For more than a year, Colorado Academy Head of School Dr. Mike Davis has been speaking to students, faculty, families, and other education leaders—really, to anyone who will listen—about the need for schools to respond more urgently to the dramatic advances in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) that have captured headlines around the world by enabling tools like ChatGPT and Dall-E to craft essays, art, and computer code that’s all but indistinguishable from human-authored work.

“The rise of such powerful software will inevitably change the way we do business,” Dr. Davis has said. Students are using AI, and there’s no going back. “But we are fooling ourselves if we believe that students haven’t had access to tools that allow them to cut corners since the expansion of the internet.”

The real challenge, he goes on, is not fighting against the extraordinary power of AI, but instead creatively envisioning how access to AI is going to enhance teaching and learning. “I urge my fellow educators to take a deep breath and remember our shared goal: teaching students to use technology with integrity and sophistication in order to hone their own skills and critical thinking abilities.”

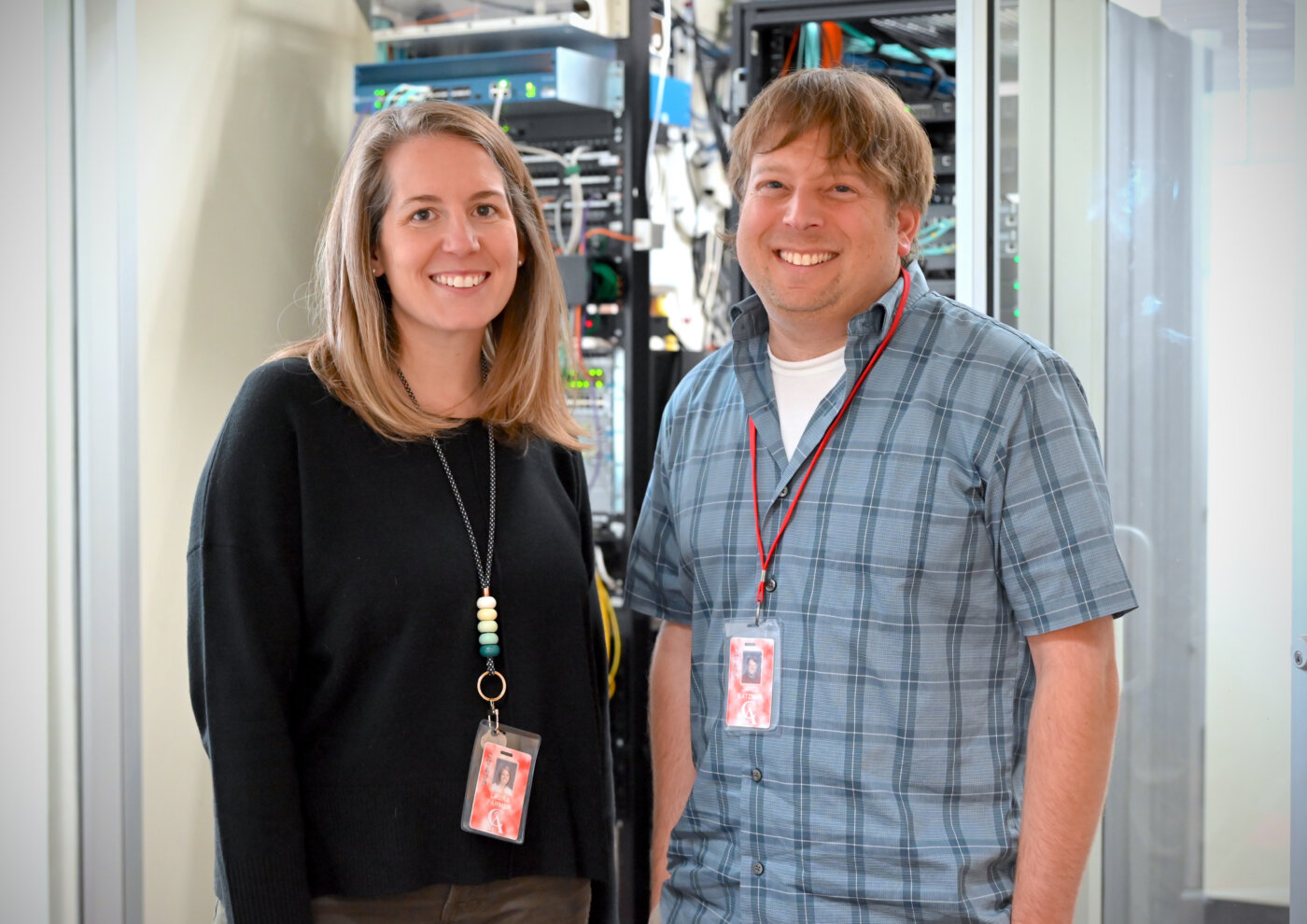

Behind the scenes of the debate about AI in education—both nationally and here on campus—CA’s Technology Team has been working to put together formal policies and classroom best practices to enable that creative and constructive approach to the powerful generative platforms now available instantly to almost anyone. Their efforts are leading the way for not only the CA community, but also other schools in Colorado and around the country, many of which are still in the earliest stages of addressing the questions that the technology raises.

“AI will be part of our students’ lives forever,” argues Director of Technology Jared Katzman, “so this is not something that we can ignore.”

Adds Director of Educational Technology Laura Farmer, “We want to encourage our students and teachers to understand and mindfully embrace AI in ways that make sense in a given situation—just like any other technology.”

