Every Fall, Admission Officers at Colorado Academy hear a familiar question from prospective families.

“How many AP classes does CA offer?”

The answer to the question is easy: 17.

But Director of Admission and Financial Aid Catherine Laskey hopes applicants will also pose a different question. “Ask us about Honors Electives that allow students to brainstorm, analyze, discuss, and apply what they’ve learned on a particular topic—in essence, courses where students can take a deep dive into a faculty member’s area of expertise, making the learning relevant and engaging,” she says.

CA Upper School offers more than 40 Honors Electives in subjects as varied as “The War on Terror,” “Contemporary Literature of the Middle East,” and “Statistics and Data Science.” Many Juniors and Seniors take Honors Electives in addition to AP courses. They are seeking balance in their education, knowing that both types of courses will be of interest to colleges when they apply and also will benefit their overall education and ability to think critically about issues as college students and adults.

While AP test scores may indicate mastery of subject matter to a college, students who take CA Honors classes feel like they have experienced a college course while still in high school. “Nearly all secondary schools in the Denver metro area offer either AP classes or an IB curriculum,” says Upper School Principal Dr. Jon Vogels. “CA is proud to also offer in-depth discussion-based Honors Electives where students have the opportunity to sharpen their reasoning, inquiry, conceptualizing, problem-solving, open-mindedness, and writing. These types of courses are typically only found at the college level.”

To offer a sense of how Honors Elective courses distinguish CA, we spent time observing four different courses, talking to students and teachers.

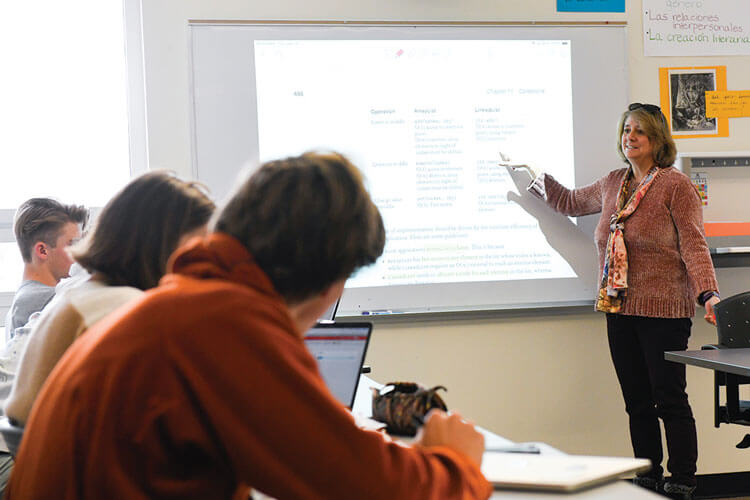

Honors Elective: Gender Studies

“I don’t think I could ever be a mom!” This declaration—which comes from a male Senior as soon as he drops his backpack and sinks into this seat—starts an enthusiastic discussion before Gender Studies teacher Elissa Wolf-Tinsman has even begun class.

Wolf-Tinsman goes with the flow established by the lead-off remark. “Why not?” she asks. And that’s all it takes for her class to swing into a free-ranging discussion of a wide variety of ideas: How has the role of motherhood changed through history? How do Instagram influencers lead mothers to feel guilty about their parenting? What did Freud say about the best way to be a mother? How did feminist Betty Friedan give voice to a different view of a woman’s role as a mother?

Every single member of the class, which is sitting in a circle, is intensely engaged. Wolf-Tinsman blends into the circle, prompting the discussion with quiet questions. The good-sized group is evenly divided between males and females, a fact that delights Wolf-Tinsman. As a student, she studied Women’s History and watched as the field evolved into Gender Studies, which she believes is more inclusive. “Boys are enrolling in this class now because they see it as not just about girls and women,” she says. “It’s about humans and how we move forward as a society understanding each other better.”

