I’ve been doing this a while, so I have seen some things come and go over the last 29 years. Schools, like businesses, are not immune to passing trends or fads. While the cost of these in business is a loss of revenue or a hit to the bottom line, educational missteps—the adoption of pedagogy that is trendy, but not effective—can undermine the long-term trajectory of a child, a truly devastating cost.

A great example is the educational “battle royale” during the 1970s between reading camps. One believed in phonics and the other in whole language instruction for helping young children learn to read. (Here comes a gross oversimplification, but I hope it helps to illustrate my point.) The former emphasized learning the connection between letters and sounds and the structure of words and reading. The latter argued that students learn to read naturally if exposed to rich language, books, and texts. In the ensuing decade whole districts and states took a stand behind one methodology or the other, often to the detriment of young people. Subsequent research supported—wait for it—a combination of the two approaches. It turns out that some readers will, with practice and support, get the hang of reading, while a significant proportion will not…unless they are provided with the building blocks of language—phonics.

In the phonics versus whole language debate, a key insight was missed. Students are not all the same. One size does not often (ever?!) fit all. Training teachers in a variety of pedagogical strategies and helping them to carefully track student progress and adjust their classroom practices to the needs of individuals and groups leads to progress over time. I think there is also an important message here for schools. In implementing change or choosing pedagogy, schools must first know their North Star: what is it that we really want students to learn? What skills are we going to prioritize? Then we must be thoughtful about the multiple pedagogies—the tools for helping students move forward—that we select.

It is also important to empower teachers, not school districts or states, to develop their skillsets through broad and deep professional development. Such continuing education becomes part of the whole faculty’s DNA, while allowing individual teachers to explore skills and practices they believe help them meet young people’s learning needs.

In my experience, Colorado Academy has done a good job of avoiding the “all-or-nothing” choices that some schools resort to. Instead, we continue to look over the horizon at what might be new best practices, while trusting some “tried and true” pedagogies that are neither new nor trendy, but are effective. When we look carefully at what individual students need and select learning tools thoughtfully, good things happen.

It is worth noting that this is part of why teaching is so intrinsically interesting AND challenging. What helps one child go deeper and learn more falls on deaf ears for the student next door. This means that picking and choosing among multiple effective strategies and practices is essential to students’ and schools’ success over time.

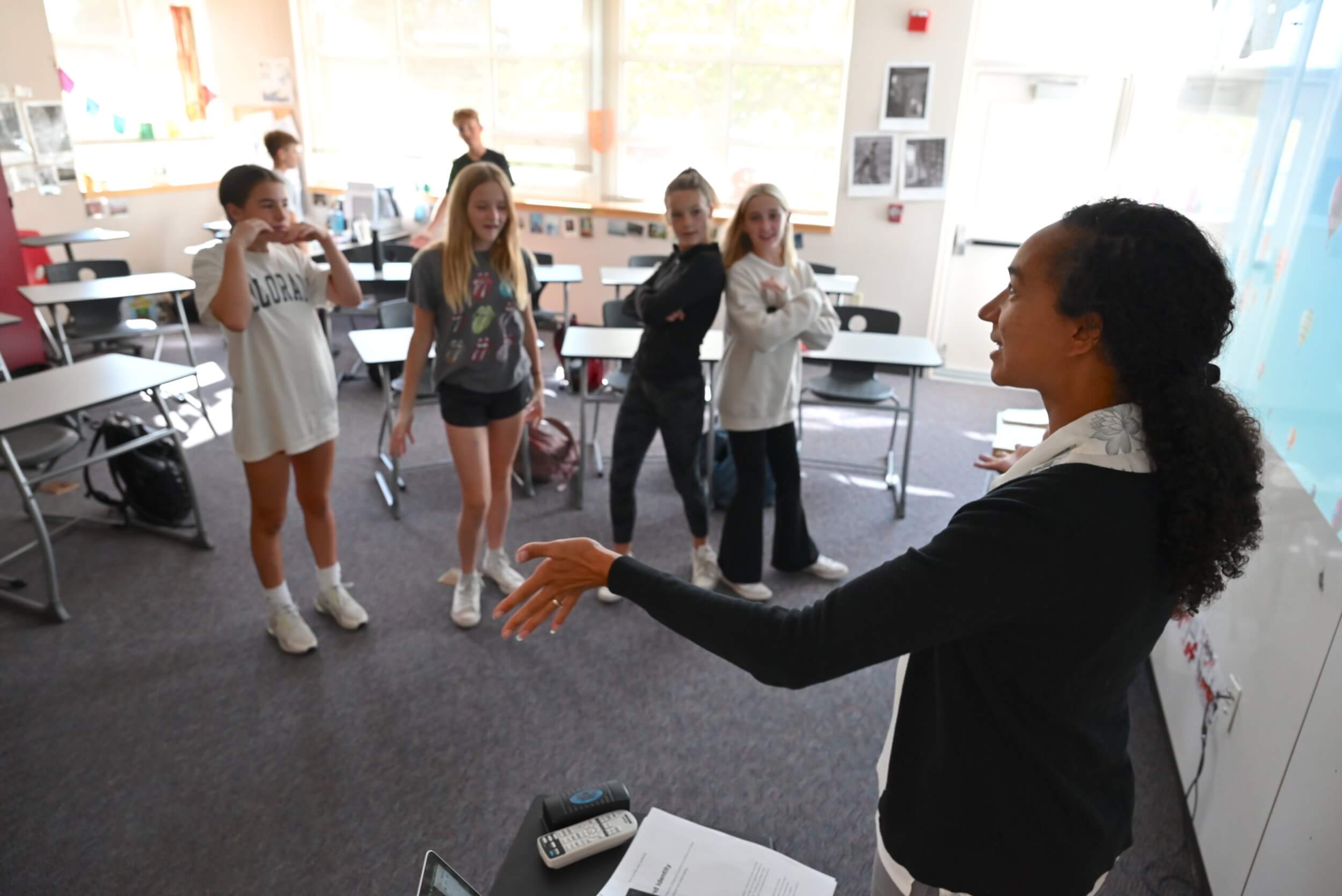

I have been lucky all these years to be surrounded by uncompromising teachers—teachers who look at teaching each student as both art and science; teachers with deep catalogs of “teacher tricks”—think rich and varied pedagogical knowledge—who are not satisfied until all students are making progress.

If I can be helpful in any way, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Best,

Bill