To that end, Katzman and Farmer have collaborated with faculty members and administrators to craft a written “AI policy” that seeks to balance caution with openness and curiosity. It’s based on draft documents distributed by NAIS and ATLIS, the National Association of Independent Schools and the Association of Technology Leaders in Independent Schools.

“Submission of work that uses or is edited or aided by unauthorized or uncited artificial intelligence (AI) technology as one’s own work is considered a violation of CA’s academic integrity policies,” the statement begins.

At the same time, it acknowledges, “Teachers may provide specific guidance or requirements for the use of AI on specific assignments. When used appropriately, AI can support classroom learning under the following guidelines: Students take full responsibility for AI-generated materials as if they had produced them themselves. Ideas must be attributed, and facts must be true. Students are expected to develop their own understanding and knowledge of the subject matter and demonstrate mastery in their own voice. The use of AI tools as a learning aid should be for reference purposes only and is not a substitute for original ideas and/or thinking.”

In other words, explains Farmer, “We support a mindset that’s both pro-teacher and pro-student. Teachers are the ones who can guide students in their use of AI. And we know that there are so many ways students can approach AI as a powerful learning tool.”

From helping to generate a study guide to providing historical context around a particular work of literature on a class syllabus, “Students can use AI in ways that have nothing to do with getting it to write an essay for them,” she says. “We want to move away from thinking of AI as a means for ‘cheating,’ and toward viewing it as a way to be more informed and more creative.”

Understanding AI

Katzman, Farmer, and their teammates have developed training and curriculum to bring both students and faculty up to speed on the latest developments in AI and proselytize a constructive, rather than fear-based, approach.

That starts with educating the CA community about what AI is, and what it is not.

