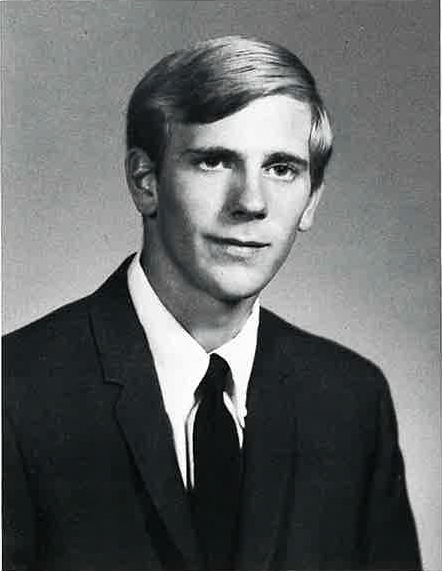

In many ways, the Colorado Academy that Keith Robinson ’67 experienced bears no resemblance to the CA of today.

In the mid-1960s, Robinson’s CA was an all-male boarding school, a place where he could attend classes during the year and pass the time at sleep-away summer camp.

Robinson’s CA was home to some legendary leaders: Head of School Chuck Froelicher, memorialized in the Froelicher Upper School; faculty member Ernest “Tap” Tapley, the first Chief Instructor and Staff Trainer at Colorado Outward Bound School; and Tom Fitzgerald, former teacher and Lower School Principal.

Robinson has never forgotten the November day in 1963 when Fitzgerald had to tell his students that his cousin, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, had just been shot in Dallas. He also remembers the ropes course that the Outward Bound pioneer Tapley set up between trees on campus. Robinson tried the ropes one day without supervision and discovered he could not fly, breaking both wrists in the process. When it came time to take his final history exam with Fitzgerald, a written test was out of the question.

“I had to do oral exams,” he says. “Believe me, my knees were shaking because I actually had to know something!”

Yes, it might seem this CA from 60 years ago has all but vanished. But what has not changed are the things that matter most. Today, students still make lifelong friends at CA, just as Robinson did. (He recently called one of his CA friends, Campbell Dalglish ’67, to wish him a happy 74th birthday.) Today, the environment that gave Robinson the chance to think outside the box still exists at CA. And, today, there are still teachers who change the direction of students’ lives with their curriculum and their ideas—just the way English teacher Francis Xavier Slevin did for Keith Robinson.

“He believed that a boy matured into manhood by experiencing life—not necessarily through reading books,” Robinson says. “After CA, I spent four years traveling in Europe, learning languages and history. But instead of reading about it, I was living it.”

The trip not taken

In 1967, when Robinson graduated from CA, he had no clear vision of what he would be doing with his life. He spent the summer as the only teenager working on an ore boat traversing the Great Lakes, before heading to Boston University where he had been recruited to play soccer.

A word about athletic recruitment in the 1960s. An enthusiastic athlete—he played soccer, basketball, and baseball at CA—Robinson had no plans for a collegiate athletic career until there came a knock on his father’s door one day. There stood a recruiter. Would he be interested in playing soccer at Boston U?

“I said yes, and it was all done,” Robinson recalls. “I had not even applied to go to school there.”

At Boston University, Robinson experienced success on the soccer pitch, but his life took a sharp turn one weekend when his roommate and two other friends from the dorm decided to make a trip to New York. He should come along, they said. But he said no. “I just didn’t feel good about it,” he remembers. The trip he did not take ended in a car accident, and his two friends were badly injured. His roommate died. Robinson never returned to the dorm room again, living off campus the rest of the year.

“At that time, there was no counseling, no one to talk to,” he says. “I remember going to class but not really being there. It was a rough year.”

At the end of his freshman year, he transferred to CU Boulder right at the height of Vietnam war protests. That is how he came to be sitting in Colorado with two CA classmates—the late Steve Underwood and Mike “Britt” Smith—on December 1, 1969, listening to the radio to hear the first draft lottery held since 1942. A low number meant he would likely be drafted and sent to Vietnam. His number was 323. (“I still play it in the lottery,” he says with a chuckle.)

That number gave Robinson freedom. He left school and followed what he calls “the river of life” wherever it took him. He worked in a pea cannery, as a baseball coach at a summer camp, and at a chicken factory in Maine. Then, one day, his uncle, a former dancer, asked him if he would be interested in taking a ballet class. And that is how, at the age of 22, Robinson donned tights and dance shoes for the first time and discovered what happens when passion and talent converge.

“That first day was really strange,” he says. “It just so happened I had a good body for classical dance. To hear positive reinforcement for something you are just starting is so nice, especially after years of bouncing around and not hearing much positive reinforcement.”

The trip taken

In dance, Robinson married his athleticism with an art. He was a natural. His teachers all assumed he had been dancing his entire life. With his uncle and his uncle’s wife, he founded the Robinson Ballet, a performance company and dance school, in Bangor, Maine. He met and married his wife, Maureen, who is also a dancer, and the two decided to try their luck with ballet in Europe. With their first audition, they landed positions in The Ballet Classique de Paris and toured Europe doing 92 performances of Swan Lake in 100 days.

Their next adventure led them to Greece, where they performed in Athens at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, which was built in 161 CE.

“In one of the scenes, I was lying on the dance floor, and I looked up and could see the Acropolis, and it was all lit up,” Robinson says. “I had a tingling rush of feeling run up and down my arms and legs. I was blown away that night.”

Robinson and his wife spent three years performing around Greece with the Balletto Athenon (The Athens Ballet). By then, they had been gone from the U.S. for four years and felt it was time to come home. They returned to Bangor where both taught ballet—Keith at the University of Maine Orono for 20 years. They both still teach, and both serve as artistic directors emeritus of Robinson Ballet, which has been in existence for almost 50 years. Every year for the past 30 years during the traditional December holiday season, Robinson has dusted off his costume and performed as Uncle Drosselmeyer, who creates magic throughout The Nutcracker. He plans to dance again this year “if I pass the audition.”

“In 1977, no one would have guessed that the Robinson Ballet would still be here, but we are,” Robinson says. “I am now dancing with the grandchildren of the people I danced with when we started!”

Keith and Maureen’s son, Ian, has followed in their footsteps and established a career as a dancer and teacher with an international reputation. “We were good, but Ian is in a different league,” Robinson says with justifiable pride. “He danced with Baryshnikov for two tours! He did it right.”

Though decades have passed since Robinson left CA, CA has not left him.

“There were fewer than 50 students in my graduation class,” he says. “With such a small class, there was really good communication between student and teacher. I have that same good one-on-one relationship with students when I teach dance, and I got a lot of that from CA.”

He also credits CA for encouraging him to “think outside the box” and to seek “opportunities that are available if you just have the willingness to take a chance and see where it leads.”

“We were not all model students; we made mistakes,” he says. “But CA allowed us to make mistakes and discover there will still be another day.”