In November 2022, Collinus Newsome arrived at Colorado Academy to lead the school’s Office of Inclusivity. A nationally known strategist, facilitator, and educator who has served as a co-chair for the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) People of Color Conference and is a longtime co-chair of the NAIS Student Diversity Leadership Conference, Newsome was a natural pick to step in as Interim Director of Inclusivity. The role is closely aligned with the school’s public 2020 commitment, laid out in a letter signed by Head of School Dr. Mike Davis and the Board of Trustees, to advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) at CA. That statement’s broad vision called for systemic changes in the areas of recruitment, curriculum, and programming, among other priorities, and it created the Office of Inclusivity to spearhead these initiatives.

Today, Newsome’s title is Director of Culture and Community—an update that speaks volumes. The shift reflects not merely the evolution of the critical position that Newsome will occupy as CA strives to answer the nationwide call for all institutions to address systemic issues of racism, discrimination, and inequality, but also, and most importantly, the much wider scope of the work that, according to Newsome, the CA community must undertake together if it is to meet that goal.

“Inclusivity is not a one-person job—it takes all of us,” says Newsome. “In the past, the person in my role has been seen as the one individual you call when an issue crops up—a sort of consultant to manage crises and solve problems.” This is true not just at CA, she explains, but at independent schools all across the country.

Newsome acknowledges the important contributions of past Directors of Inclusivity, including CA’s first, Adrian Green ’05, who took on the role in 2014, as well as his successors, including Sarah Wright. She points out that the school’s efforts toward building an inclusive community stretch back even further, to the work undertaken by dedicated faculty and staff such as Darnell Slaughter Castleman, Paul Kim, and Carolyn Cunningham Ash ’87.

This long history has resulted in undeniable progress: the CA community is more diverse than ever, with 32% of students self-identifying as people of color. Extensive services, programs, and events—not to mention a forward-looking, justice-inspired curriculum that spans Pre-K to Grade 12—foster ongoing learning, support, and growth across all constituencies at the school.

Still, relying on the efforts of a few individuals to effect large-scale, systemic change is not how a school truly moves the needle on issues of equity and belonging, Newsome insists. “In order to do this work well, you actually have to shift the culture. You can’t start to change systems deeply until you create a culture of humility.” She challenges, “What if we stop making the performative or business case for DEI work and instead make the human case—how would that change the nature of what we aspire to do? In order to do that, we must first ask ourselves, ‘How do we want to be for and with each other?’”

A changing community

The significance of that question for CA came as a revelation to Newsome, who spent her first months on campus observing and absorbing the culture and climate of the school. Visiting classrooms, meeting with students and teachers, and talking with administrators, Newsome says she encountered welcoming and engaged individuals at every turn.

“I saw that CA students know they can show up as themselves; a sense of excitement and enthusiasm about that—and even playfulness—pervades the campus.”

During one classroom visit, Newsome recounts, a Fifth Grader eagerly told her about her project on the Underground Railroad. “She saw that my eyes lit up about that topic, and we were able to have a wonderful conversation about what she was learning. When I asked her questions, she was honest about the things that she was struggling with or that she wanted to know more about. She was just herself, and it was so fun for me.”

But as she learned more about CA as a whole, Newsome found herself wondering how those individual moments of growth and connection—whether in a Fifth Grade classroom, a lunch table conversation, or an advisor’s support for a student—contribute to a shared culture.

“We do so much as a school,” says Newsome. “We have incredible programs such as Horizons Colorado and REDI Lab, we host renowned speakers, we support robust after-school and summer offerings. But what is our North Star? How do all these things and all this activity work together to get us closer to being the inclusive community that we aspire to be?”

At the same time, independent schools such as CA have felt an increasing sense of urgency around issues such as racism, privilege, and identity. The 2020 murder of George Floyd brought a flurry of commitments, many of which, like CA’s, led to action. The isolation and accompanying self-reflection of the COVID-19 pandemic added momentum, as white Americans increasingly seemed to understand what communities of color had been telling them all along. But in the rush to act, Newsome says, it was easy for schools to skip the critical first step of identifying how, precisely, they would enact real and lasting change within their communities.