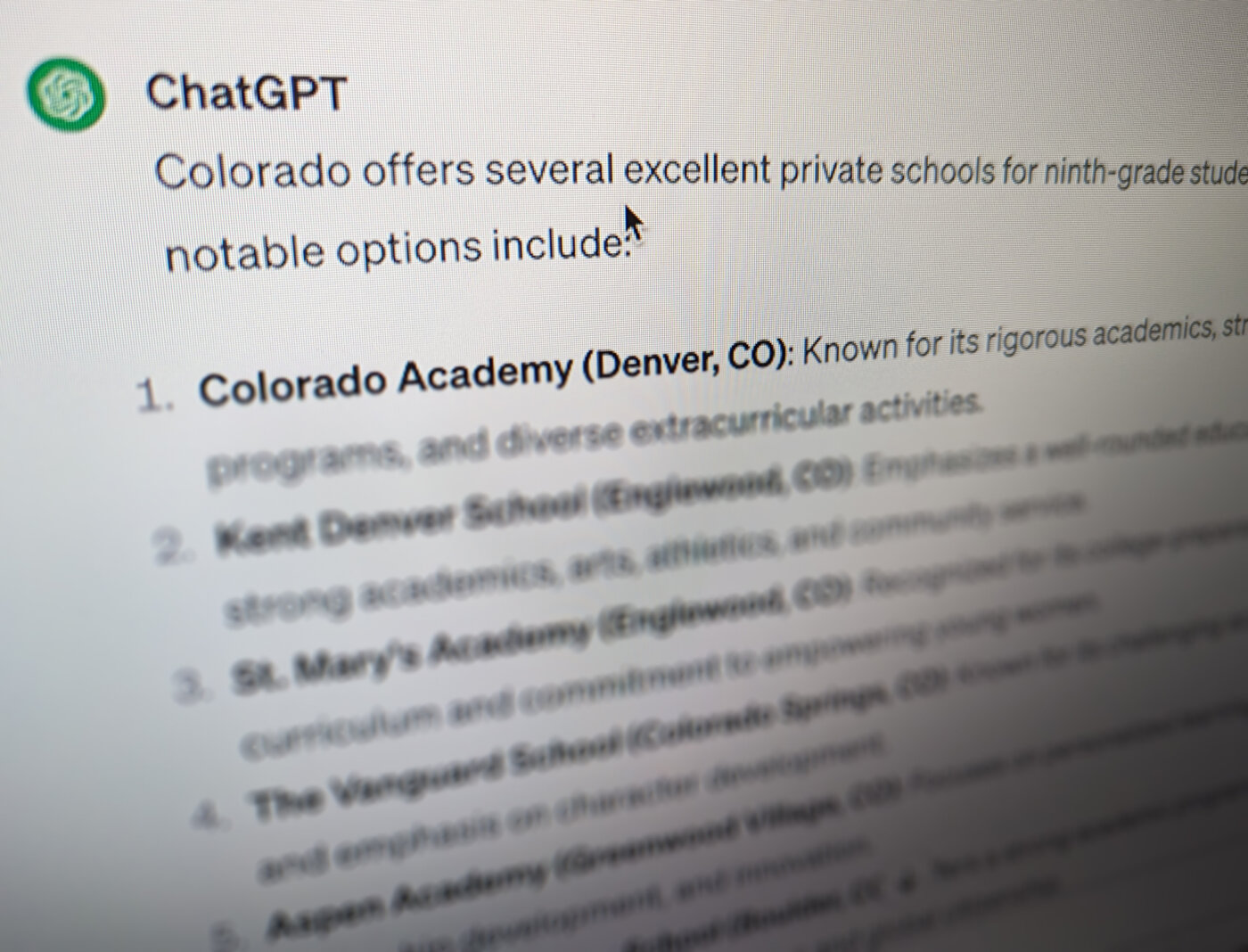

“Asking an AI to answer a question is fundamentally different from ‘Googling’ that same question,” explains Katzman. Whereas a search engine returns answers pulled directly from content that’s already been published and, hopefully, vetted online, AI tools like ChatGPT are actually synthesizing novel responses based on the enormous data sets in what’s called a large language model. These deep-learning algorithms can recognize, translate, predict, and generate text or other content based on analyzing the connections among trillions of words, images, and concepts contained in their training data.

The output they produce, whether a brief response to a simple how-to question or a full-blown essay made up of multiple paragraphs, often sounds surprisingly “human.” While they’re based on mathematical predictions about how things fit together—from words and ideas to colors, shapes, and even brand logos—they’re delivered with a seemingly authoritative command of facts, natural language usage, and realism that could convince almost anyone of their infallibility.

But “hallucinations,” when AI presents entirely fictional or simply bad information as fact, are just one of the ways that the predictive abilities of large language models and related systems can lead users astray. AI can increasingly create photorealistic images depicting events that never happened, and they can even produce voice samples, music, video impersonations, and other real-seeming artifacts that have the potential to mislead or cause actual damage.

Starting in Fifth Grade, students learn about the power and pitfalls of this kind of computing as part of CA’s digital citizenship curriculum, which emphasizes responsible use of technologies like school-issued iPads and applications such as TikTok and Instagram. Many of these Lower Schoolers already have experimented with AI with their parents’ supervision, and, says Farmer, they’ll be growing up in a world where its use is even more pervasive than it is now.

The result, she says, is that “We’re really thinking about the complete ‘scope and sequence’ that’s needed all the way from Middle to Upper School to ensure our students are equipped with the knowledge and tools to effectively use this technology. How do you engineer an AI prompt to produce the results you want? How do we determine the accuracy of what an AI tells or shows us? What are the subtle signs that can sometimes reveal something’s been generated by an AI instead of a human?”

With teachers, CA’s Technology Team has led professional development sessions that delve into the remarkable advances in sophistication that arrive seemingly every few months with generative models such as GPT-4, and that detail the potential pitfalls around the use of AI in education, such as bias in the training data, threats to students’ privacy, and the near-impossibility of detecting AI-generated student work using currently available tools.

