Colorado Academy’s yearlong Seventh Grade Critical Thinking class is just what its name implies: a learning experience designed to provide students with the tools and time to reflect on themselves, their communities, and the world. As the only Middle School course that is offered pass-fail, Critical Thinking encourages Seventh Graders to venture “outside the box,” taking risks and questioning their own ideas—and those of their peers—as they work through a series of challenges carefully constructed to hone key disciplines and skills, such as close reading, creativity, persuasive writing, public speaking, digital literacy, and multimedia design.

“Critical Thinking is the ideal vehicle for teaching in depth the things that we believe are essential for children’s success now and in the future,” states Middle School Principal Bill Wolf-Tinsman, who worked with faculty members and administrators to introduce the one-of-a-kind social studies course 12 years ago. “And Middle School is the perfect time for those things to mature and take root.”

Based on CA’s “Six Cs”—the 21st century skills that are woven throughout the curriculum in every grade: communication, creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, character, and cultural competence—the challenges in Critical Thinking emphasize the themes of identity, diversity, justice, and action. But each year, the specifics evolve to keep pace with the ever-changing social and political realities students encounter through their relationships with peers, discussion with family members, experiences on social media, exposure to news and opinion sources, and more.

“This course feels incredibly relevant,” says Middle School social studies teacher Forbes Cone. “Fundamentally, it acknowledges that our students are surrounded by a huge amount of information and opinions, and it works to give them the capacity to make decisions for themselves. We’re helping students understand that they’re a product of their environment, and they’re susceptible to all sorts of messages around race, gender, socioeconomic status, and the like. By making that explicit, Critical Thinking enables them to interpret that landscape and make choices with their eyes wide open.”

Seventh Grader Rahul Iyengar attests, “It revolutionizes the way you think about something. I used to run into things head first, in a bit of a ‘shoot, fire, aim’ process. In this course you end up thinking about new problems, challenges, and information that you receive in a completely different way.”

From the personal to the political

Critical Thinking begins with a focus on identity. Students delve into the components of their own sense of self, investigating family history, inventorying their values, confronting stereotypes, and composing an “identity poem.” They explore these ideas as they contrast the book Swimmy, by Leo Lionni—about a clever fish who shows his friends how to work together—with the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French political theorist who wrote about a social contract that balanced individual liberty with the common good.

According to Middle School social studies and English teacher Elisa Stolar, “This part of the class is always fascinating. Seventh Graders are really starting to become conscious of how they are individuals, and how they are also part of a group. I tell them some of my stories, and I remind them that they have their own. I think it’s empowering for them to have an adult figure in their lives who says, ‘Your story matters.’”

From there, the course moves on to looking at the notion of diversity, with a heavy emphasis on political discourse, ideological conflict, news literacy, and ways of distinguishing between facts, opinions, and biases. As Cone explains, “We’ve seen our politics become so much more contested and opinion-based in the last decade or so, and it’s increasingly important that our students have mechanisms for coming to their own conclusions about major issues. Becoming more civically engaged and aware is a valuable life skill that will pay off, no matter where they go or what profession they pursue.”

Students culminate this unit by creating a video analysis of the viral “Clock Boy” incident, when a Muslim ninth grader, Ahmed Mohamed, was wrongly arrested at his Texas school for bringing in an electronics project that teachers believed was a hoax bomb. Critics of the school and police responses labeled this an example of Islamophobia, and many prominent figures, including then-President Barack Obama, defended Mohamed. Students in Critical Thinking survey the coverage of the controversy and use their findings to reflect on media bias.

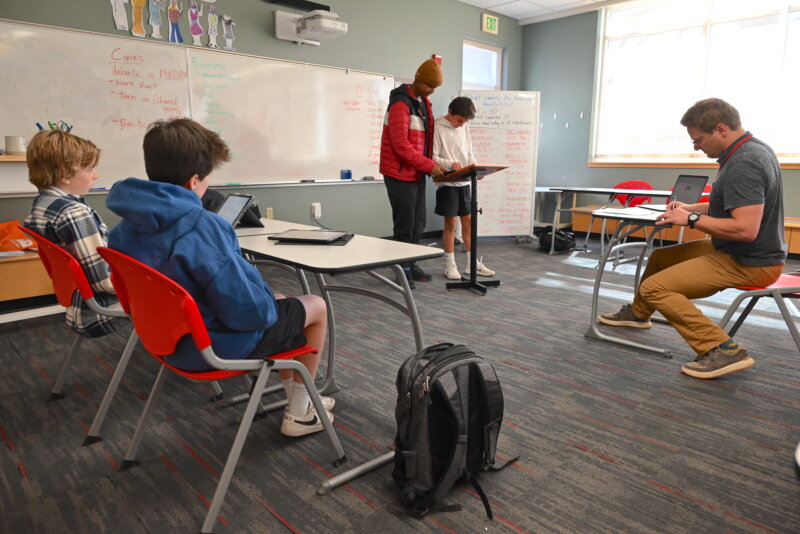

Armed with both a new self-awareness and a deepened ability to evaluate information sources, Seventh Graders next tackle the debate challenge, regarded by many past participants as one of the highlights of their Middle School experience.

Together, students choose a debate topic that they will consider over the course of eight weeks during the winter trimester. Their choice inevitably touches on issues that feel urgent and relevant to Middle Schoolers, ranging from the idea of paying college athletes to the potential threats of artificial intelligence and the merits of tuition-free college.

