There is just something magic about making fire—especially when you do it without a match, or a lighter, or any modern fire-making aids.

Just ask Jessica Ohly’s Fifth Grade class at Colorado Academy, as they watch Tyson Hughes, Education Manager from Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, work his spindle stick back and forth, faster and faster, hoping for a few embers to drop onto his hearth board, where he can then transfer them to a nest filled with dry cattails and see flames rise.

“You got this,” one student called. The rest focus, mesmerized, as a puff of smoke appears from the spindle.

“Good lesson here,” Hughes says. “Where there is smoke, there is not always fire.”

It takes a communal effort, with help from fellow Crow Canyon Educator Becky Hammond and Colorado Academy Lower School science teacher Diane Simmons. When the flames finally appear, the Fifth Graders erupt into spontaneous applause.

This is just one lesson in their day-long immersion into the lives of Ancestral Puebloan people. Hughes puts the fire-making lesson into context with one question to the students: “Why do people need fire?”

The CA students are well-prepared, and their answers tumble out. “They need it to keep warm…they need it to boil water…if they want to melt something to make a new shape, they need fire…and they need it to have light, because they didn’t have electricity.”

“Fire and humans, we are dependent on each other,” Hughes says. The Fifth Graders are ready to extinguish the fire, but Hammond reminds them that for Puebloan people, fire is sacred—you don’t put it out, you let it burn out—a new concept for students.

“It is always important to learn about other cultures,” says Simmons. “When these experts from Crow Canyon talk with them, they are so excited to meet them and learn from them.”

The Crow Canyon experience

For nearly 20 years, CA Fifth Graders have traveled to the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center near Mesa Verde for a week in the spring. They visit Mesa Verde National Park and Hovenweep National Monument to learn about the life of Ancestral Puebloans, and they are guided by experts from Crow Canyon. But COVID-19 restrictions canceled the travel plans again this year.

If students could not make the journey to meet the experts, the experts could come to them.

Hughes and Hammond came to CA for three days, spending one day with each Fifth Grade class, introducing them to hands-on experiences that take them back to the time of Ancestral Puebloan peoples.

In science and social studies, students prepared for the visit by studying the periods of human development in North America, starting with Paleo Indian, and moving through Archaic, Basketmaker, Pueblo I, II, III, Post-migration, and Modern Pueblo.

“They are the original people who lived in Colorado, and we can learn from them,” says Fifth Grader Ella Bilir. “It is good to know how our culture started.”

“We give them a head start before they have this experience,” adds Simmons. “The Crow Canyon staff loves teaching our students because they can take them to a deeper understanding.”

Archaeologists and linguists without leaving the classroom

Ms. Grantham’s class is divided into small groups studying all sorts of items: a skull, a cob of corn, a basket, fire-making materials, a spear, a piece of turquoise. They haven’t left their classroom, but they are all budding archaeologists.

At Hughes’s direction, they are observing the evidence and making inferences, putting each group of items in the correct chronological order dating back to Paleo Indian. They are essentially excavating a dig on paper.

“Tyson brings the experience of an archaeologist to this exercise,” Simmons says. “He is an expert at what he is teaching.”

Fifth Grader Nico Lish is excited about his discoveries. “We saw a mug and that would have only appeared in the Pueblo III period,” he says. “We also saw seeds for sunflowers, and we think that belongs in Pueblo III.”

“It is all interesting,” adds his classmate Darcy Simon. “It is important to understand Colorado’s history and the Southwest, so that people in the future will know what happened in the distant past.”

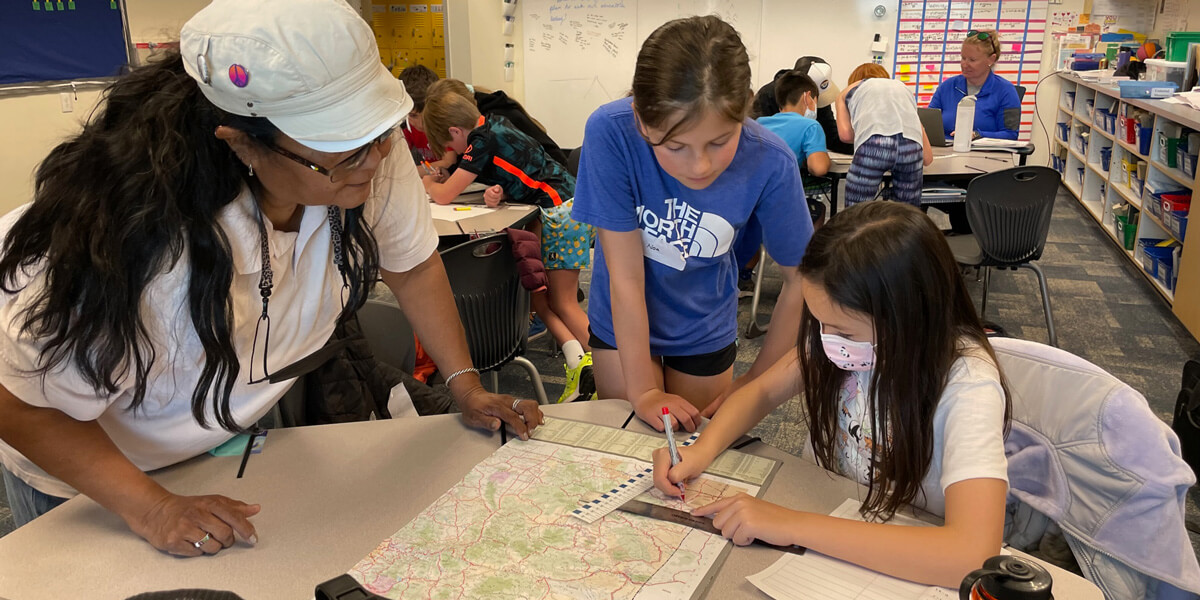

At another point in the day, Hammond leads an exercise that has students in small groups poring over maps of Colorado, looking for 17 Ute names in the state. They triangulate an area of the map, search for the names, and list them.

