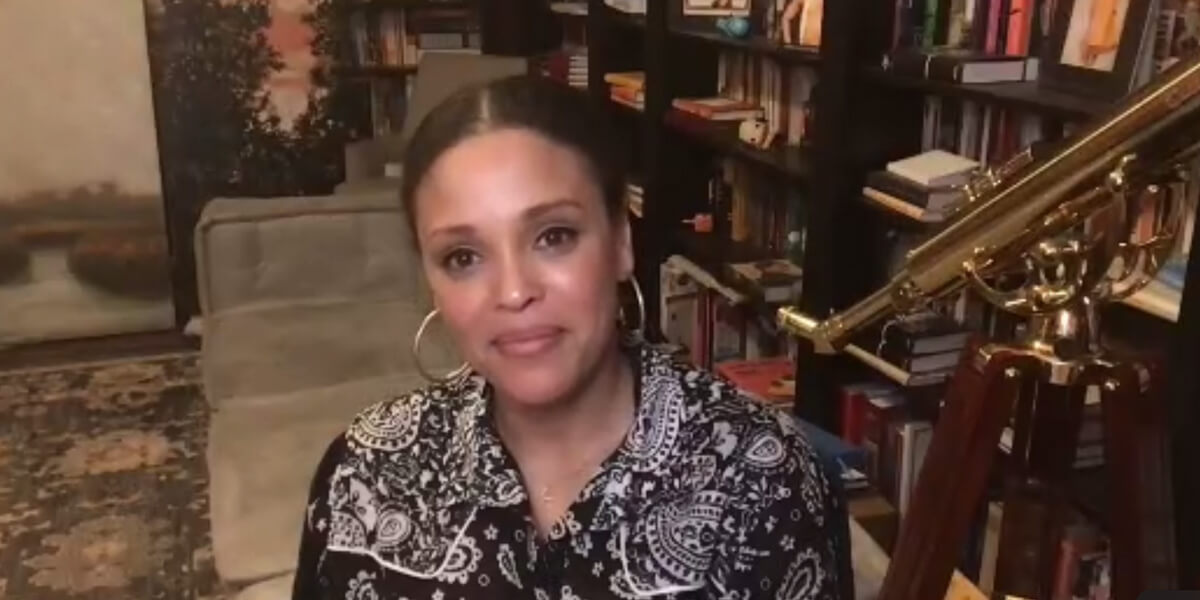

MacArthur Genius and two-time National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward is the author of fiction, nonfiction, and memoir that the New York Times Book Review called “raw, beautiful and dangerous.” In 2017, she became the first woman and first person of color to win the National Book Award for Fiction twice, joining the ranks of William Faulkner, Saul Bellow, and John Updike. She spoke at the Colorado Academy SPEAK series in a conversation with CA Director of Inclusivity Sarah Wright.

How do you balance writing for your community—the rural South—and for people who are not part of your community?

“Some readers may have difficulty approaching my work, because they make assumptions about the kind of characters I write about. If the readers are not poor, Black, and from the American South, they question whether these characters are relevant to their experience. I hope that when they read my work, they still see these characters as visibly rendered and fully embodied, so that the particulars of the characters’ experience seem human and real to the reader.

“When that happens, the reader will experience them as real people and feel a sense of intimacy, so that the kind of people I write about transcend their circumstances. The reader will experience them as people, dealing with heartbreak, loss, living with joy, and all of the complicated aspects of our humanity.”

As a child, I wasn’t really a lover of reading. I don’t know exactly why that was. Perhaps, I just had not found my genre?

“I was aware that I loved reading from the time I was very young. I read everything I could get my hands on. But it was hard for me to find the kind of people I grew up with and to see some aspect of my life reflected in literature. Still, I loved reading, because it allowed me to escape into a world that was nothing like mine. And that is an important function of reading.

“The other function of reading is that you need to see yourself in the stories you read. I did not. I think that motivated me to write the kind of stories I write now. I was writing about the place I come from, born out of this need to see myself, to feel I had a voice, to feel that the people around me had a voice. I read plenty of Southern authors when I was growing up, and I saw bits and pieces of my world, but I still felt invisible. And I still felt the people I knew and loved were invisible too.”

Who were some of the writers who influenced you?

“I remember reading Richard Wright’s autobiography about growing up in the delta, and how he would go outside and put his mouth to a water spigot and drink until his stomach was filled, so he would feel less hungry. That resonated with me. It says something about the poverty of my background. Alice Walker—I was really impressed by how she wrote in first person. I remember reading Toni Morrison and being struck by the quality and beauty of the poetic language. It took me a long time to appreciate Faulkner. I didn’t understand the love for him until I was 26 and read As I lay Dying. And then it was like being struck by lightning.”

What is it about As I lay Dying that was such a powerful influence on you?

“The voices of the people are so alive and distinct. The way they use language, how they process the world, how they speak and tell their stories, it was so beautiful, and it had so much texture and so many layers. I had to read it multiple times. It functions like poetry for me. For me, poetry teaches lessons about what language is capable of. It’s compressed, and sharp, and inventive, and creative, and it can make you see the world in a totally different way. A lot of poets I loved growing up include Natasha Trethewey and Pablo Neruda.”

