, “Exploring this broad topic really brought into focus a lot of the smaller things that you might not realize. I never knew how much urban poverty is worsened by climate change—with people losing their homes, not having food security, not being able to support their families. It’s really interesting being able to see many different sides of things and still have an amazing project in the end.”

Middle School science teacher Kathleen Kirkman, who is a faculty co-sponsor of Future City at CA, along with Educational Technology Specialist Laura Farmer, elaborates, “Through their research, the students discovered how the impacts of climate change—extreme heat, natural disasters, wildfires, food deserts—are much worse for those experiencing poverty, and they wanted to solve that problem. They had to dive into the nuances around the causes of poverty and think about how they could design adaptation and mitigation strategies to address these.”

Ultimately, explains Kirkman, the team focused on designing for equity, by doing things such as making neighborhoods walkable, with no private vehicles and free public transit. The students proposed subsidizing their solutions through surplus energy created with innovative technologies like lightning farms and solar-energy-gathering satellites. Their city plan is chock-full of other innovations, such as vertical farming towers, rewilded green spaces, high-density housing designed for natural heating and cooling, plant-based food production, nanobot-delivered health care, holographic school classrooms, police robots armed only with non-lethal technology, and mass transportation aboard electromagnetic hovercraft.

The wide-open nature of the Future City challenge and the many ways students are encouraged to respond to it draw on nearly every type of learning, Kirkman says.

“There’s the Design Thinking piece, which is about prototyping, multiple iterations, and evidence-based reasoning. There’s doing the research, evaluating whether information is authoritative, and citing their sources. Students do a lot of math when building the elaborate model to scale, they use their creative side as they craft and paint everything, and they practice expository writing in the essay that lays out their plan. There’s even social studies, because they have to set up a government for their city, decide how to tax the population, and fund social services and other needs.”

CA has “Six Cs” that guide all teaching and learning: critical thinking, collaborating with others, creativity, communication, character skills, and cultural competence. Future City encompasses all six of these pillars, argues Kirkman.

Over 15 years of being involved with Future City teams, both at CA and in previous schools, she says, “I have seen kids learn more in this program than any individual class or project I’ve ever done.”

The team experience

Throughout the fall, team members worked together in small project groups—on a deadline and with a budget limited to $100—to complete all the required elements for the competition. Project managers for the essay, model, and presentation components and the project as a whole kept everything on track, negotiating with each other when needed if there was ever a disagreement about an element that more than one group was working on, such as a transportation concept that was described in the essay but not depicted in the model.

Nina Oren, the Eighth Grade project manager in charge of the Caelum model, joined Future City for a second year, after competing with the region-winning team last year. She explains, “I don’t usually do a lot of engineering stuff, so this was a fun new experience. My job was to give everyone their individual tasks on the model. Once they finished their tasks, I would give them something new to work on. I didn’t do a ton of the actual building, but I would walk around and see how people were doing, and help out if someone was missing.”

Fellow Eighth Grader Olivia Nelsen, who was new to Future City, adds, “At first when I started this project, my mom just really wanted me to be more social in the CA community. I didn’t realize how much I would end up loving it. The commitment that you put into it really shows in the end, and I made friends with so many people who are outside my usual friend group. It also taught me to be flexible, because plans changed almost every minute. It could be something minor like fixing a grammatical error or rewording something in the essay, or it could be completely reconstructing our housing units.”

Ben Cushman, a Seventh Grader who built and painted the model background with Nelsen, says, “This was a very time-consuming project, so you had to be really committed to it. But it was a lot of fun, because you got to spend two hours with your friends after school.”

And according to Seventh Grader Farah Arnold, “Even though it takes a lot of commitment, for a lot of us here this is what we want to do and be when we grow up. I think that’s why we take time to be so dedicated.”

While they were at work on the project deliverables, the students were also consulting with experts and going on field trips in order to gather background material and find inspiration for Caelum.

They met regularly with Jennifer Bartlett, Capital Planning Lead with the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure for the City and County of Denver. Bartlett (Kirkman’s wife) shared her urban planning expertise with the students and connected them with engineers working on sustainable energy and water technologies and AI-guided transportation systems.

And along with CA’s Middle School Robotics Team, they visited Outrider in Brighton, where they got to see the company’s autonomous and fully electric freight trucks and question the engineers about what they thought autonomous vehicle technology would look like in 100 years.

“Speaking with experts about technologies that are just emerging today, students realized things are changing so fast that few can predict where their fields will be in the distant future,” observes Kirkman. “That allowed them to be creative, envisioning solutions we can’t even imagine right now.”

