Teaching Middle School Civics during a presidential election year is no small challenge. Teaching it during this particular election year, 2024, ratchets up the difficulty level even higher, as families everywhere weigh two dramatically different visions for the United States, and even Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Graders—though not yet voters—try on various political viewpoints to see what fits.

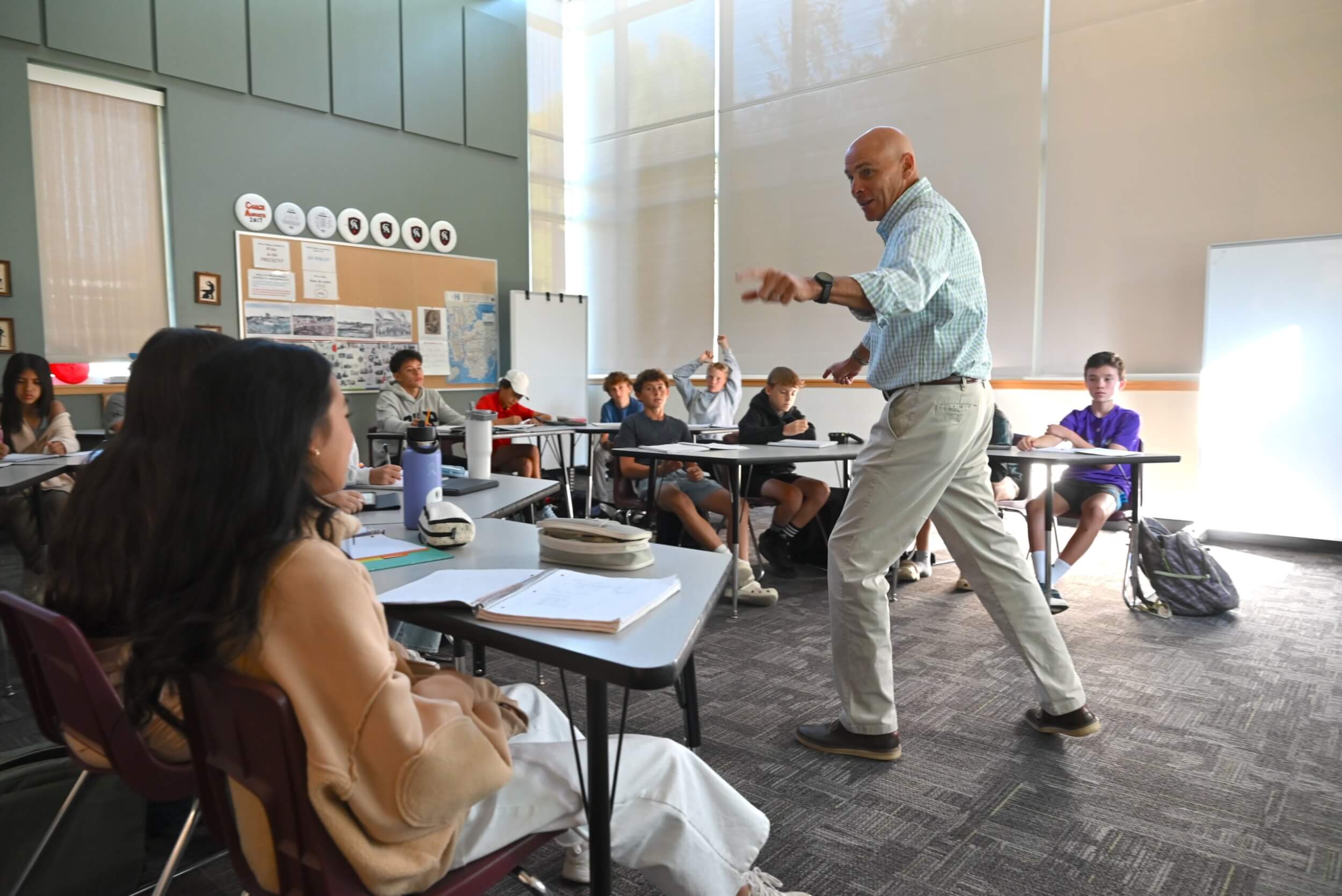

“It’s hard not voicing an opinion,” says Middle School social studies and English Preceptor Eric Augustin. “When we’re with our students, we work intentionally to stay away from making political arguments one way or the other”—though achieving perfect neutrality is probably an impossible task, he acknowledges.