“When we designed Critical Thinking,” explains Wolf-Tinsman, “we were well aware that students learn more, and more deeply, when they study things that interest them. The debate is a great example of using an important current issue to give students a real sense of ownership and engage them on multiple levels. Like all the course challenges, the debate is really a vehicle for asking some central questions: What skills do I need to be creative? How can I be a better communicator? Can I support my ideas with facts and evidence?”

The Seventh Graders must research the pros and cons of the chosen topic and then prepare arguments, evidence, and rebuttals on both sides; during the series of debates that follows, they’re randomly assigned to one side or the other with the flip of a coin. According to Seventh Grader Mady Iten, the element of randomness raises the stakes considerably. “It’s incredibly important to have your evidence and everything written out,” she says, “as well as to practice being calm and composed. It can be a little bit scary going up against a classmate, but it’s important to focus on what you’re trying to achieve. The debate has really helped me to focus on what somebody else might be thinking—being able to understand that is very valuable.”

After teams of two debaters have competed against multiple opponents in round robin-like classroom sessions, the unit concludes with a final debate, during which the classroom champions face off in front of the entire Middle School; a panel of past debate winners judges their performances. “What I love about the debate,” says Cone, “is that students may come in having an opinion on the topic, but then through their own research, through watching other teams debate, I find that their thinking often becomes more nuanced.”

Still, Cone explains, once the debate is over, the class quickly moves beyond the idea of winning and losing. “The debate unit is really about listening and seeing things from multiple perspectives, not about determining winners and losers. We’re trying to get to an understanding of deliberation, where people come to the table with different points of view, and we can collaborate to come up with a solution that benefits everybody.”

The concept of deliberation is central in the final phase of Critical Thinking, when students participate in a simulated court trial presented by the Colorado Lawyers Committee’s Hate Crimes Education program. Students study a fictional case arising from a violation of Colorado’s Hate/Bias-Motivated Crimes Statute, and at the conclusion of a trial staged by real lawyers and judges, small groups act as jurors to discuss the issues presented and, with the assistance of an adult facilitator, reach a verdict.

This is the part of the course where justice and action take center stage, and, says Cone, it’s where the abilities that students have sharpened during the preceding weeks and months meet the realities of our world.

“Now that we understand that we all exist within systems in our society, and that some groups of people have benefited from these systems and some haven’t, we have to ask, what are the consequences? What do we do with our knowledge? Now that we can consider different perspectives, how can we go out into the world and be more intentional and engaged?”

Looking at the issues around hate speech—the debate between what counts as free speech, a concept enshrined in the Constitution, and what crosses the line into speech that actively causes harm—encourages students to grapple with all these questions, and more. “They have to decide whether speech—though it may be protected by our laws—can either be beneficial or destructive to society as a whole,” Cone says.

A time to reflect

At the very end of Critical Thinking, students look back at the challenges they’ve encountered, and they build a visual “monument to learning” that encapsulates all the ways that they have changed and grown during the course. But students are not the only ones who take the time to reflect.

For Wolf-Tinsman, one of the most compelling aspects of Critical Thinking is the way it changes every year. Throughout its long existence, he says, CA’s supremely creative faculty members have evolved Critical Thinking to make it more relevant and impactful than ever—continually reshaping the classroom “weather” that nourishes learning. From including an investigation of foreign actors conspiring to influence the results of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, to surveying Middle Schoolers about what most impacts their success in school, teachers have ensured that the course remains at the heart of the Middle School curriculum.

Yet, Wolf-Tinsman says, Critical Thinking is no outlier at CA. On the contrary, the ideals that continue to drive the course are the same ones that can be seen in any Middle School classroom.

“When visitors ask me how we are teaching creativity, problem-solving, and all the other 21st century skills, I point them to our ThinkingLAB,” says Wolf Tinsman. A complete curriculum map that details the ways that the Six Cs come to life in every subject area, from language arts to math, ThinkingLAB represents CA’s stake in the ground on the teaching of skills critical for the future.

“If we’re consistently working to make sure our students can be successful learners, creators, and collaborators, then we’re pretty sure they’ll be ready to take on the five to seven jobs, on average, that they’ll go on to do in their lives. The days of being able to stick with one thing your whole career are over. Flexibility and the fundamentals of understanding and communicating are the goal.”

According to Cone, Critical Thinking plants seeds that will grow throughout students’ academic lives and beyond.

“By asking them to reflect through their monument to learning, and by tying the earliest lessons in the course about identity to the larger themes of justice and action, we’re helping students make profound connections that can’t be undone,” he says.

Cone recalls one student whose grandmother was old enough to have met Benito Mussolini as a young girl. Considering her stories about the encounter with the fascist dictator of Italy prompted students to look more deeply into the historical context of that moment, when Mussolini’s Italy was pursuing colonial power throughout the region and aligning itself with Germany and Japan before the outbreak of World War II. Another student’s father had emigrated from Somalia to escape civil war; still another’s family had escaped famine in Ethiopia.

If you were to hand these students research projects about these events in history, Cone argues, they’d be “bored to tears.” But anchoring learning in their own stories creates powerful buy-in and inspires new insights that couldn’t come any other way.

“I think that’s why I love teaching this course,” says Cone. “I’m so much more comfortable in the role of guiding and supporting, rather than lecturing at students. I love learning from them.”