All this, according to Newsome, means “It’s time for CA to step back.”

“We need to focus on rebuilding relationships with one another, on tending to the culture and climate of the school,” she says. “Let’s elevate those bright spots, where we really show up for one another, where people really feel like they’re seen and heard.”

Newsome cites a recent experience sitting down with a group of Lower Schoolers for lunch. “When I just walked up to their table and joined them, they didn’t treat me like a stranger. We got involved in a conversation right away. They were curious and had no fear when I asked them questions. When I popped into their classroom later, those same students all waved hello.”

But Newsome also points to patterns that are concerning. Particularly at the Middle and Upper School levels, she observes, “The stakes in the classroom feel higher. Students seem to lose some of that curiosity and openness to exploring the world around them.” And as a result, she says, both students and teachers put up guardrails, unstated parameters that limit how they show up and the conversations they have about difficult topics such as race.

And, while Newsome, in the months she spent learning about nearly every aspect of the school, met many individuals who are passionate about equity and inclusion and are deeply engaged in these ideas, she also noticed signs that some community members may not be fully aware of divisions that persist.

“We’re not yet asking the right questions of ourselves. Are all the boys sitting on one side of the room, and all the girls sitting on the other? What does that observation tell us? Just like we celebrate the bright spots, let’s also call out those moments where we are not yet who we want to be,” Newsome says.

“The real work for CA,” she continues, “is reimagining who we are in relation to one another, honoring each individual’s lived experiences and stories without judgment. There is a sacredness in that.”

A father’s story

Newsome arrived at her understanding of the human relationships at the center of any inclusivity work through decades of experience, both personal and professional.

As one of eight children growing up poor in rural Mississippi, Newsome saw firsthand the legacy of racism in America. Slavery had occupied a central place in her home state’s economy and culture before the Civil War, and its impacts continued to reverberate all the way through the civil rights movement and beyond.

“Many people don’t understand that even then, in the 1950s and 1960s, the rural South was still a dangerous place for Black men,” she says.

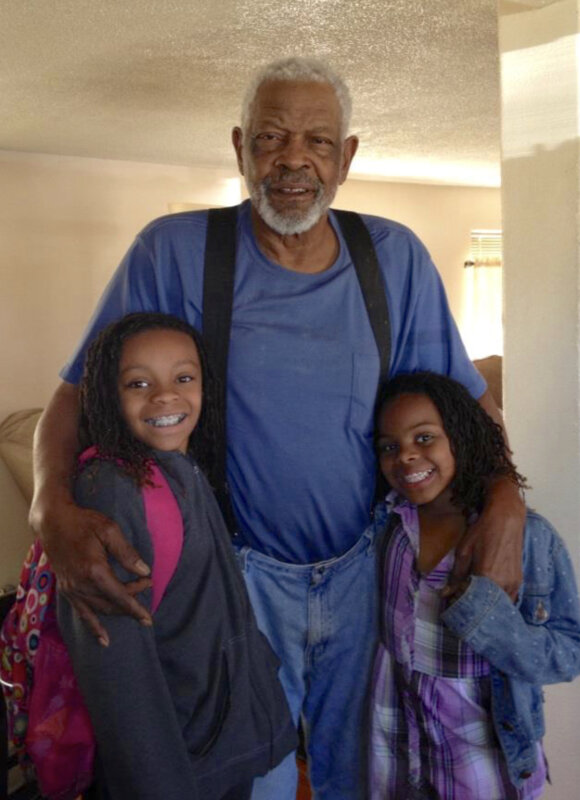

Life in Jim Crow Mississippi was “brutal” for her father, John, according to Newsome; he never went to school or learned to read or write because he, just like his seven brothers, had to work as a sharecropper to support the family. But a turning point came in 1955, when Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy, was lynched after being accused of offending a white woman in her family’s grocery store. The same age as Till, “My father understood then that he would one day take his family somewhere else,” Newsome says.