At the same time, he notes, “We also have a responsibility to explain, in factual and historical terms, why some of the most extreme ideas we’re hearing today might not jibe with the principles on which this country was founded.”

Teachers may well enter their classrooms carrying with them political perspectives from all across the spectrum—and indeed, it’s almost inevitable that their students will pick up on these—but, “There are things that are not a matter of opinion,” says Middle School social studies and Spanish Preceptor Sara Monterroso. “The concept of the ‘common good’ and the limited power vested in each of the three branches of government—these are not partisan issues; they are enshrined in the Constitution.”

At Colorado Academy, the Eighth Grade course simply titled “Civics” is in some ways a capstone among capstones. During their final year in the Middle School, students complete numerous cross-disciplinary projects, solo and in groups, to demonstrate what they’ve learned about critical thinking, creativity, and problem solving; these include everything from authoring children’s literature to designing an escape room, to proposing changes to campus architecture and school rules. In social studies, students engage with difficult, real-world questions about their country’s past and present that prepare them for high school and life beyond, when they will inherit an increasingly complex society in which the role of government in the lives of its citizens is more contested than ever.

The rich and challenging Eighth Grade social studies curriculum they study flows from everything that precedes it. In Sixth Grade, students delve into the topics of migration and immigration—metaphors, in a way, for their own arrival in Middle School, where they intuit, and sometimes flout, the norms and expectations of a new community. Seventh Graders investigate identity’s role in society; in the culminating debate unit, they argue opposing ideas about how individuals exist within various constructs not of their own making, and what that means for social change.

