Some might say that Fourth Grade flies under the Lower School radar. It doesn’t seem to reverberate as loudly with the dramatic leaps in reading and math that occur in earlier grades, or foreshadow the more rigorous academic schedule of Middle School in the way that Fifth Grade does.

But for Colorado Academy’s Fourth Grade teaching team, a little bit of stealth is a good thing.

Explains Instructor Afaf Saoudi, “Fourth Grade is that hidden sweet spot, where they still want to please the teacher, but they also appreciate being challenged. Their curiosity about the world is at its peak, and they’re inspired to be able to lead in their own learning in an authentic new way.”

“They see everything through goggles full of joy and vibrancy,” adds Senior Instructor Jeff Brown. “We have the privilege of helping them harness that energy and run with it.”

In CA’s Fourth Grade program, students take the reins by delving into self-directed research projects on the 13 American colonies, the Revolutionary War, Western Expansion, and the National Parks system. The robust social studies curriculum ties closely to their work in language arts, where they synthesize their research findings, write up science lab reports, and do far more “reading to learn” than “learning to read.” Students go deeper with mathematics and science, as well, exploring larger numbers and seeking their own strategies to help them approach more complex problems and scientific challenges.

At some point during their Fourth Grade year, observes Brown, “Most students seem to find a new passion, a new sense of direction. The agency we encourage helps them discover what they truly enjoy and understand themselves more fully as learners.”

Says the senior member of the Fourth Grade team, Preceptor Chris Hertig, “They love the freedom to pursue what they’re learning in almost any direction they want.”

An expanding view

That growing self-awareness begins with social studies and expands across all disciplines. Units looking at the complexities inherent in American historical periods demand research into multiple perspectives and spark reflection, debates, and new ideas.

“Because we do so much research through the year,” offers Saoudi, “students begin to make sense of their ‘writer’ identity. Planning, drafting, revising—these are relatively new skills for them, but through the process of going back to their work and asking what more they could do, they really get the opportunity to take ownership as an author.”

Brown’s oft-repeated maxim is, “Writing’s never done—it’s only due.” He and his colleagues challenge writers to examine their own personal experiences, mining them for details and emotions that can bring ordinary moments to life.

Writing for an audience becomes a central focus, adds Hertig. “Compared to Kindergarten and First Grade, when they felt proud to write their name, our students are now generating pages of material while keeping in mind questions such as, ‘Who is this for?’ and ‘What would help them understand my idea better?’”

Meanwhile, during math lessons, the focus shifts from teaching algorithms to nudging students to analyze and explain their own thinking in trickier scenarios.

“We want every child to find their own entry point into a problem,” Brown explains. “For some, it may be more procedural; for others, it could be breaking apart numbers. Whatever their strengths, we want our students to feel confident about the tools they have in their bag and know that they can successfully attack any challenge.”

In science, students learn about the scientific method, performing their first true experiments and evaluating their results in relation to a hypothesis. And in engineering and design, they master digital skills that are essential for research and presentation; through programming and robotics, they examine complex mechanical systems and use data to understand their behavior.

Becoming leaders

Alongside academic subject areas and extensive arts and music offerings outside the classroom, social emotional learning occupies an increasingly significant part of every day for these students. Fourth Grade’s guiding theme for the year is, “How do I lead myself and others in a fair and just way?” The prompt ties into the Lower School’s “Formative Five” skills: empathy, self-control, integrity, grit, and embracing diversity.

Beginning in the first weeks of school, Fourth Graders practice these by pairing up as leaders for their First Grade Buddies, whom they will regularly spend time with throughout the year. Through reading, playing, and completing fun projects with younger peers, the older students learn to carefully balance their instinct to help and guide alongside their recognition that the First Graders are rapidly advancing both academically and socially. “Asking themselves, ‘How can I support this person?’ becomes a key question,” says Brown. “Demonstrating that kind of empathy is a critical leadership skill.”

According to Hertig, social emotional learning has found its way into nearly every classroom practice in recent years with the arrival of Lower School Principal Angie Crabtree and Lower School Counselor Brooke Hamman. “Together, they’ve helped us be more deliberate in teaching about feelings, emotional regulation, executive functioning, and community building.” Every adult and child in the Lower School now knows why it’s important to be an “upstander.”

Saoudi emphasizes that this evolution couldn’t have come at a more appropriate time: “These children were in Kindergarten when COVID struck, and they are still paying the price in areas such as conflict resolution and even identifying their feelings. But in my classroom, it’s important that students can tell me whether they are angry or just frustrated—they are two very different things.”

Self-advocacy is another skill hit by the pandemic, and Fourth Grade teachers know ensuring students can speak up for themselves is vital to their success, not only in this year of school, but also for the rest of their lives. Being a good friend without sacrificing one’s own well-being; demonstrating accountability; taking healthy risks; and bouncing back in the face of setbacks and failure—“We have to be so intentional about working on these every day,” underscores Brown.

Finding their ‘why?’

