At Back-to-School Night this year I shared a few thoughts about the important insight that Adam Grant makes in his book, Think Again. In it, he argues for a reinterpretation of what is “smart” or “intelligent.” He encourages all of us to become more comfortable reassessing our beliefs based upon evolving evidence, to ensure that our conceptions of how the world works actually hold water.

His contention is that most people do not consistently do this kind of reflection and that we hold on to conceptions from long ago that no longer serve us—or worse, have been contradicted by evolving evidence. His hope is that we will ALL be more willing to examine what we believe to be true.

One of the things that strikes me about Grant’s book is his hope that we REVEL—yes, revel—in discovering when we are wrong or when a belief, small or large, is proven to be false. Reveling may be a bit of a reach, at least in my experience, but the point he makes is nonetheless an important one. It is only when we are willing to update our beliefs that we move closer to a more complete understanding of what makes the world go round.

At Colorado Academy, we are NOT in the game of telling students what to believe, but are very invested in helping students develop the tools to investigate their beliefs, ideas, and the world around them. I’ve been on the planet for a while, longer than many, not as long as some, and in my experience, we are living in an increasingly polarized climate. This makes it even more important that we help young people explore different ways to understand the ideas and perspectives that surround them.

Equally important is our ability to help each child understand that it is in their power to move from one best understanding to another based upon evidence. This openness to growth and change is central to education—as is the willingness to look anew at what we think we already understand.

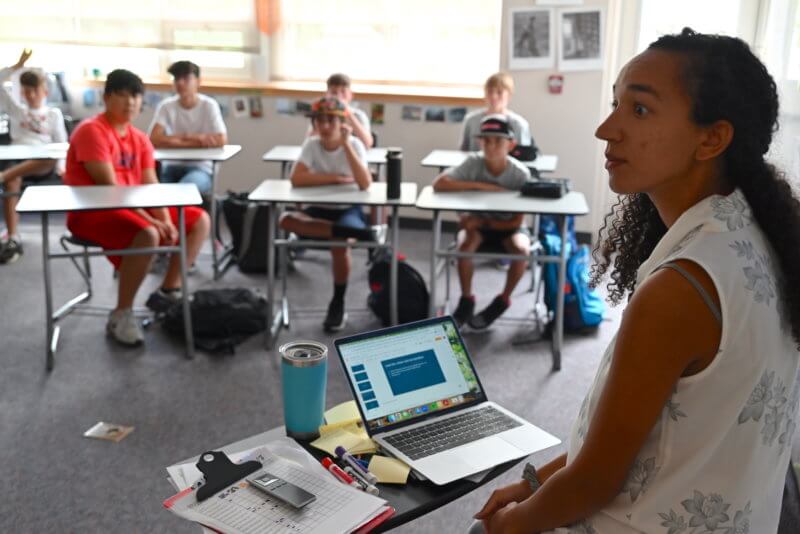

In the Middle School, the emphasis on critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration is a springboard to the iterative give-and-take of thinking through ideas, comparing what we think might be right to the actual evidence, and doing this again as our ideas about math, science, literature, history, and world language evolve.

A great example of the kind of thinking we hope young people will encounter happens in our Seventh Grade Critical Thinking social studies class. Students experience successive challenges which invite them to consider problems and come up with solutions. In the process, they learn to try on different ideas, evaluate whether they move the needle forward, and then return to the beginning to develop a new tactic or strategy. Another unit in the class asks students to debate either side of a complex issue, based upon the flip of a coin. This demands significant research and study, as well as the ability to see an idea from all sides, not just two.

We do not want students in Eighth Grade to think that they have reached the conclusion of their thinking evolution—that the ideas they hold as Eighth Graders are the ones they should hold at eighty. Instead—and this is Grant’s great insight—we want them to have the habit of curiosity (see CA’s mission statement!) and the tools to explore their world, hungrily looking for ideas that help them explain what it is they find around them.