A number of years ago there was a movement to integrate courses into college curricula that taught students how to solve problems—how to imagine, analyze, create something, or satisfy a challenge using the knowledge and/or physical properties available. The logic behind this action was that young people were losing their ability to generate in contexts that did not provide an immediate answer via Google or Wikipedia or to spark a solution from nothing, as rubbing together two sticks to make fire, or envisioning the idiom of castles in the air.

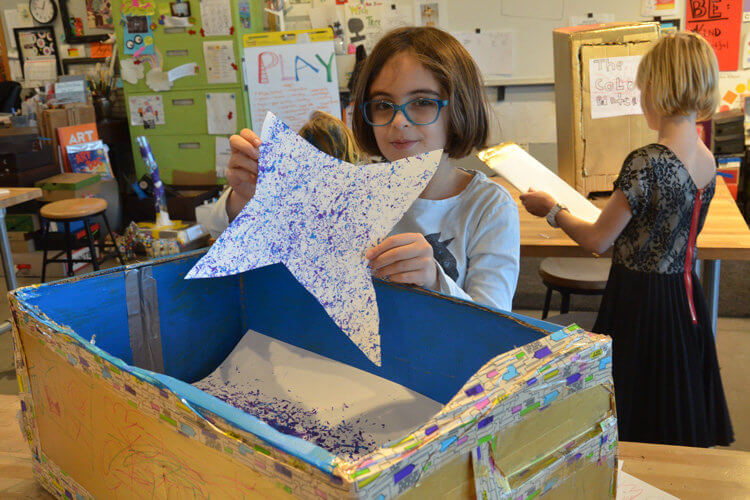

On December 3, the Ponzio Arts Center at Colorado Academy hosted the opening of the Kindergarten through Grade 8 art show—PLAY. As I walked into the building, an enthusiastic band of Lower School students raced across the gallery, bidding me to see their projects. I toyed with “drawing machines” in the form of fabricated robots, a spinning pencil, a chalk-erected wolf claw attached to gloves, and, my favorite, the drawing apparatus on wheels that marked a path as it moved along. I experienced a windy plastic “party house” and crawled backwards into a tunnel to see the hanging squid. I played rustic musical instruments, including maracas, or was it a rain stick, and did it matter which one? There were carefully considered imaginary worlds that reminded me of my childhood addiction to the View-Master, where I discovered that a wheel of three-dimensional slides could admit me into a world far more magical than the yellow walls of my bedroom.

This is PLAY—engaging in an activity for sheer enjoyment without forcing purpose or agenda. To this end, the exhibit may not appear to be as slick and managed as other art shows, but that is exactly the point. Teaching mentors for this exhibit, Angela Hottinger, Stashia Taylor, and Alecia Maher, speak passionately about the connection of play to art and how students, while working with craft and imagination, are able to visually communicate the happiness they feel. They use the word “joy” over and over again, and they mean it in the true vernacular of the term, which soothes the soul, rather than irritating the psyche.

‘Please Touch’

What is more, the exhibit was interactive. Signs begged students and adults alike to “Please Touch!” The journey through the exhibit was anything but linear. Participants moved back and forth from one experience to another, and in so doing, the experience became complete, between the message meant by the artist and the message received by the viewer, where everybody enjoyed and felt “something,” though not necessarily the same thought or emotion as the person preceding or following them.

One of our teachers suggested to me the text, The Meaning of Art, by Herbert Read. I am familiar with this writer, because he often refers to all of the arts as being the identifiers of the value of any civilization. He speaks eloquently about that value not necessarily being connected to a society’s military might or essential wealth, but rather to the gifts of its human beings—its philosophers, its poets, its artists. His credo in this book gracefully and precisely describes the beginnings, the processes, and the outcomes of our students’ work, through which they are presented with problem-solving challenges connected with the idea of PLAY, including how we interact with other human beings through a variety of materials and media. Read says:

“In expressing his intuition the artist will use materials placed in his hands by the circumstances of his time: at one period he will scratch on the walls of his cave, at another he will build or decorate a temple or cathedral, at another he will paint a canvas for a limited circle of connoisseurs.”

Like Read, our teachers believe that, while we cannot predict how a community will respond to the art we make, we must be confident, nonetheless, that its worth is well engrained in the fabric of humanity. Read speaks about true artists as being “indifferent” to the conditions or materials imposed upon them, and I certainly left the exhibit feeling like I could give our students a couple of sticks, a bag of tricks, a challenge in a bottle or box, and they would—they could—build that castle in the air and touch the minds and hearts of all of us.