That aspiration eventually led them to Denver, where they rented a two-bedroom apartment in the historically Black Five Points neighborhood. Part of the last wave of the Great Migration, which took approximately six million Black people from the South to northern states between the 1910s until the 1970s, Newsome’s family found reason to celebrate their journey.

“In the Five Points in the early 1980s, we were all poor,” recounts Newsome. “But we didn’t know we were poor—we had all arrived from various Southern states. We were a community, and we saw opportunity.”

Newsome’s father took a job as a janitor at the Gates Rubber Company, whose headquarters were located a stone’s throw from Five Points, and with the help of colleagues who taught him to read and write, he was able to earn his GED and then attend community college to study engineering. He went on to graduate from the Colorado School of Mines as a chemical engineer and had a successful career that took him all the way to South America. The family settled for good in Northeast Park Hill, another historically Black enclave like Five Points, but one that, with its tree-lined streets and attractive homes, symbolized accomplishment and even affluence.

Newsome centers her father’s story in the narrative of her own life, she acknowledges, because it so clearly reflects the obstacle-strewn path—mapped by racism—so many Black Americans must follow as they seek to survive and succeed.

“My father’s sacrifices changed the trajectory of our lives,” she states. “The life he built for us ended generational poverty in our family, and enabled me and every one of my siblings to become first-generation college graduates and to find their own career success.”

That powerful family arc—the meaning it communicates to anyone who wonders where she came from and what shaped her—speaks to one of the pillars in Newsome’s approach to building inclusive communities.

“Holding the stories and lived experiences of people who might be different from you with humility and without judgment places the emphasis on the relationships and trust that are at the heart of any systemic work,” she explains. “When we really lean into that, we’re fundamentally changing minds and behavior.”

Challenging spaces

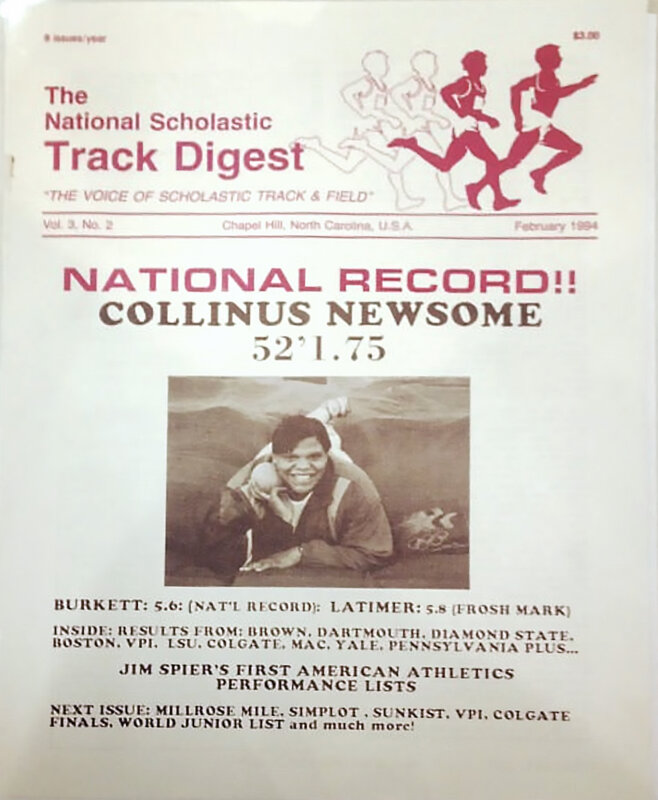

The upward trajectory Newsome’s father had set for her and her seven siblings took her far.

As a teenager, she joined the legendary Colorado Flyers Track Club and trained at the same recreation center that launched Chauncey Billups, the former NBA star and now coach of the Portland Trail Blazers, who is just one of numerous exceptional athletes who trace their start back to Northeast Park Hill. Newsome became one of the nation’s top high school shot putters and earned a scholarship to attend the University of Illinois, Urbana, where she was named the National Big 10 Freshman Athlete of the Year and went on to win seven Big 10 Championships in the shot put and earn six All-American titles. After graduation, she obtained a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction at CU Boulder, and taught at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in far northeast Denver.

