The term “fake news” has entered the vernacular in recent years, but there is nothing phony about the study done by distinguished researchers at Stanford and New York University titled “Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media.” Those researchers recently published their findings after studying 570 fake news websites and 10,240 fake news stories on Facebook and Twitter over a three-year period. Not too far behind them in the study of fake news are Colorado Academy’s Seventh Grade students studying digital literacy in their “Outside the Box: Critical and Creative Thinking” course.

Digital literacy

Outside the Box is a yearlong social studies course designed to help students examine contemporary social issues from a variety of perspectives. Digital literacy is just one of many topics students tackle. “Our students are inundated with an enormous amount of information,” says Middle School social studies teacher Forbes Cone. “We have an obligation to give them the tools to make sense of that information.”

Teachers introduce the concept of digital literacy by asking students to consider key questions: What is news? What makes news newsworthy? What is bias? What is the role of news as democracy’s watchdog? How can you recognize a fake news story?

“There was a time when you would read something and have reasonable confidence in the editorial process,” Cone says. “There was possible bias, but at least the content was not made up. Now anything can be published and look authoritative, so how can students filter between reliable and fake information?”

Since their online experience is curated based on their search terms, students study the role of algorithms in their searches, learning how an algorithm might limit their ability to see different perspectives, creating an echo chamber of information. They study real-world examples of fake news like the infamous “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory that linked members of the Democratic Party to alleged child trafficking in a Washington, D.C., restaurant and led to a shooting incident.

Then students took what they had learned and researched the world of fake news on a new level.

Fake tweets and First Amendment test

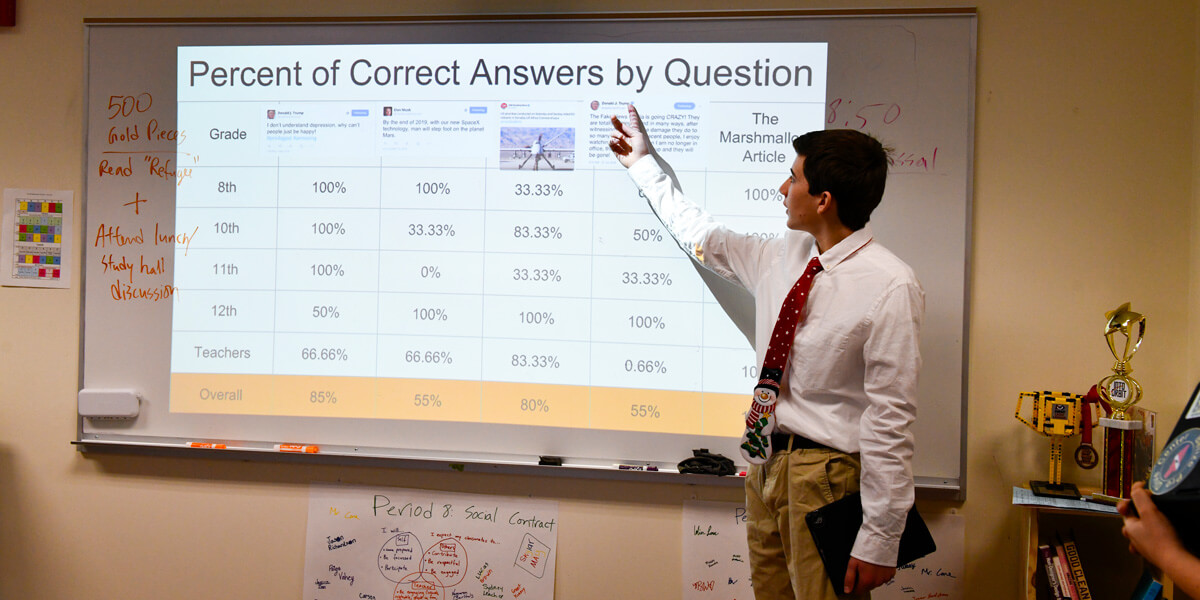

Working in small groups, some students created surveys with examples of fake and real tweets and asked respondents—including younger students, older students, faculty, and staff—to distinguish the real from the fake. They had to design the survey, figure out how to deliver it, collect and analyze their data, and present their findings to their class.

Fraser Smith’s group titled their survey “Ridiculous or Real?” One example in the survey appeared to be a tweet from Carolina Panther Quarterback Cam Newton: “Participation trophies are a joke and encourage kids to be lazy.” Another appeared to be from Los Angeles Chargers QB Geno Smith: “I been studying this whole flat earth vs. globe thing…and I may be with Kyrie on this…b4 you judge do some HW but what do you guys think?” So which of those tweets is real, and which is fake? Keep reading to find out.

For the students, having to create fake tweets created a whole new understanding of how easy it is to fool people. “Students have to switch positions from being the student to the teacher,” Cone says. “That requires a much deeper understanding.”

Fraser confirms his teacher’s observation. “It made me more aware of fake news, verifying sources, knowing that what I am reading may not be true, and it helped me look at news in general.”

Another group of students did a survey researching how well students in different grades, as well as faculty and staff, understand their rights under the First Amendment. Basing their questions on research of Supreme Court decisions, they asked respondents to decide whether the First Amendment protected students’ right to peacefully protest at school, their right to buy violent video games without parental consent, and the right of a news organization to publish false information that damages someone’s reputation if it is done unintentionally. How would you have done on that survey? Again, keep reading if you are curious.

“You should know which of your rights are protected because it’s part of what makes our country free,” says Nora Knight, one of the participants in the First Amendment survey. “People may not understand how it impacts them, but it’s an important part of our democracy.”

What students learned

The Seventh Grade collected data from their surveys and analyzed it by grade, gender, role at the school (student, faculty, staff) and learned, in general, that students who had already taken CA’s course in digital literacy were best equipped with the tools to spot fake news.

How well would you have done? In the case of the First Amendment survey, all three of the examples are protected. In the case of the tweets, only the tweet from Geno Smith is real.

The students’ study of digital literacy culminated in a final debate with the affirmative and negative team arguing the merits of this resolution: “Social media strengthens democracy.” Students were evaluated on how well they stated their position, the clarity of their logic, the strength of their evidence, their public speaking skills, and their ability to handle cross-examination, among many criteria. The two winners were Ellen Clowes and Sydney Leach.

And the distinguished researchers in whose footsteps CA students are following? Their research led to this conclusion, among others:

“User interactions with false content rose steadily on both Facebook and Twitter through the end of 2016. Since then, however, interactions with false content have fallen sharply on Facebook while continuing to rise on Twitter….”

It’s a conclusion that reinforces CA’s commitment to develop students’ evidence-based reasoning skills—especially in the midst of an environment in which falsehoods can masquerade as truth.