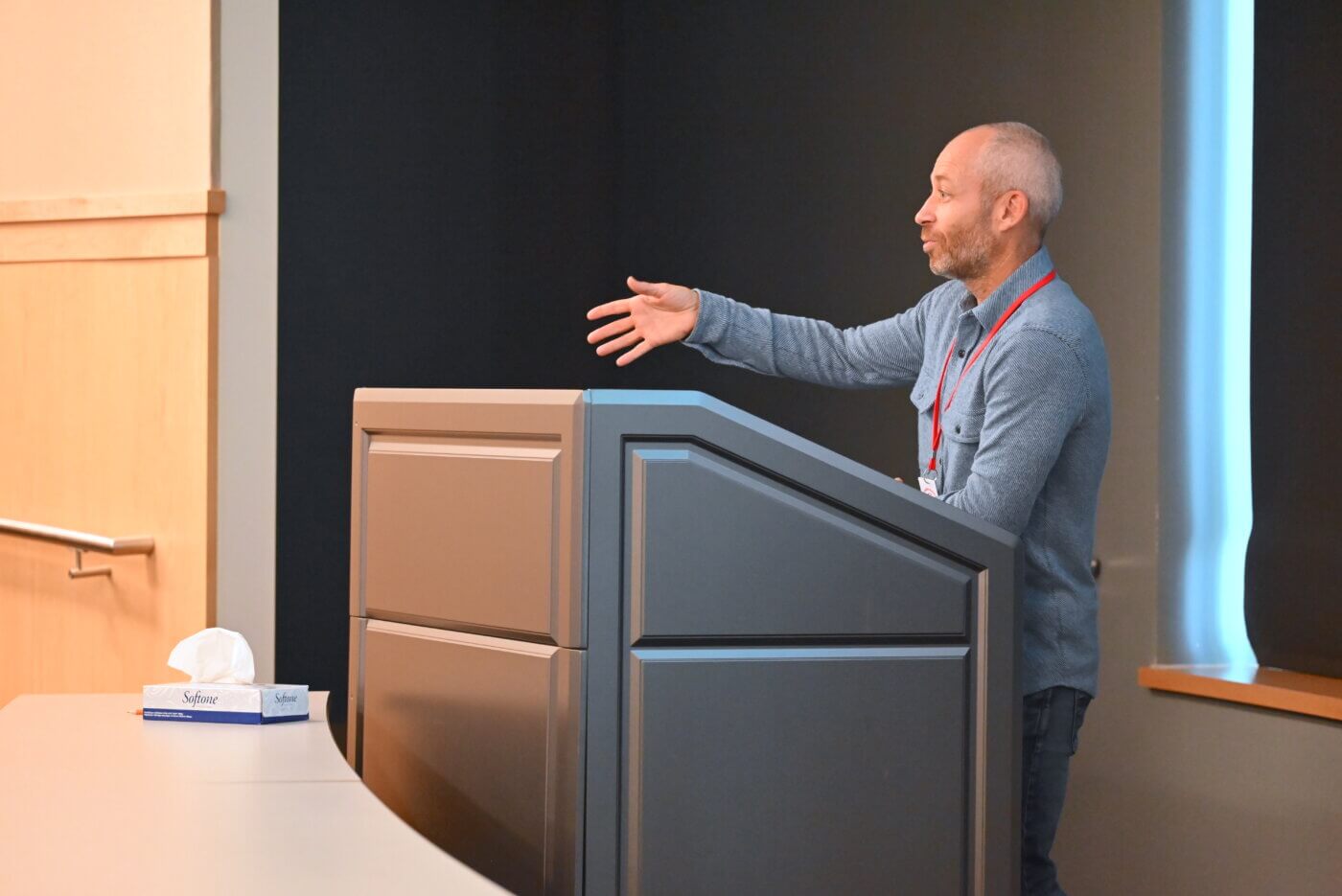

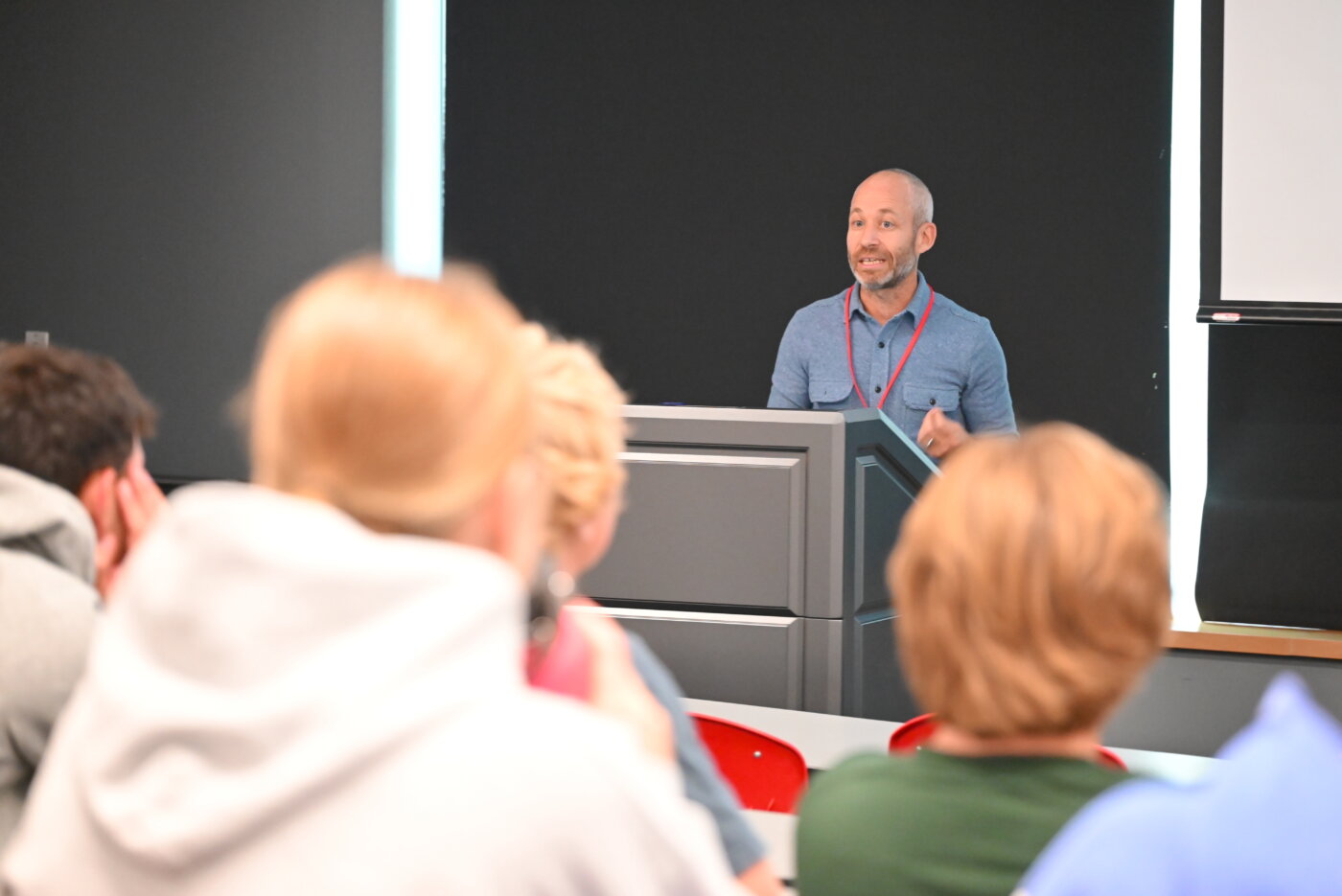

This fall, in a visit to Head of School Dr. Mike Davis’s Upper School social studies elective, The Chiricahua Apache: Understanding Myth & Reality in the American West, noted anthropologist and archeologist Chip Colwell engaged a group of Colorado Academy Juniors and Seniors in a detail-rich discussion of the 1871 Camp Grant Massacre near Tucson, Arizona, one of the deadliest massacres of Native Americans in American history and a pivotal event in the Apache Wars that were central in the history of Western expansion.