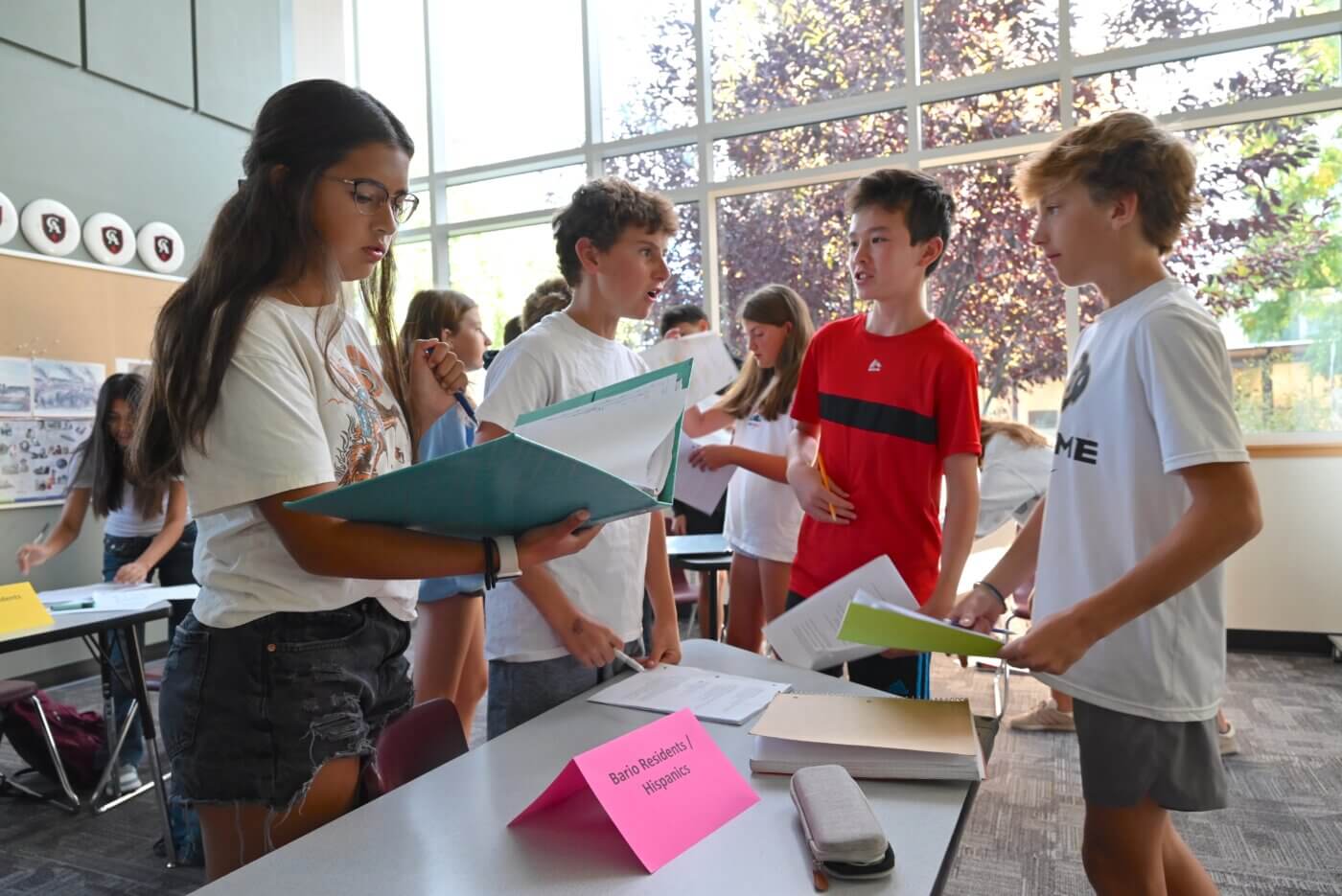

In Eighth Grade, explains Augustin, students learn that changing the world goes beyond debating who is right or wrong—it requires true deliberation. “You can demonstrate all you want in support of civil rights, but until you change the law, nothing fundamentally shifts in the way society functions. The ‘right’ answer to the challenges we face is the one that grows out of the knowledge we gain when all voices are heard.”