Kirkman sees particular value in the exposure to engineering that Future City affords. “Most middle schoolers don’t see opportunities in this field. I’ve had parents tell me, ‘I wish I’d known about engineering earlier.’ Even people who become engineers often don’t consider it or don’t think about it until college.”

Future City, Kirkman continues, requires students to think like an engineer throughout the entire project, and they learn firsthand from professionals in the field—not only during the design and build phases, but also in competition. Judges are professional engineers who closely evaluate the students’ work and ask them questions about their design and process.

“For middle schoolers,” she says, “this is the first time they begin to understand that engineering is not just being good at math. It’s about building, designing, and creating. It’s art; it’s research; it’s working with other people. It’s all of that.”

Kirkman notes that Future City draws in participants with a huge range of interests and talents, allowing them each to find their niche in the world of engineering.

“It takes writers, artists, builders, and even performers to pull off the final project.” With a majority of this year’s team members also participating in the Middle School musical, Kirkman says, the presentation they put together for competition was “phenomenal.”

Regionals and beyond

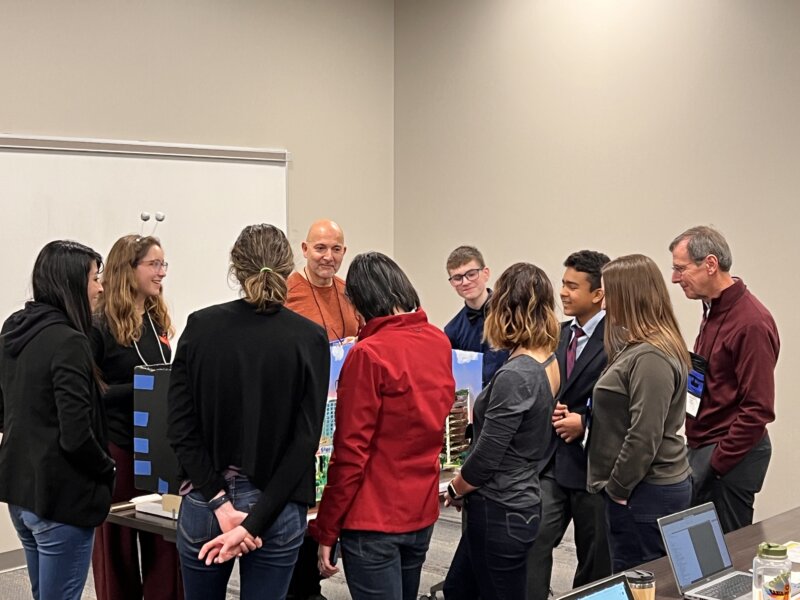

At the regional Future City competition, held on January 21 at the Colorado School of Mines, the CA team’s polished presentation, visionary essay, and detailed model clearly impressed the judges, capturing first place and qualifying them for nationals.

According to Seventh Grader Rahul Iyengar, who relished working on the Caelum essay and presentation, “Winning regionals was my favorite part of this school year so far—not really because of the competition aspect, but mainly just working together with all my friends and seeing how six months of work came together so beautifully and amazingly.”

During the presentation, Iyengar, Oren, and Zinn told the story of a space traveler who visits Earth to help its residents cope with climate change. The visitor is surprised by the Earthlings’ innovative solutions, and she is impressed with Caelum’s 15-minute city plan, which puts nearly everything people need to live within a short walk or free public transit ride.

Explains Arnold, “It was so much fun to be at regionals, because we got to spend the whole day talking with other teams about their ideas.”

And for Nelsen, “It was incredible. We had to accept the fact that if we lost, it would be okay. But at the same time, we had to stay humble when we were announced as the winner.”

Kirkman says, “What’s on my mind right now is celebrating the hard work these kids have put in all year. They’ve been here every week; they’ve come for endless study halls. They’re feeling so good about the culmination of this experience.”

Still, going to the national competition was an undeniably exciting prospect for many team members.

“Going to Washington really made up for last year,” says Eighth Grader Peter Hedstrom, who was the presentation project manager. “I was really looking forward to competing in person.”

Oren adds, “Nationals were an incredible bonding experience.”

But most students on CA’s Future City team are circumspect when it comes to the importance of winning.

Says Zinn, “I’m not as concerned about the results of the competition. It was just fun to go to a different place with this team that I’ve spent so much time with, and enjoy a new place and a new environment.”

Arnold acknowledges, “Washington wasn’t about winning. It was about having that experience and being able to talk to other teams, share ideas, and just think about what our future is going to look like compared to what the world looks like now.”

“It’s really exciting to see—maybe it won’t be in our lifetime—but that some of these ideas will actually be put into use and really positively help climate change,” says Nelsen. “It’d be great to see that an idea formulated by 16 Middle School students is now a global thing that helps everyone.”