Drawing on his award-winning book, Massacre at Camp Grant: Forgetting and Remembering Apache History, as well as his experience with the movement to repatriate Native American cultural artifacts stolen by museums and other institutions, Colwell told students that while many of the perpetrators of the massacre of more than 100 Apache people are memorialized in the names of streets, schools, parks, and mountains in and around Tucson, the victims and the circumstances surrounding the event were until recently remembered only in scattered accounts and oral histories.

Apache culture prioritizes the living, Colwell explained, and dwelling on the past or the dead is discouraged. “To this day, many Apache people don’t know about the Camp Grant Massacre; Anglo-Americans in Tucson know little more than the names. But unraveling the questions of who gets to tell the history of this event and how and why and when history is recalled sheds light on the importance of remembering this period in the American West.”

According to Dr. Davis, the massacre occurred in the midst of increasing American encroachment into the traditional homelands of the Chiricahua Apache, a group of clans and bands in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States that at the time of European contact controlled a territory of 15 million acres across New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico. “The last nation to be subjugated by the U.S. government in the late 19th century, the Chiricahua story is one of resilience and of tragedy.”

But in places where history such as the Camp Grant Massacre is recalled, Colwell added, “This story is most often told from the perspective of people who look like me—Anglo-Americans, the ones who perpetrated the massacre itself.” So Colwell, who is also the founding editor-in-chief of the digital anthropology magazine SAPIENS, consulted with Apache people across the Southwest to hear their oral histories and consult their archives, and he used military records and data collected by archeologists at the massacre site to fill in important details.

Armed with this information, Colwell traced the reasons for the tragedy to 1854, when much of southern Arizona became part of the United States through the Gadsden Purchase and treaty with Mexico. Apache bands had been at war with Mexico, Spain, and each other for a century, and now, Colwell said, “The ‘Apache problem’ became the American problem.”