In her next position, as a ninth grade history teacher at Graland Country Day School, where she was also responsible for the school’s diversity work, Newsome began to see the broad scope and deep significance of the community building that would define her career. She became a better teacher and facilitator, arriving at a profound understanding of the nature of DEI work in primarily white institutions, including CA, which has long been connected to Graland and where Newsome encountered some of the school’s early inclusivity advocates.

She moved on to inner city public education, where the differences between those schools and institutions such as Graland stood out in even starker relief, and then to the Denver Foundation, where she worked toward equity throughout the metro area. Newsome eventually took a senior position with the Colorado Health Foundation, which focuses on health equity, often in rural areas, by investing and advocating on behalf of people who have less power, privilege, and income, and prioritizing Coloradans of color.

It was there, according to Newsome, that she discovered the “secret sauce” that is the cornerstone of her approach today.

“Working toward health equity in rural Colorado,” she says, “I immediately found myself the only person of color in rooms full of white men in cowboy hats—ranchers. My job was to help them understand the experiences and needs of those in their communities who were most vulnerable—often, Latine families. But even though the Colorado Health Foundation’s mission prioritizes people of color in all its health equity work, I knew I couldn’t go into those rooms and start with the issue of race.”

Instead, says Newsome, she started with relationships.

“I realized that the only chance I had to open their eyes to the experiences of others in their community was by first building trust. It wasn’t me saying, ‘You’re racist.’ It wasn’t me talking about white supremacy. Nobody wants that—that just loses people. But when I’m in relationship with you, and I have a shared experience with you—like growing up in a rural area—it makes a difference.”

Spending much of her time getting to know people and connecting with them through her own lived experiences in Mississippi, Newsome was finally able to initiate the difficult conversations that were necessary to create change, and she was inspired by the response she got from those she reached.

“When you can sit in a room full of white ranchers and they ask you, ‘What do you think we should do for our immigrant community? How can we help them?’—that is what trust looks like,” she says.

“It didn’t mean that we didn’t wrestle with issues around racism and access to housing and health care, for example,” continues Newsome. “All of that was on the table. I just had to approach it from a place of empathy and kindness and compassion. That’s how people can see the real, systemic issues.”

“Do no harm” became her mantra as she challenged rural communities to appreciate the vulnerabilities of others and to hold themselves accountable for taking much-needed action. The approach paid off in impact and connections that endure.

“There are people I met who still call me and ask me for my advice. They ask about my family; they offer to give me half a cow. When you are willing to be in relationship with someone, that is how we can do this work together. Through human connection, you can accomplish really tough things.”