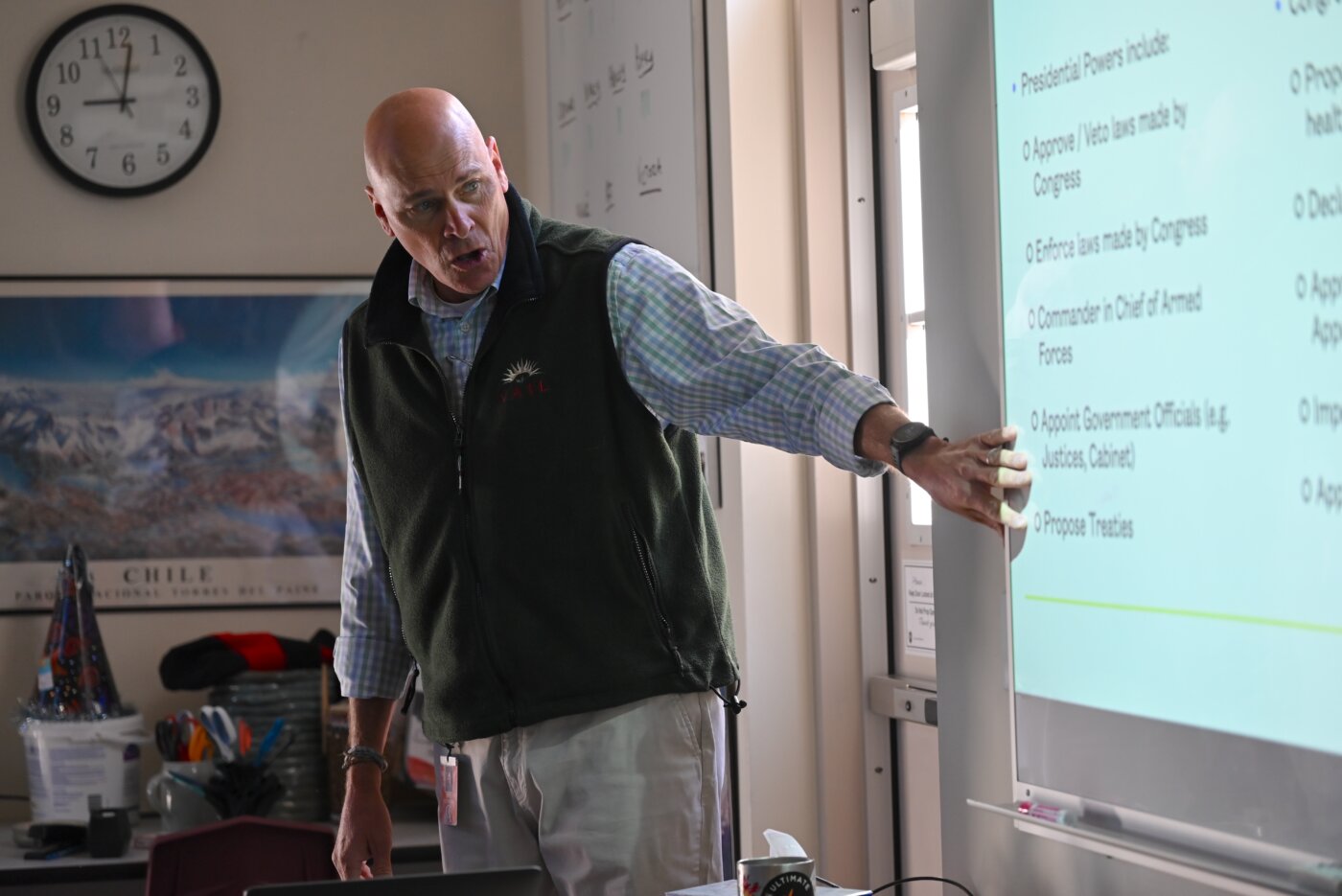

Discussing the importance of laws means looking closely at the Constitution—its origins and purpose—as well as the three-branch structure of the U.S. government, with its all-important separation of powers. “Why was the Constitution written this way, and why does our government look like this?” are guiding questions, as students trace a lineage that goes back to the British system of Parliament and King, while departing significantly from it.

Eighth Graders gain context for understanding the idea of checks and balances and the formulation of the Electoral College—a system that’s poorly understood by most Americans today, Augustin points out. They closely examine the works of thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose philosophies pertaining to a “State of Nature,” the common good, and “consent of the governed” heavily influenced the framers of the Constitution.

Being able to reference these foundational ideas, says English and social studies instructor Liz Estacio, is central in enabling students to think critically about the role and actions of government and a citizenry. “They’re not necessarily going to memorize every Article and Amendment in order, but they can be equipped with the knowledge of what informed them and be prepared to question what they’re being told today—by the media, TikTok, or whatever it may be—in terms of what the framers intended,” Estacio insists.

“We want our students to understand that our government was designed to force difficult conversations, to force compromise,” adds Augustin. “Compromise is the definition of democracy; change should be slow, moderate, and deliberate. Unfortunately, the American people by and large do not want compromise.”

As Monterroso elaborates, the United States is a highly individualistic country—“perhaps the most individualistic in the world. But the framers of our Constitution recognized that we’re not just individuals; we are a polis, a people, with rights and responsibilities to benefit all. Our government and our laws need to represent all people, all voices, in order for our country to function the way it was envisioned. And hopefully, by the end of the school year, they’ll see how that famous phrase, ‘We the people,’ isn’t really so separate from our government and our nation. They are one and the same.”

Into the weeds

During an election year, when the rhetoric of national and local political candidates ramps up to its peak in the early fall, CA’s social studies teachers must challenge their students unusually early in the school year to wade into the weeds of the executive branch of government: What actually is the role of the President? “Presidents don’t make laws—that’s the role of the legislative branch,” says Monterroso.

“We pay all of this attention to what presidential candidates are promising us,” Augustin goes on, “yet the President’s role is literally to preside; there are these state congressional elections going on at the same time. So what values do we want in our leaders—not just the President, but our representatives, as well?”

Estacio adds, “There’s a lot of conversation about all the dire things that could come to pass if one candidate or the other wins. In class, we have students step back and ask, when one candidate says they’re going to do something drastic to change the government or the law, what does that actually mean? Is it even possible or legal? What kind of Congressional support would there be? And what about the budget implications—who’s going to pay for it?”