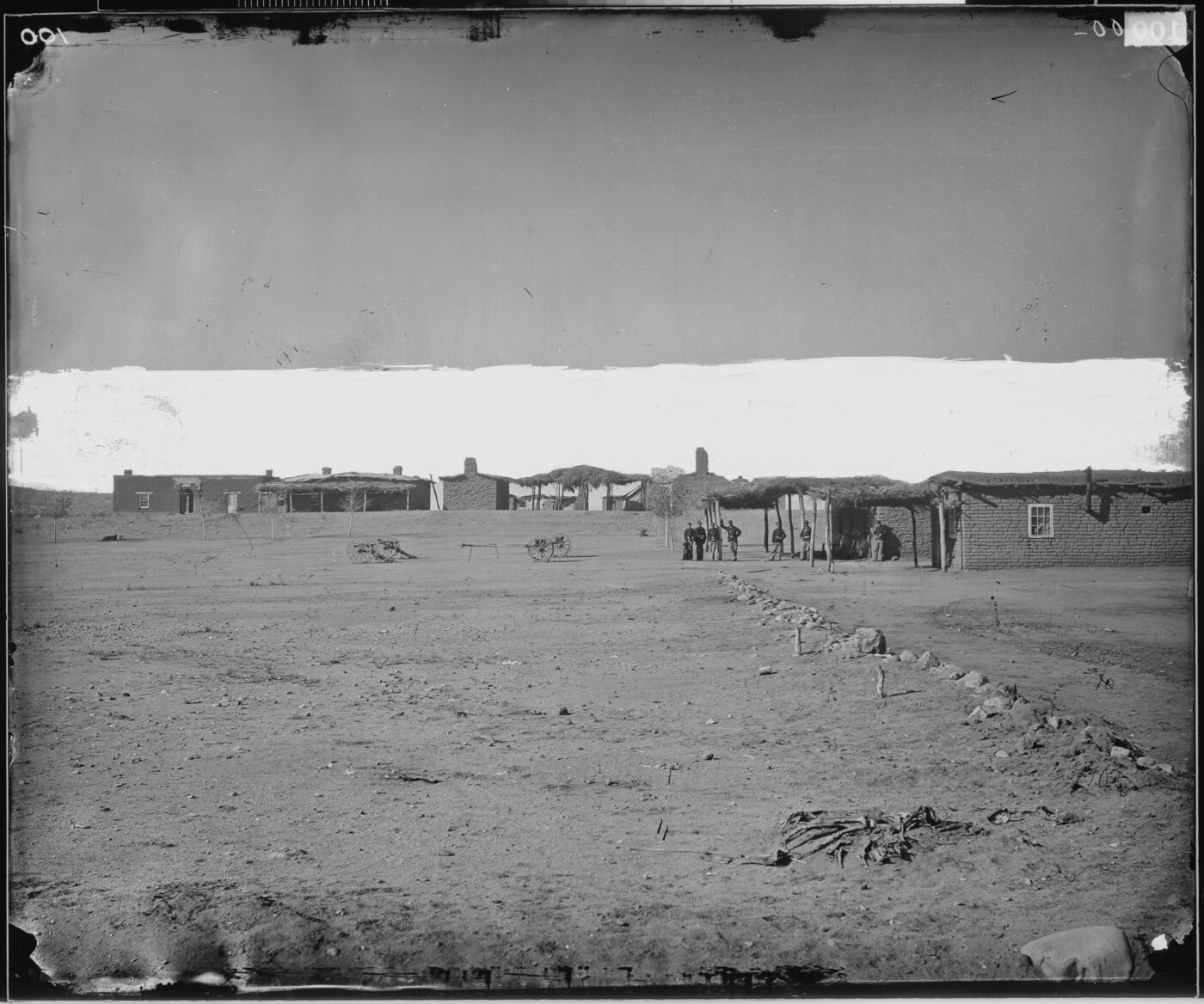

The government sought control over the region by establishing forts and military encampments to try to ensure the safety of settlers arriving to set up mining, ranching, and farming operations. Apache peoples, whose homelands the new arrivals seized, reacted in different ways: Some began raiding settlements and military outposts, while others turned to the U.S. government for protection.

The Pinal and Aravaipa Apache were among the latter group, allied farmers and gatherers who went to Camp Grant in 1870 seeking a permanent peace with the U.S. government. They were accepted as prisoners of war and given an area near the camp to live and cultivate crops, and the moment was seen as a hopeful precedent for future relations between the Apache groups as a whole and the United States, recounted Colwell.

But when Apache raids by other clans continued in southern Arizona into 1871, the people of Tucson erroneously blamed the peaceful Pinal and Aravaipa. According to Colwell’s research, regular counts of their numbers near Camp Grant made it impossible that they could have committed the raids.

Nonetheless, Tucson leaders—including some whose names remain etched on the city’s landmarks—recruited a raiding party of more than 100 vigilantes, including Tohono O’odham—Native Americans who were at war with the Apache—along with Mexican Americans and a handful of whites. On April 30, 1871, this group entered the encampment of the Pinal and Aravaipa Apache, indiscriminately killing about a hundred women, elders, and others, and driving a few survivors into the surrounding mountains. Some 30 children at the camp were captured to serve as slaves to Tucson’s wealthy.

The Camp Grant Massacre was celebrated in the local paper, and as the Apache and other tribes in the years that followed were forced into U.S. government-established reservations—which the Native Americans accurately described as concentration camps, noted Colwell—the incident remained a traumatic “phantom” memory whose sparse details were passed down through generations of Apache clans.

But today, Colwell emphasized, Native Americans are increasingly confronting their most wrenching historical moments in an attempt to heal, and they are pressing the nation to reckon with its troubling legacy. Colwell’s own work on the repatriation of cultural artifacts—which he wrote about in his book, Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture—suggests ways that tribes may help bring closure to the wounds of the past.

Museums possess millions of looted Native American items, from sacred religious objects to actual human scalps and skeletal remains. As a former senior curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, Colwell witnessed first hand the return of some of these to their places of origin.

In one case, he told students, a U.S. Army surgeon took the complete skull of a victim of the Camp Grant Massacre to the Smithsonian Institution, where it remained as a specimen for more than a century. When the Apache people learned of the skull and lobbied until it was returned under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act passed in 1990, they were finally able to mourn, said Colwell. “The act of reburying an ancestor, showing that care, allowed them to find a way to heal some of the wounds of history.”

As Dr. Davis noted, “The Apache people may have been removed from their land, but their descendants keep alive their culture and spirit of resistance into the 21st century.”