The work ahead for CA

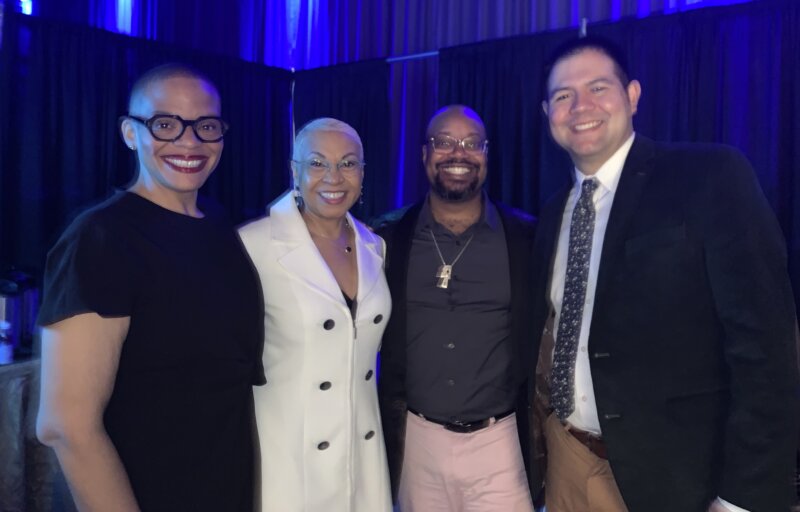

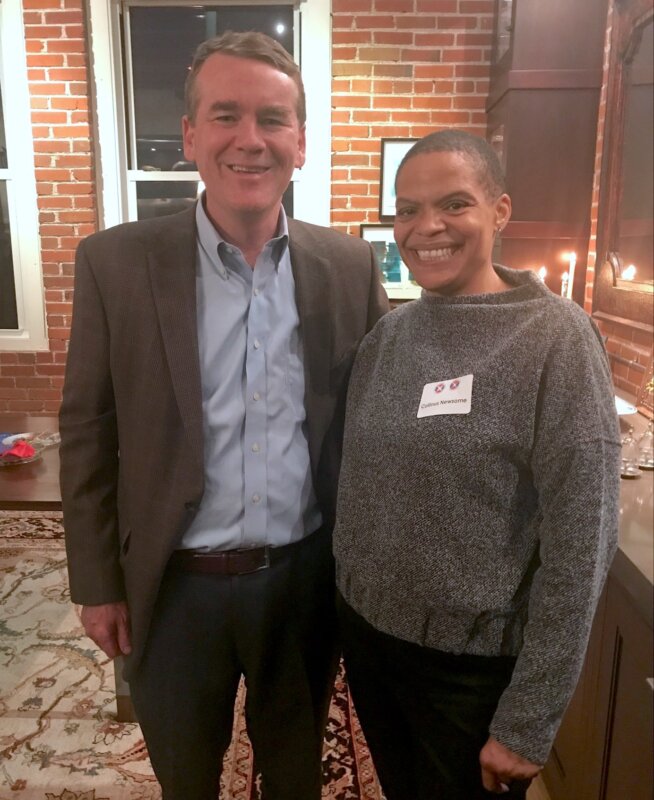

Reflecting on the path that brought her to CA, Newsome observes, “It’s kind of funny how it came to be. I got a call from the Director of Diversity at Graland, my friend and SDLC co-chair Oscar Gonzalez, and the next thing I know, I am talking to Mike Davis, and, well, here I am.”

She continued those conversations with Davis, and in finally settling on her title—and mission—at CA, the two returned often to the notion of empathy.

There is no doubt, she says now, that in her new role, all that she’s learned about using empathy to build relationships in places like Cheyenne Wells, Colorado—and all that she knows about successful communities from her own experiences in Five Points and Northeast Park Hill—comes into play.

She keeps a sticky-note on her computer so that those lessons stay top of mind: “Show empathy. Show kindness. Show humility. Give people dignity and respect. Hold their stories and lived experiences with the sacredness that they deserve.”

Those words guide her as Newsome begins to ask the CA community—students, teachers, and families—to “build muscle” around some of the practical skills that will allow it to repair the relationships at its heart. That practice, she says, begins with noticing what causes harm to those connections and then calling it out—not to blame or shame, but to inspire the vital conversations that strengthen community ties.

“We just assume people know how to have difficult conversations,” she says. “But they don’t. That’s a skill we all need to work on.”

Classroom practice is another area where Newsome is optimistic CA can make strides. Nothing new to CA faculty members, culturally responsive teaching is a framework that asks teachers to build a respectful, relevant learning environment through actions such as pronouncing students’ names correctly and inviting them to bring their own experiences, prior knowledge, and culture to the table.

“Culturally responsive teaching is not ‘in addition to’ everything else that happens in the classroom. It’s just good teaching. Every student benefits from this practice when we are intentional and rigorous about how we plan for the learning experience of each student who shares our classroom space. We already know that in many ways; let’s build our capacity to be better. Everything we do should be done with excellence at the center.”

Just as with entering into difficult conversations, the ultimate goal of culturally responsive teaching is ensuring that every student can see themselves reflected in the learning environment. Cultivating a sense of belonging starts in the classroom.