Amid the fear and anxiety stoked by various media outlets, Eighth Grade Civics is a place where optimism rules the day. “We don’t want to create more pessimism out there,” explains Augustin. “We want to educate people who not only have hope in our system, but also have an understanding of how it works and why it works, so that they can then go and be better citizens than maybe we adults are.”

The American system of government was specifically designed to prevent the arbitrary use of national power, concentrated wealth, and other domestic forces the framers believed caused turmoil throughout history, the Eighth Grade teachers know. “This is why presidential powers are limited; this is why Congress was organized so it cannot come to agreements easily,” Monterroso makes clear. “This is why we have a federal system where states possess so much of their own authority.”

But when Augustin asks his students how many voters they think are likely to read through the thick information pamphlet that arrives before every Election Day, laying out the text and potential implications of various state ballot measures, they are surprised by their own immediate intuition: probably very few. And when they learn that barely more than half of eligible adults actually cast their vote for president, their astonishment grows.

Citizenship is an active role, these teachers try to impress upon their students. “And if you don’t take that active role, then somebody else will, and that may not be in your best interests,” notes Estacio.

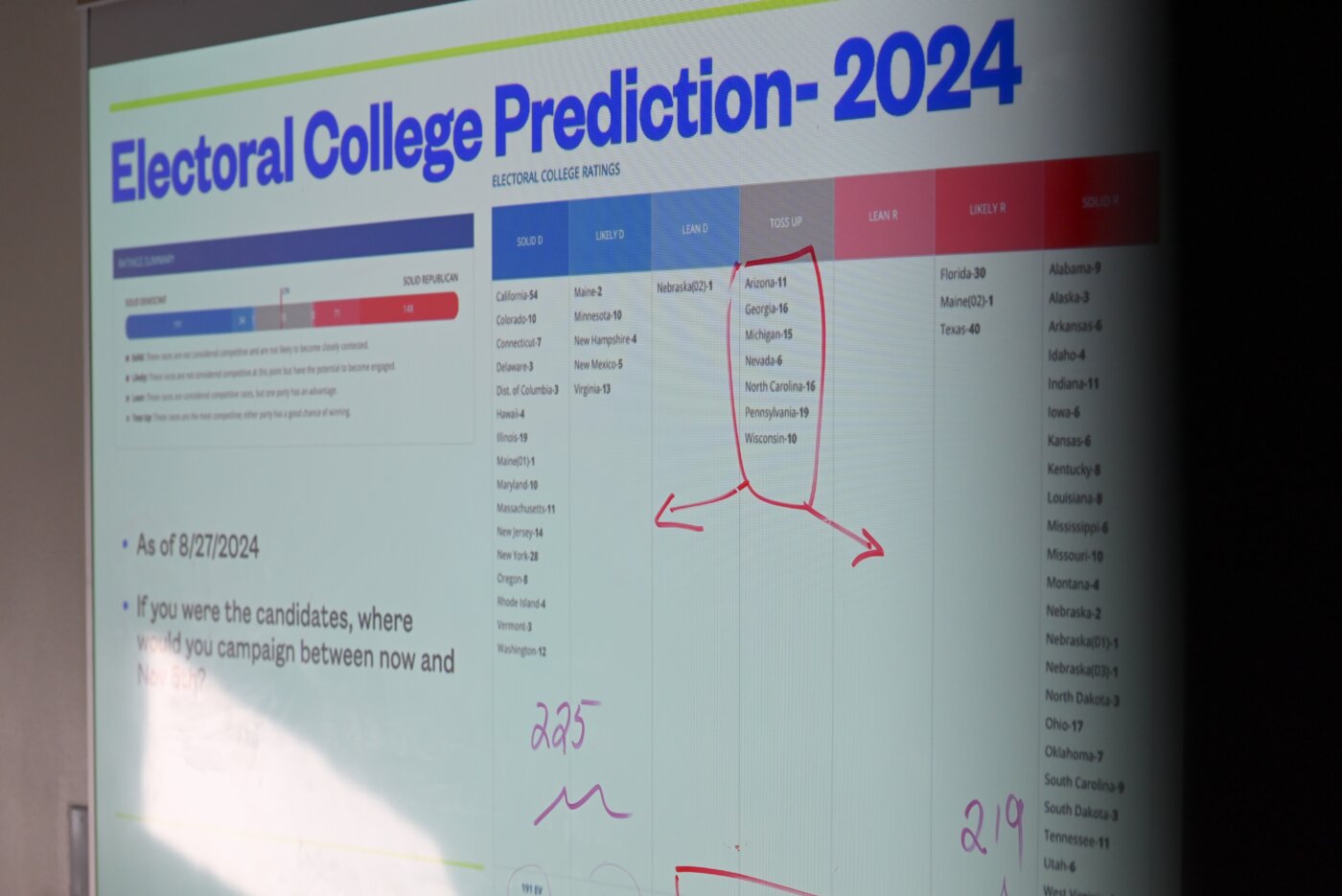

As Election Day looms closer, and news organizations obsessively speculate about potential Electoral College totals for each candidate, students delve into perhaps two of the biggest mysteries of any election year: How does the Electoral College system work, and why was it devised?

Eighth Graders quickly learn that, rather than simply a cumbersome and archaic method for electing the U.S. President and Vice President, the Electoral College represents a painstaking compromise by the Constitution’s framers, who attempted to account for the fact that the popular vote could be easily swayed by local factors, corruption, and fraud, while mitigating both the threat of a too-strong executive and the danger of Congress or other influential groups controlling the Presidency.

To the question, what is most interesting about teaching Civics during a presidential election year, “The boring but most profound answer is the Electoral College,” states Monterroso. “Why do these votes fall the way they do? Why not just have a popular election? What was on the minds of the framers when they wrote Article II,” which describes the powers of the President and the processes for electing and removing the nation’s chief executive.