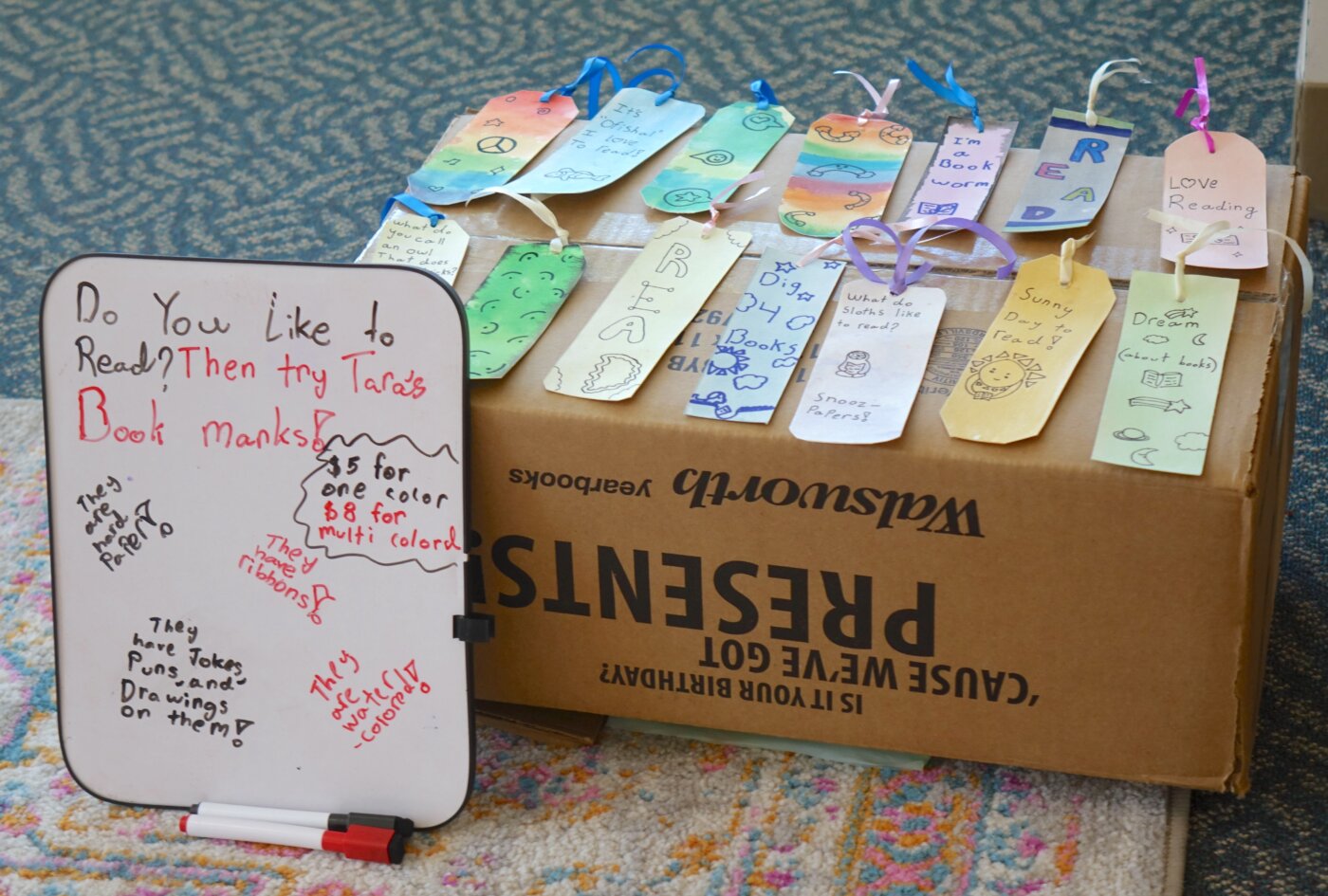

The capstone experience of Fourth Grade, an economics unit called Mini-Society, requires students to call on everything they’ve absorbed throughout their year. Fourth Graders are grouped into self-contained communities and challenged to devise their own distinct “national” identity, monetary system, labor market, and natural resource and trade policies. Each community creates its own product to “sell” to others, and to succeed, students must rely on their abilities to collaborate as a team, conduct market research, balance pricing versus opportunity cost, and draw insights from their knowledge of what worked and what didn’t for the 13 colonies and the Western pioneers.

Students gravitate toward different jobs within their communities: Some clamor to be the ones in charge of designing their money or flag, while others want to create products or manage their “treasury.” The entire month-long unit, Brown points out, “echoes the work we’ve been doing all year around finding your strengths, identifying your passions, and celebrating and sharing those with others.”

At the same time, notes Saoudi, “Mini-Society engages their strategic mind; for the first time, they are in control of all the decisions from start to finish: What kind of product will sell? Where will our community be located?”

This foray into big-picture thinking shares much in common with the kinds of projects the Fourth Graders will be asked to tackle as they continue on to the Middle School and Upper School. It’s no surprise, then, that the Fourth Grade team is working with CA’s REDI Lab and Director Tom Thorpe on taking Mini-Society to the next level.

Thorpe explains, “REDI Lab positions students with the initiative and agency to self-direct their way through a project of their own design. By doing this, the Lab becomes an opportunity for students to develop a clearer sense of their ‘why?’ and recognize more of the value they have to share with the world.”

This mission, according to the Fourth Grade teachers, aligns perfectly with the goals of the Mini-Society initiative. Pressing students not only to dream up a product idea, marketing strategy, and community economy, but also to consider the question of why a given approach makes sense—or doesn’t—offers the opportunity for them to wonder about even weightier ideas: What motivates me? How do my strengths and passions benefit others?

Such open-ended inquiry, notes Saoudi, can be a little overwhelming at first. “It’s no longer a specific assignment that’s due in a couple of days. It’s a whole new way of thinking about themselves as creators, as active seekers of information, as participants with a responsibility to themselves and those around them.”

There are even tears, Brown adds. “We give them lots of chances to succeed and fail: They have to apply for the job they want in their society; they have to respond when the market doesn’t buy their product. The risks and rewards are real.”

But for students, the higher stakes are their own reward. From this point forward, they’ll face increasingly complex challenges, both academically and in the wider world. The idea of civil discourse, of negotiating one’s place within the constructs of school, family, community, and society, will become increasingly critical. And Fourth Grade at CA is, in many ways, where that great adventure begins.