“What we’re actually telling teachers,” says Farmer, “is not to look for ‘gotcha’ moments. The so-called AI ‘detectors’ out there are just not effective enough for that today.” Instead, Farmer and her colleagues are working to ensure that every teacher on CA’s campus has first-hand experience with AI—effectively creating text prompts to generate essay responses or images, for example—so they can envision its limitations and possibilities.

“Many of our faculty members are now diving into the process of determining how AI fits into their classrooms,” Farmer relates. “They’re realizing that the questions we’re asking when we’re evaluating an AI’s responses—Is this accurate? Is there bias? Is this high-quality work? Did I ask the right question?—are, in fact, the questions we want our students asking about their learning every day.”

Practicing how to “talk to” an AI and then judge its responses—perhaps even submit feedback or reword the prompt in a better way—hones fundamental skills that pay off in every discipline, even when AI isn’t even part of the discussion.

AI in the classroom

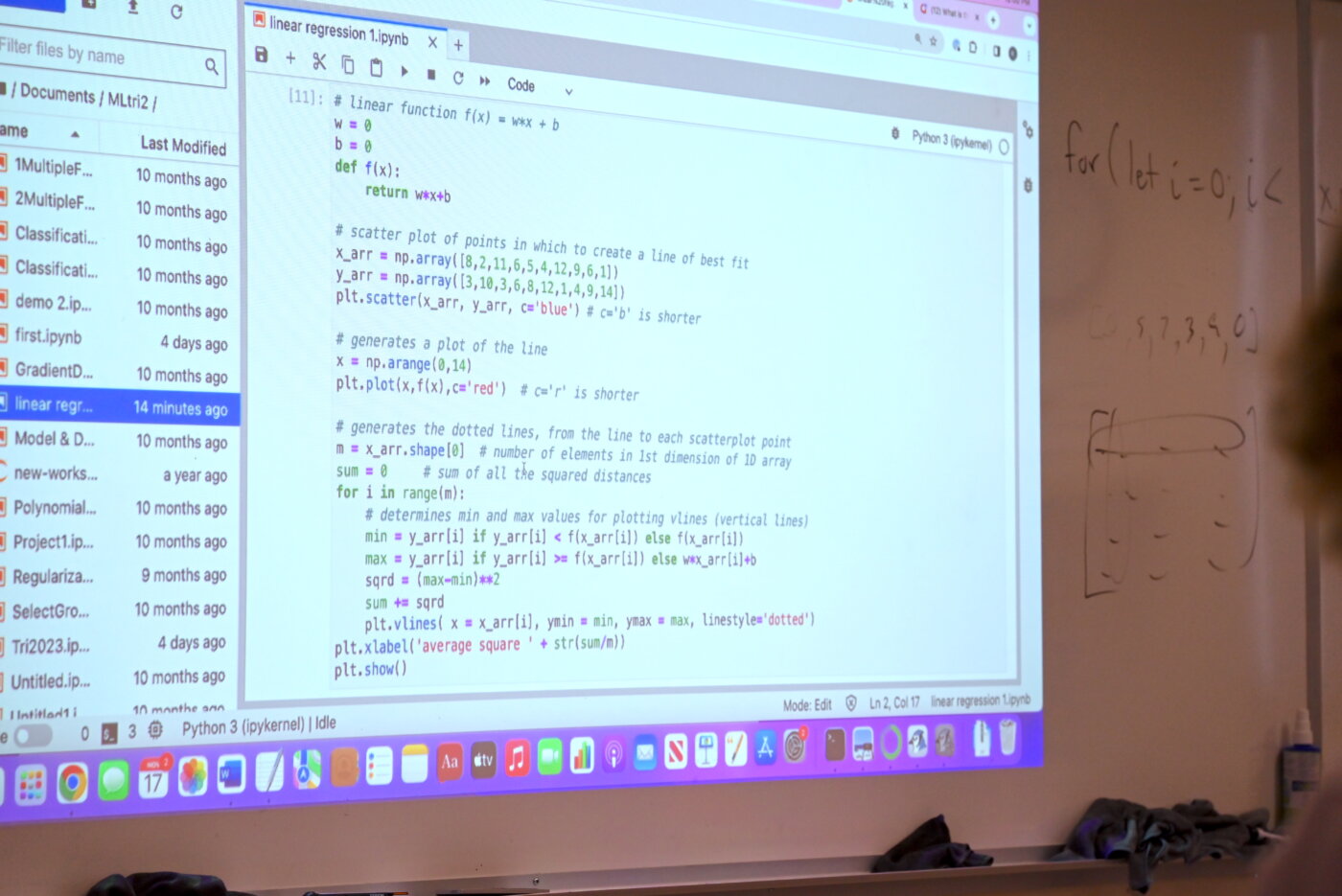

Still, for computer science instructor Kyle Gillette, who teaches the ASR (Advanced Studies and Research) course AI and Machine Learning, AI is almost always part of the discussion. His advanced offering for Juniors and Seniors represents CA’s most direct engagement with AI, where students examine the foundational concepts and technologies that coax human-seeming understanding from gargantuan data sets and thousands of lines of code written in languages such as Python and C++.

Machine learning, or ML, Gillette explains, is a subfield of artificial intelligence focused on training algorithms with data sets to produce learning models capable of performing complex tasks, such as sorting images, forecasting sales, or analyzing big data. ML is “the primary way that most people interact with AI,” he says.

Consulting an online chatbot to troubleshoot a problem or using a virtual assistant to schedule a meeting are instances of ML. So is the amazing ability of an application like Dall-E to generate painterly or photorealistic images based on text inputs, or the incredible power of a healthcare application to interpret patient X-rays or health histories to diagnose or predict disease. “In each case,” underscores Gillette, “my students learn that most of what we understand as AI is built on machine learning, which gives a computer rules for identifying patterns in data and actions to take based on those patterns.”

Why is this so important? Because, as Gillette explains, knowing how AI reflects the data on which it’s been trained is fundamental to weighing some of the biggest questions the technology raises. The months-long strike by the biggest American actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA, he points out, was sparked in large part by the emerging power of AI models to recreate the faces, voices, and movements of human performers whose talents serve as their training data—even without their permission.

“We are at a new frontier,” Gillette states, “where someone with an idea can do almost anything they can conceive of. In mathematics, we used to be astonished when someone would discover something new perhaps once a decade. But in computer science today, that happens all the time.”

