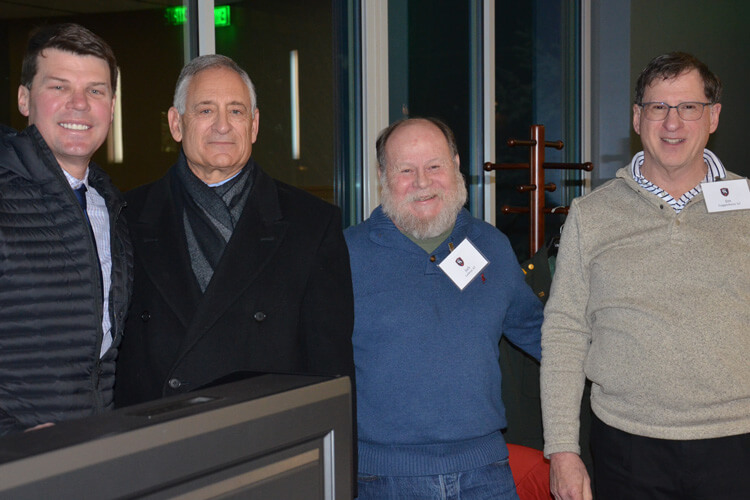

The Colorado Academy Alumni Back-to-School Night audience listened in rapt attention as three Vietnam veterans talked of their experiences before and during the often misunderstood struggle of the Vietnam War. Both Jack Leebron and Jim Guggenheim are Class of 1967 CA graduates, and their compatriot, Ralph Barocas, a George Washington High School grad of the same year. CA Head of School Dr. Mike Davis moderated the session and set the background for the evening’s discussion with a brief synopsis of Vietnam’s troubled history, stretching from an early Chinese occupation to the end of 35 years of U.S. involvement in 1975, spanning the presidencies from Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson to Nixon.

The hour-long panel discussion grew out of Davis’s Vietnam War history class, and his students and interested Upper School parents were invited to attend the session, along with alumni and alumni parents registered for the evening of “classes” that brought them back to CA on the evening of February 7, 2019.

The way we were

The veterans first talked about what high school life was like in the mid-sixties. Leebron, a boarding student from Oklahoma, reminisced about “sitting at the feet” of their excellent teachers, such as Frank Slevin, their English teacher, and likening the experience to the movie Dead Poets Society or, as his son pictured it, Harry Potter’s experience at Hogwarts. He also remembered Tap Tapley, who taught mountaineering, helped found Colorado Outward Bound on the CA campus, and led a rescue/recovery team of CA students on Mt. Blanca. Even with the Cuban Missile Crisis, protests beginning, and the outside world starting to impinge on CA’s realm, Leebron says the boys felt safe and sheltered. But just two short years following graduation, he found himself in Vietnam.

Guggenheim, a day student who entered CA in Tenth Grade, had similar feelings of being insulated from war. He mused, “Ours is the last generation that really believed what the government was telling us.” He remembered “duck and cover drills” in grade school and talk of needing to fight against Communism. He had a positive opinion of the military from his family history and a patriotic attitude that led him to participate in ROTC in college.

At Colorado State University, during Guggenheim’s first couple of years there, the student body was largely in favor of the Vietnam War. However, after the Tet Offensive, there was more opposition to the war; Abbie Hoffman came to talk to the student body; Kent State happened. Finally “Old Main” was torched by students, along with an ROTC facility, and suddenly, ROTC members were reluctant to wear their uniforms in public.

Barocas remembered George Washington H.S. as almost a prep school at that time: AP courses and a suburban demographic. Students were “wrapped up in cars, proms, and football” and didn’t pay any attention to the war until Senior year. He started off at Wyoming U., but flunked out, then watched his friends go to college, and he found himself in Vietnam at the tender age of 19.

He had enlisted in the airborne infantry and had been promptly shipped off to Ft. Lewis, Wash., where his head was shaved, it rained non-stop, and he had to get up at 4:00 a.m. and do whatever he was told. The transition was shocking, but “I liked it,” he admitted.

The shift from citizen to soldier was mostly a rude awakening for all of them. After attending a peace march in Ft. Collins, Leebron suddenly had the thought, “I can’t march if I haven’t been there.” He enlisted, was sent to Ft. Polk, Iowa, and was immediately put in charge of a group of men, because he could read and write. “Vietnam was a war for the poor people,” he said. “Affluent boys didn’t have to go.” He said Vietnam was as “mindboggling as anything you could run into.”

In country

Arriving in Vietnam via Ft. Bragg, N.C., the first thing that hit Leebron was the incredible heat. The second was the “smell of fear.” Always, since he was a combat medic, he was on patrol. Always, there was no safe place. The enemy was everywhere. “I got what I came for,” he said, “but more than I thought in my wildest dreams.” Some of these impressions he recorded in a book of poetry, Jekyll: A Medic Remembers Vietnam, which he published earlier this year. (His radio call sign was ‘Dr. Jekyll.’)

For Barocas, it was the oppressive heat, as well as the mud and rain when the monsoons came. “It was a shock to your system to be in that kind of environment,” he said. “You’re absolutely petrified on your first couple of missions.” The people and the countryside were impressed on his mind: “more archaic and more prehistoric than a third world country; no education, no schools; tight-knit villages, living in thatched huts.” The young soldiers were exposed to a situation beyond their strangest nightmares, but they were there to “help each other, to see the other guys got home, to make it through the night, and to see that their buddy made it through the night,” Barocas related. They weren’t yet 21; they couldn’t even vote. Barocas admitted, “It’s taken a long time to be able to talk about it.”

Changes in attitude and lessons learned

The panelists all noted a change in attitude from WWII to the Vietnam War. Barocas noted that U.S. citizens truly had a common cause in WWII. For instance, they all endured hardships and rationing. Boys and men wanted to enlist in the Army as their patriotic duty and privilege and were cheered and appreciated upon their return home; whereas, in the Vietnam War, “there was no unity, no common cause, no common thread. People did not have the respect that they had for WWII vets.”

Leebron added that the negative reception for Vietnam veterans at home was partially precipitated by “guilt by association” from the horrified reaction to the My Lai massacre and other reported atrocities. Military personnel were required to wear their uniforms while traveling, but people spat on them and called them “baby killers.” “It was only after they welcomed back soldiers from the Gulf Wars that they started thanking Vietnam vets for their service,” he noted.

What was the lesson, the meaning of it all? Leebron answered, “We were not over there to help the South Vietnamese. We were there to stop the Domino Theory, to stop Communism.” Barocas added, “Kennedy wanted troops out of Vietnam before the next election, but he was killed….The war was money for the military/industrial complex; it became about money, not idealism.” Leebron concluded, “There’s no accounting for the stupidity of governments.”

Guggenheim agreed, saying, “You can’t always believe what your government’s telling you.” And Barocas summed up with, “Pick your fights carefully. Be careful who you go after. When we put young people in harm’s way, we’d better be damn sure that’s the right thing to do!”