“There is a subtle but significant difference,” Newsome observes, “between a student who feels invited into a community as a guest, and one who feels an inherent sense of belonging and shared ownership within their school environment.”

Room for all

Belonging may be the goal, but what does that mean for CA? Newsome has a metaphor drawn from her own experiences that suggests an answer.

“My good friend, Dr. Rodney Glasgow, Head of School at the Sandy Spring Friends School, and I have talked about what belonging feels like: when you feel welcome, you feel like you could come in, and you’ll be okay, and you could, to a degree, make yourself ‘at home.’ But when you belong, you already are at home. You know where the milk is kept in the refrigerator. You know where your favorite slippers are. You might even have a key, though it might not be your own home.”

Or, Newsome continues, she thinks about her children inviting their friends over to visit. “They know that when they walk in, they take their shoes off, and they can go right to the kitchen to find the snacks. They feel comfortable just sitting down to talk. In our house, we’ve established a space where they feel cared for—it belongs to them, in a sense.”

Still, it can be easy to get caught up in the idea of belonging as everybody having the same experience, Newsome explains. “That’s one of our blind spots as a school: because so many of our families, students, and faculty have a similar profile, we just assume people feel they belong. But that can actually be harmful.” Conflicts arise when some members of a community as large as CA fail to understand that CA might be something different for others.

Belonging, she continues, means that no one has to have the same experience, and that there is space for all. “Yes, we are CA,” she acknowledges. “But what is the heart and soul of CA? Is it the sports, the academics? Every person who steps on this campus should have the ability to shape the experiences that are most meaningful for them, and every individual should find room to do that.”

When she speaks about belonging at CA, Newsome often references Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s notion of the “Beloved Community.” The philosopher-theologian Josiah Royce, who helped to found the interfaith Fellowship of Reconciliation in the early 20th century, coined the term to describe a heavenly utopia on Earth. King, a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, popularized the term and invested it with a deeper meaning.

King’s Beloved Community envisions a critical mass of people around the world committed to and trained in the philosophy and methods of nonviolence. Poverty, hunger, and homelessness are not tolerated. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry, and prejudice are replaced by an all-inclusive spirit. Inevitable disputes are resolved through peaceful conflict resolution and reconciliation. Love and trust triumph over fear and hatred.

According to Newsome, CA’s beloved community most likely won’t look exactly like King’s vision. “It has to be our beloved community. There’s no roadmap; there’s no script.”

That leaves the community itself to decide on its own definition of “beloved” by agreeing, collectively, on who we are and what we value. “In order to do that, we will need to come together and co-create that beloved community,” Newsome says. “And when we do, every single one of us owns it.”

A planned survey about school culture and climate—intended to capture data about how people experience CA’s admissions, curriculum, hiring practices, and every other facet of what makes the school run—will inform that decision-making process.

Then, says Newsome, it will be time to ask ourselves, “How do we want to be for and with each other? How will we shape the school community we really want to be?”

Posing such questions makes her work all the more difficult, but challenging communities to heal themselves is inherently hard work. It is work that Newsome has found herself involved in again and again throughout her career.

“I can’t seem to get away from it,” she says.

Evoking King again, she talks about the leader’s “at-the-kitchen-table moment.” Fearing for his family and facing death threats while the Montgomery bus boycott was roiling the American South, King felt he heard a voice from God telling him how to persevere despite exhaustion and hopelessness.

The voice said, “Stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And know that I will be with you, even until the end of the world.”

Growing up in the rural South, where King’s voice held so much weight, is part of the reason these words resonate for her, Newsome says.

“As a woman of faith, just like for Dr. King, this work feels like a calling for me. And when I lean into that, doors seem to open, no matter where I am. But I also love this work, because I truly believe in people. I believe in humanity. I have to, in order to sustain myself in this work, which comes at a cost for me and for so many others. If we don’t carry this burden together, it will be impossible for us to do the hard work that’s coming. We must carry the burden together.”