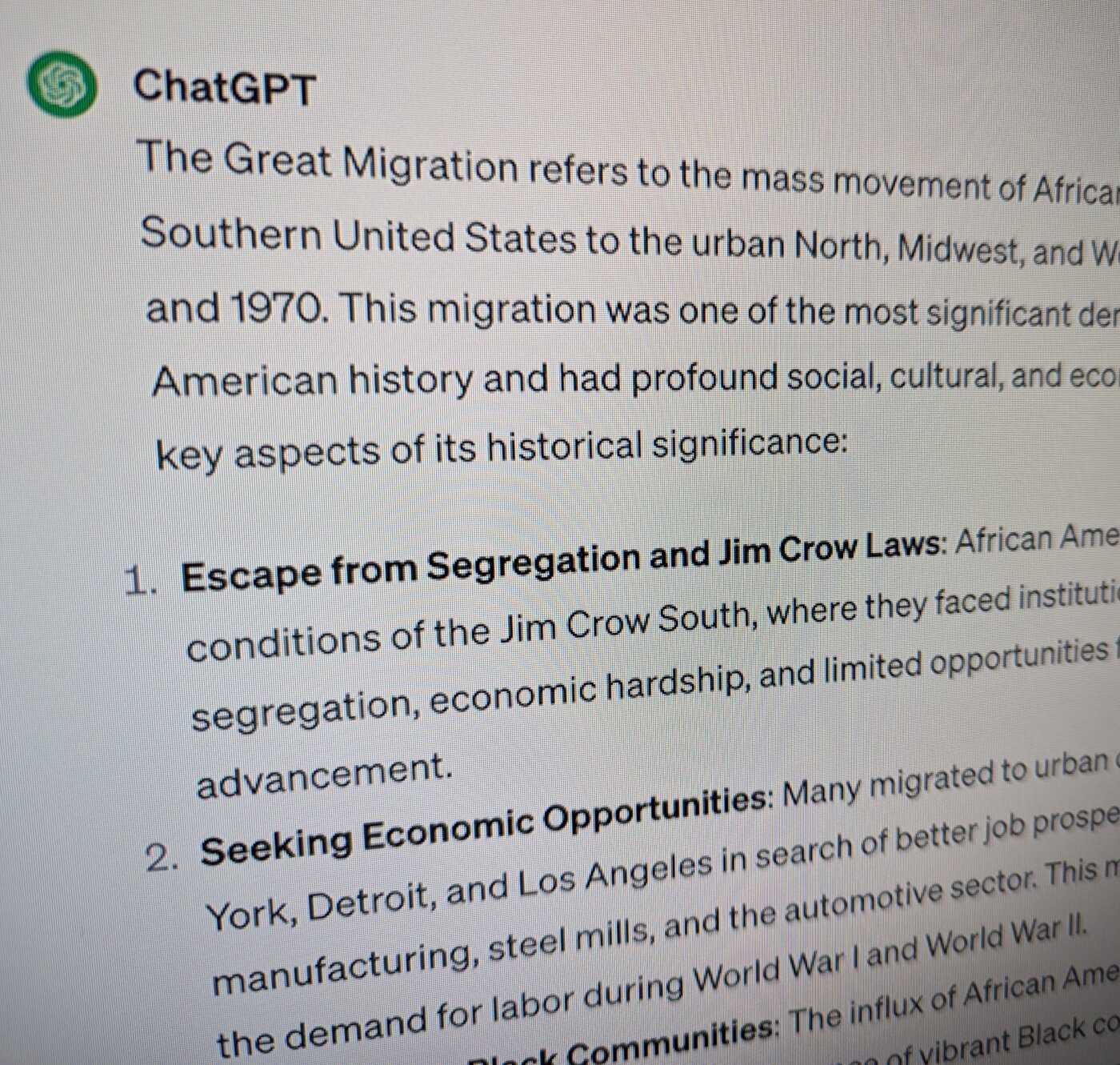

Meanwhile, in the Upper School English Department—where truth and meaning are of no less critical concern—students make use of AI’s powers of synthesis to dig into the ideas and historical context surrounding the works they study.

In American Literature, students read the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, whose antislavery oratory and writings made him the 19th century’s most important American civil rights leader. Learning that Douglass was an early proponent of photography as a tool for political change, students prompt ChatGPT or Google Bard to provide further details about the evolution of photography during his lifetime, and they consider how photos—including those created whole-cloth by an AI tool—can influence our beliefs today.

In the Honors course Literature of Work, students study a variety of texts that dramatize labor, asking questions about how work shapes our identities and lives. Inevitably, they ponder the ways that generative AI—with its uncanny ability to produce convincing prose and synthesize data—may fundamentally change work itself, and consequently our understanding of ourselves.

Elsewhere, CA students are turning a more critical gaze on AI technology. Middle Schoolers compare AI-generated lab report templates to their own original reports to gain a sense of where AI falls short and what it means to generate high-quality scientific work. And in Fifth Grade, students researching the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans moved from the South to the North in the early part of the 20th century, look at AI-authored summaries of this turning point in history to see if they can detect bias or other inaccuracies.

But AI’s capabilities are only going to improve and become more pervasive, argues Farmer; those challenges we encounter today will likely disappear in a matter of months. That’s why, she insists, schools like CA have such a pivotal role to play in educating a new generation of “AI natives.”