Historically, Black women are often silent. How do you empower and give voice to women in your books?

“There are stories told about us, but we don’t often get to tell our own stories. Only certain Black women get to tell their stories. Even those who do get to tell their stories, they feel reduced, their narratives are flattened, they are not allowed to be nuanced and complicated, they have to be one thing or another. I want the opposite of that for Black women I write about. I love to write from the first person. Then I am not a part of the equation, and these women can speak through me. When I write a book, it feels like I am transcribing what they are telling me.

“In the first-person narrative, Black women tell their story and get momentum. I feel like they are allowed to be complicated. In Sing, Unburied, Sing, there is a mother—an abusive mother—and she is able to tell her story. We understand why she may be using drugs, the trauma she has endured, and how that plays a part in her behavior toward others. We can see her as a fully rendered human being, so we feel sympathy. I hope the reader carries that sympathy out of the book, so when we encounter a person like her, we feel empathy for them.”

In Navigate Your Stars, you talk about how you didn’t see yourself as a writer and how hard you had to work to become a writer. It was not easy!

“I was a reader first. I loved stories and storytelling and books. It seemed that authors could accomplish magic, but when I was young, I did not think I was capable of making that magic. As I grew up, I was the first person in my extended family to attend college—I went to Stanford. There was pressure from my community to do something practical and smart like go to medical school or law school and earn a steady paycheck. So being a writer was not on the table. I grew up in small rural town in Mississippi. My family has lived there—in poverty—for generations. I was very aware of the difference in quality of education in rural Mississippi versus what I saw at Stanford.

“Recently, I learned the term “imposter syndrome.” Every class at Stanford, I felt like an imposter. I thought I didn’t deserve to be there. I was so quiet, I hardly spoke! The thing that made me choose writing after I graduated from college what that my 19-year-old brother was hit by a drunk driver and killed when I was 23. It was terribly painful and horribly traumatic. When you lose someone close to you, it changes all your ideas about life. It made me think ‘what will I do with this time I have been given?’ When I asked myself that question, the answer was writing. That was immediately the thing that manifested itself for me.

“That’s when I seriously began to read like a writer. I started writing short stories and worked my way up from there. It took a long time, and I spent many years writing and failing and facing rejection. I almost gave up at one point, but there was always that little voice that said, ‘Try one more time.’ So I didn’t give up.”

What gave you the courage to overcome imposter syndrome?

“After my brother died, I moved to New York City and worked in publishing. I worked with friends on my writing. I did a lot of working my own, reading widely, writing a fair amount regularly, doing the work I could have done as an undergrad, but now in the real world. I went back to school to earn my MFA (at the University of Michigan). There, I was able to begin to share my opinion, share my work with more confidence, be a more effective student, and get the most out of a classroom. In graduate school, the whole first year was about me coming out of my shell, exercising agency in the classroom. By the second year, I was a full participant. I had to do hard work outside the classroom and inside to finally feel confident in my ability to contribute.”

What are you working on right now?

“I’m working on a novel about a woman who is enslaved, sold, and ends up on a sugar cane plantation outside New Orleans. I wanted to write it, because I learned about five years ago that New Orleans was the capital of the domestic slave trade in the United States at one point. There were slave pens all over the city where enslaved people were kept and groomed for sale. I thought I knew New Orleans, but that whole aspect of history of the city, I didn’t know.

“Enslaved people have suffered and endured so much and survived so much. Their stories have been erased from history. As I do the work to educate myself, different things are inspiring me. In this moment, every day, I learn about people, stories, Black Americans whose voices have been erased. I’m becoming more interested bringing those voices back to life.”

You had many rejections before your great success. What keeps you so resilient?

“One of my professors at the University of Michigan said to us, ‘It is easy to stop and give up writing, so you will no longer be rejected. Don’t stop! If you stop, you are taking your own voice out of the conversation, you are rejecting yourself.’

“That was the one of the most important things he could teach us. He was telling us to persevere. Even when things seem hopeless, you shouldn’t give up. A couple of times when I felt like giving up—maybe there wasn’t an audience for my work, maybe I wasn’t good enough to be published—I thought about stopping. But then I didn’t. You have to be stubborn. You have to believe that the impossible will happen. You have to believe in luck. You have to be disciplined. You have to write more often than not. You have to learn how to revise. You have to learn how to take criticism and incorporate that into your work. You have to keep going. There was always something in me that wanted to tell stories, a voice I couldn’t quiet. I couldn’t stop seeing the world like a writer, being curious about people, so inspiration was a factor in my continuing. But it’s funny, there was always a sense of desperation—inspiration and desperation—they go hand in hand.”

During this time of political division, how does literature help us move forward?

“In order to grow and evolve despite trauma, you have to reckon with it, you have to acknowledge it, you have to feel the pain of it. That’s how you survive and thrive in spite of it.

In this country, I’m not sure we reckon with it enough, we don’t acknowledge it, because we don’t embrace our history and hold ourselves accountable and reckon with the fact that the past lives in the present. All the choices that were made in the past have repercussions in the present. As long as we ignore that, we won’t thrive. We have to embrace it, feel the pain, and grow despite it.”