The students come to that new understanding through a rigorous selection of readings, many of which have been published in the past two years. As times change, Wolf-Tinsman can tailor the reading to societal issues, something students really like. “I took the class because it is relevant to today’s society, like the #MeToo movement, gender discrimination in employment, stereotypes about gender in school and at home,” says Junior Henry Chesley-Vogels. “I wanted to have thought-provoking discussions that allow me to look at gender with a new lens.”

The class discussion lands on a new question: “What is the ideal mother?” This prompts a healthy exchange of ideas about the pressure mothers might feel to be perfect. “A mom should take time for herself sometimes,” observes one student. Wolf-Tinsman challenges the class. “Are dads judged on the same criteria as moms?” More discussion follows. Wolf-Tinsman sits back and lets the students direct the debate.

“They all come in with some preconceived notions about gender and power dynamics in society, and they learn there may be greater nuance than they realized,” she says. “They develop critical thinking, tackling challenging topics, listening to different viewpoints, and responding with mutual respect.”

“This course prepares you for college discussions where you will be studying

and discussing sensitive material,” adds Chesley-Vogels.

Like many in the Honors class, he is also taking AP courses, which he finds equally rigorous but in a different way. “The AP test is coming in May, so it’s important to stick to the text on a schedule,” he says. “The Honors Elective gives me more opportunity to delve deeply into a single topic for a longer period of time.”

Wolf-Tinsman created the course with fellow Gender Studies teacher Emily Perez, and the two teachers collaborate to improve the curriculum each year. The culminating project in the course is a lengthy, college-level research paper on a topic chosen by each student, complete with thesis, outline, sources, rough draft, revisions, and final product. “This course has really elevated my writing skills,” Chesley-Vogels says. “I’m more of a math and science guy, but I never loved writing more than doing this paper, because I got to write about a topic that was important to me.”

The class ends with a discussion about the gender pay gap, and now Wolf-Tinsman challenges the students to break into small groups and come back to the larger group with solutions. “Your generation is moving into the professional workforce,” she tells them. “How will you address this issue?” They return with truly creative ideas. Wolf-Tinsman smiles. “I love this class,” she says. “I so appreciate their honesty.”

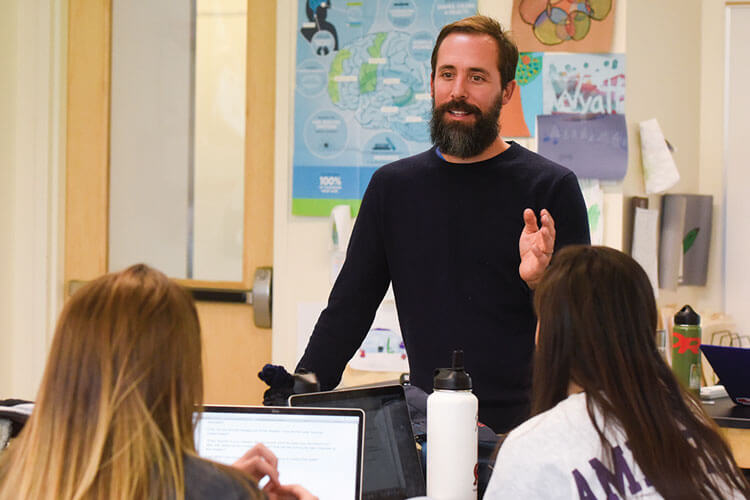

Honors Elective: Literature of the Apocalypse

English teacher Tom Thorpe would be the first to acknowledge that the Honors Elective course “Literature of the Apocalypse” deals with dark themes. The readings include Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Road, Tom Perrotta’s The Leftovers, as well as writing from Jewish and Christian apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic tradition. “The course asks that we think broadly about the human condition,” Thorpe says. “What makes us obsessed with the idea of ‘The End’?”

The topic may seem an unlikely choice for students in Grades 11 and 12, but there are no empty seats in the classroom. Junior Elsa Mushkin explains it simply. “We tend to run away from dark things,” she says. “But in our culture, it’s important to face the darkness, and you feel more protected doing it through literature.”