Ella is surprised. “I had no idea that Colorado had that many Ute names!” she says. “And they are interesting words.”

At the end of the exercise, Hammond lists the words on the board and tells students the meaning. “Saguache” means “a blue green place,” she tells the students. “Tawoac” means “Thank you.” Pagosa means “boiling water.” “Hovenweep” means “dry creek bed.” “Weminuche means “people who keep the old ways.” Fifth Graders now connect a place they may have visited with a people that once lived there and named it.

When Hammond tells students these meanings, they hang on her every word. She is a member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, lives on the reservation, and she often references her family’s history.

“I don’t know how many of our students have met a Ute Mountain Ute Indian,” says Simmons. “She is an authentic voice, and she commands respect.”

Cordage, jewelry, games, and hunting

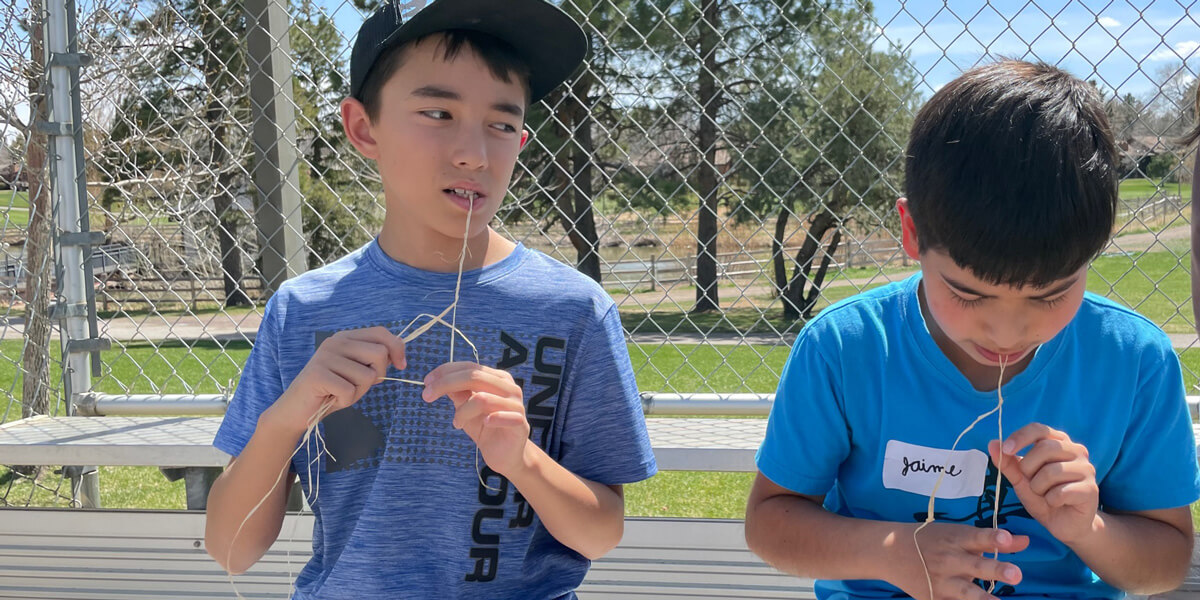

“What did ancestral people use to make rope?” Hughes asks the Fifth Graders.

Again, they are ready with an answer: “Natural fibers, like yucca!”

Today, students will make their own string—cordage—using strands from a raffia palm.

“This is really satisfying,” says Ollie Dias. “You twist and you loop, and as it knots together, you feel like you are accomplishing something.”

Hughes turns the discussion to the ways Ancestral Puebloan people created jewelry. Using small chunks of pipestone (catlinite) and water, students mold the stone into decorative pieces.

Then they use a pump drill to make a hole in the stone, so they can string their cordage through it. Suddenly, they have created an original piece of jewelry.

What better way to celebrate their creative skills than with a Puebloan game, the hoop and stick? Divided into two relay teams, the students quickly master a simple concept—scoop the hoop with the stick, throw it ahead underhanded, and race ahead to scoop again while your team cheers you on.

But for many students, the favorite part of their Crow Canyon experience is learning to throw an atlatl, the precursor to a hunter’s bow and arrow. It’s a one-handed tool that uses leverage to achieve velocity. “If you have ever thrown a ball for a dog, think of it as a Chuckit,” Hughes tells the students in Ms. Wachtel’s class. “The trick is to hold the atlatl, while the dart goes flying.”

He places a plastic turkey at a reasonable distance from the students, so they have something to aim for. “Follow through with your arm, or the turkey will laugh at you,” Hughes says.

“It’s fun to try to hit an actual target,” says Fifth Grader Vaughn Miller. “They use the atlatl to go to the grocery store!”

The students line up and do their best to hit the turkey, with varying degrees of success. They watch with awe when it takes Hammond only one try to hit her prey. This is a skill that has been with her people for generations, and students respect her expertise.

“It’s definitely harder than it looks,” says Fifth Grader Lane Fender. “It teaches you to respect another culture, even if it’s different from yours.”

“The point of all this is that we need to learn about our American heritage and history,” adds Nico. “We should know where we came from, so we can live better today.”