That this 235-year-old system for orchestrating the ascension and smooth succession of power is practically all anyone can talk about for a couple of months in the fall, every four years, is a boon for CA’s Eighth Grade social studies teachers. “Something big is happening that we all have a stake in, and civics is what we’re all discussing at the dinner table,” Augustin observes.

It is the definition of a teachable moment.

Vision and its imperfections

The Constitution of the United States may be the oldest and longest-standing written and codified national constitution in force in the world, but that doesn’t mean it—or its framers’ intentions—were perfect. Argues Monterroso, “Part of what we teach in Civics is that the uniquely American notions of ‘pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps’ or ‘all men are created equal’ are mythologies when you look at the actual history of the country.” Yet the nation’s founders and the framers of its most important guiding document were nonetheless able to cement an enduring ideal that has stood the test of time.

“How has our Constitution managed to weather all of the storms, the change and growth of the country as well as what it means to be an American, but remain fundamentally intact, with its amazingly adaptable Bill of Rights?” Monterroso asks. “There was real vision in its creation, and since that time, we’ve made steady, though slow, progress toward making those mythologies increasingly true for all Americans.”

Relatively speaking, Augustin points out, “We are a young country; we are still an experiment to some degree.” When people complain that our system is broken and should be thrown out, he continues, “The truth is that the democratic system is working as it’s supposed to; it is responding to the people, who instead of seeking compromise and the common good, seem bent on pursuing agreement at all costs.”

“Our country feels more tribal than at any other point in history,” reflects Estacio. “We all crave what benefits our own small universe the most—which isn’t surprising, given the country’s underpinnings in the ideas of freedom and self-determination. But with more voices comes more division.”

One of the goals of Eighth Grade Civics is de-emphasizing the divisiveness, the teachers say.

“Fundamentally we all want the same things,” Augustin explains. “We all want safety. We all want a strong economy. I talk often with my students about alignment, about how we may not agree about every detail, but deep down we are aligned on the core issues.”

Whether the topic is gun control or abortion, he continues, “If I hear students walking out of my classroom saying, ‘I hadn’t thought of it that way,’ then I know I’ve done my job.”

At the fall Back-to-School Night, Monterroso tells the parents and guardians visiting her classroom, “Your kids should be questioning you; they should be questioning me. It means they’re thinking, they’re dissecting everything that they thought they understood and putting it back together in a way that aligns with their values. If your kids finish the year with more questions than they started it with, then it’s been a good year.”