“I am actually less frightened of an apocalyptic event after taking the course,” says Junior Makayla Martinez. “This class asks you to think about the big questions—if it happened, what would it be, how would we react, how would society continue?”

Thorpe maintains that students in Honors Elective Courses have taken an important first step in their preparation for college simply by enrolling. “In college, they will be presented with many options for elective courses with a huge amount of freedom to choose,” he says. “How are they going to figure out what courses to take unless they have had some practice in researching a course? That’s what our Grades 11 and 12 electives allow them to do—practice choosing.”

In one way, the course is very different from a college course. At the beginning, Thorpe alerts parents to the dark themes that students will confront and suggests that their readings may provide opportunity for conversations at home. “The literature we tackle prompts profound discussions about difficult topics,” Thorpe says. “We do it with safety nets and scaffolding around them, always remembering this is literature created from someone’s imagination.”

In the classroom, Thorpe breaks the students into small groups and assigns quotes from The Road to each group. Students make a beeline for someone who has a quote that interests them. “Perhaps in the world’s destruction, it would be possible at last to see how it was made.” McCarthy’s words spark passionate discussion. What does the author mean? What are the implications of these words for the characters in the context of a post-apocalyptic world? The discussion is intense and driven by the students as they move around the room.

“They are learning how to think and how to think about their thinking,” Thorpe says. “Their responsibility to interact with the material and each other prepares them to take on the next hard text and learn how to deal with the ambiguity of complicated ideas and writing.”

The students embrace the challenge. “This course tests your maturity,” says Senior Lexi Howard. “As we get older, it will be our responsibility to address the problems in the world, so it feels safe to start by reading and discussing a book you know isn’t real.”

“I really like that we are writing on a different topic every week in this course, sharing our ideas,” adds Senior Nate Kay. “This course prepares you for college, because you cannot get through with rote memorization. You are forced to pay attention to the material and do your own analysis.”

By the end of the class, Thorpe gives the students his own thoughts to consider as they go into a bigger world. “The Road is ultimately about morality,” he says. “In an extreme environment, people learn to what extent their humanity can be pushed. What instinct is stronger? Being moral or surviving?”

Honors Elective: Advanced Computer Science: Data Structures

“It took me 25 hours to create this assignment,” teacher Kimberly Jans announces at the beginning of her class in Advanced Computer Science: Data Structures. The eight students in the class are riveted as she plays the results of her work, a programming assignment requiring students to add visual and audible elements to a sorting algorithm and create a unique animation. When she finishes, the students applaud enthusiastically.

This is not a class for novices, as indicated by the textbook: Java Methods: Object-oriented Programming and Data Structures. The students have already taken AP Computer Science, some of them as Sophomores, as a prerequisite for the course. “They picked up great skills in AP, and the work piqued their interest in computer science,” Jans says. “That’s what brings them to this class.”

This Honors Elective is the equivalent of a college freshman’s second semester of computer science. “The course allows you to be creative in the subject,” explains Senior George Davis. “You apply the knowledge from year to year, moving to a higher level and expanding what you can accomplish.”

As Jans leads the group in their understanding of the language of searching and sorting data, the students bounce ideas off each other and off their teacher with ease and authentic determination to solve the problems. Jans keeps the discussion about sorting algorithms and analyzing their complexity moving with prompts and encouragement: How do we take objects and compare them in Java? Is it worth it to do a binary search? Don’t worry, you will understand this algorithm when we get done!

“I love this class,” Jans says, who has been teaching computer science for 30 years. “The students are here because they also love computer science, and they want to dig deeper. Even though we have a set curriculum, we have the flexibility to take time out to do projects that interest the students.”

Seniors Walt Jones and Tyler Wolf Williams are a good example of students pursuing an interest. They have just taken two weeks to transform the classic board game “Battleship,” coding it so that a computer-based artificial intelligence plays against another computer. “Ms. Jans says, ‘Is there any interest in doing this?’ and if there is, she creates the curriculum,” Jones explains. “You are learning because you are curious about the content. The next thing I want to learn more about is quantum computing encryption.”