“They’re going to be confronted by AI whether they want to or not—whether they realize it or not. It’s already in their phone; it’s in the Google Docs they’re creating for school.”

Until now, adds Katzman, AI’s ability to generate written material has been center stage. But in the very near future, AI tools will begin making a potentially bigger impact in math, science, speech and music analysis, and the visual arts. “In a period of such rapid change, we as a school have to push the boundaries of what we’re teaching about this technology,” he says.

Ultimately, Katzman and Farmer agree, AI has the potential to bring sweeping improvements to the world of education. Imagine creating class schedules for CA’s 1,000-plus students using an AI model: A tremendously time-consuming, imperfect exercise becomes a “one-and-done” process that benefits teachers, students, and families at the touch of a button.

Or, they go on, picture students in an English, coding, or art class running early drafts of their projects through an AI “reviewer,” receiving multiple rounds of detailed feedback on style, technique, balance, and effectiveness as they rapidly iterate on their works in progress before finally meeting with the teacher for the kind of holistic, responsive, and, yes, time-consuming support that only an expert educator can provide.

“Research tells us ongoing, instantaneous feedback can be a tremendous boon for learning,” explains Farmer, “so many of us in schools are thinking about the ways that AI can add value to what a skilled teacher can provide, at the same time leveling the playing field so that more students can benefit from deep, personalized coaching.”

We may not be able to predict everything that AI is going to change in the future, argue Katzman and Farmer, but we can do our best to stay ahead of the game that’s surely going to change the world.