Senior Sammy Moore-Thomson sums up student sentiment. “In this class, we have a say in deciding what we are learning.”

Studying computer science with Jans is an aerobic exercise. By the middle of the class, she has everyone out of their chair, and they are engaged in human sorting, acting out an algorithm in groups around the room. It’s tough work, calling for engaged brains. No one is more engaged than Jans, and no one quits. And that may be the ultimate learning experience in this course.

“You feel like you are banging your head against a wall, but you don’t let go, and then finally, the code works, and you have something solved,” Jans says. “The feedback is right there before your eyes, and you feel like you have knocked it out of the park.”

Honors Elective: Environmental Chemistry

In Environmental Chemistry, teacher David Frankel makes sure that nothing happens at the beginning of class. In fact, he guarantees it by setting a timer. For two minutes, the classroom is silent as everyone practices Mindfulness, shutting out the distractions of the day. Some students’ heads tilt downward, some eyes close. It is how Frankel starts all of his classes. “This helps all of us focus and be present in the moment,” he says. “Students know there is a predetermined way every class starts. It’s our routine.”

But when the mindfulness minutes end, the class explodes with energy. Frankel doesn’t say much beyond, “Let’s get to it,” and everyone moves to the lab bench to grab beakers, pipettes, testing strips, and water samples. They know their goal. They are safeguarding Colorado’s water.

The previous day, the students traveled by bus to Bear Creek to take water samples. Now they are testing the water for pH, alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, and hardness. They will send their results to River Watch, a statewide citizen science network of more than 200 volunteer groups with this motto: “Real People doing Real Science for a Real Purpose.” River Watch is supported by Colorado Parks and Wildlife in its mission to gather high-quality data, which will influence

the state’s decision-making about preserving and restoring the condition

of Colorado’s water.

The students test the water they gathered with a sense of higher purpose. What they learn matters in the state they inhabit.

“I’m passionate about our environment, and I want students to be more aware of their impact on the environment,” Frankel says. “I want to make sure they understand the science of what’s happening around them—what happens when we put salt on the roads, when we look up and see a brown cloud around Denver, when we have ozone warnings.”

In this yearlong course, students study water quality, air quality, toxicology, and the science of climate change. Senior Paul Chandler says students in the class are “freed from a textbook,” because Frankel asks them to find readings on the topics that interest them and share what they learn with the entire class.

The students break into small groups to discuss their recent reading. One group is talking about the carcinogen chromium-6 made famous by the movie Erin Brockovich that is still present in the water of Phoenix, Arizona. One group is discussing a recent Supreme Court case deciding whether a wastewater treatment plant in Hawaii should be subject to anti-pollution provisions in the 1972 Clean Water Act. Another group is discussing lead leaching into the water in Newark, N.J., and the failure of filters to remove it.

In a discussion with the class at large, Senior Holden Ryu connects the New Jersey water to Flint, Michigan and talks with authority about how heavy metals cross the blood-brain barrier and cause developmental delays in children. “Lead is in so many things; this is not a simple issue,” he observes. “You have to overhaul our entire infrastructure, costing billions.”

Asked why they chose an Honors Elective, the students have varying answers. “The subject matter is advanced,” says Senior Jasmine Moore, “and you have so much legroom to explore.”

“An Honors Class has an approach individualized for each student,” says Senior Ella Greene.

“The teachers who choose to lead Honors classes are passionate about what they are teaching,” adds Senior Jake Donaldson-Reid. “They are teaching what they love.”

Frankel would agree. He likes to talk about the “Aha moments,” when students make changes in their lives based on what they are learning—adding a second recycling bin at home or turning off the lights when they leave a room. “They are finding their own carbon footprint and realizing there are things they can do to minimize it,” he says. “Hearing a student say that this should be a required course, because they are all learning about how they impact their environment—that’s when I know the course is a success.”