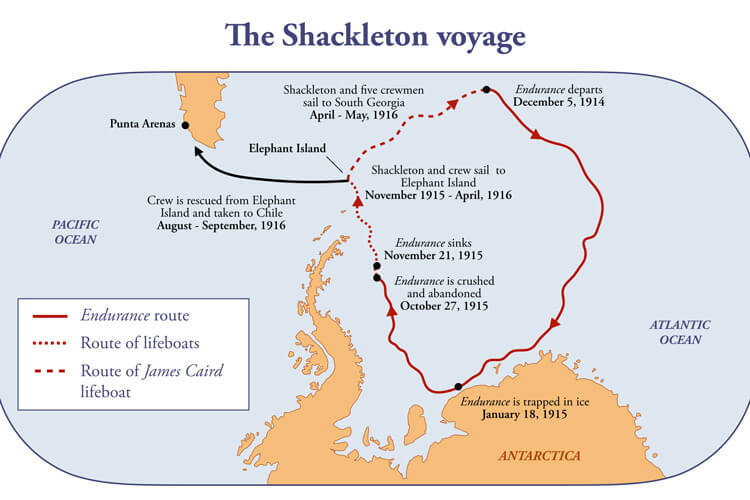

Recent news of the discovery of the wrecked hull of the ship Endurance, deep in the waters of the Antarctic Ocean, captured my attention. Adventurers and scholars of leadership know that the Endurance is synonymous with the famed explorer, Ernest Shackleton. In August of 1914, Ernest Shackleton set out with 27 men to make the first transcontinental crossing of Antarctica. On the way to Antarctica, Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, got stuck in ice in January of 1915. The Endurance drifted with the ice for months, until that November, when ice crushed the wooden ship. What followed was an epic journey across the ice to Elephant Island, where most of his crew stayed, while Shackleton and a few other men made an 800-mile open-ocean journey in a 22-foot craft to a whaling station at South Georgia Island. Then Shackleton returned to Antarctica to rescue the sailors he’d left on Elephant Island. Amazingly, everyone on the expedition survived, primarily because of Shackleton’s leadership.

Imagine not only being stuck in ice in sub-zero conditions, but also drifting on that ice away from your destination, and then realizing over time, that the pressure of that ice was slowly crushing your only means of escape. Shackleton, by this point in his career, was already an accomplished explorer. He had been on two previous expeditions, and had come closer to the South Pole than anyone before the Norwegian Roald Amundsen located the South Pole in 1912. Shackleton’s expedition set an ambitious goal of crossing the entire continent. But he was in a hurry and ignored advice about getting stuck in the Weddell Sea. Some speculate that he knew that the predicament he and his men were in was his own fault, and thus he shifted his focus from exploration to survival.

Shackleton was adept at shifting his priorities and goals in the face of changing conditions. He recognized that he had to inspire his crew and set a positive example. Sir Edmund Hillary, the famed climber of Everest, once wrote: “Danger is one thing, but danger plus extreme discomfort is quite another. Most people can put up with a little danger—it adds something to the challenge—but no one likes discomfort.” The crew of the Endurance certainly experienced discomfort. Shackleton worked to keep morale high. He kept the men focused as they toiled to free their ship and then eventually to carry thousands of pounds of supplies with them on their journey to safety. One of his crew noted, “I found him rising to his best and inspiring confidence when things were at their blackest.”

Shackleton also had to demonstrate flexibility. He led from the front, sharing the burdens of his men. He had to model courage, not only getting his men to Elephant Island, but then braving an ocean journey in which his navigation skills had to be perfect. After arriving at South Georgia Island, he did not waste a moment to get back and rescue his men. In the face of a failed expedition, he put others first. Another member of the crew reflected, “He was essentially a fighter, afraid of nothing and of nobody, but [also] human, overflowing with kindness and generosity, affection and loyal to all his friends.”

When I was young, I spent time with another famous explorer, Dr. Laurence McKinley Gould. Gould was a geology professor at the University of Arizona and my father’s colleague. He was born in 1896 and, in 1929, was the second person to reach the South Pole and confirmed Amundsen’s achievement. Gould was chief scientist of Admiral Richard Byrd’s American expedition to Antarctica. While Byrd attempted to fly over the South Pole, Gould led a five-man, 1500-mile dog-sledge journey to the South Pole. For more than two and half months, Gould mapped the geology and glaciation as he and his dogs traveled to their destination. He called Antarctica “a veritable paradise for a geologist.” As a child in the 1970s and 1980s, my brothers and I would periodically visit with Dr. Gould. It’s important to remember that Gould was on the last expedition that arrived in a sailing ship and used dogs for travel. His house was like a museum of early 20th century polar exploration: snowshoes, a four-foot stuffed penguin, and historic photos. When he would talk about the expedition, he would always bring up the dogs. Many of the photos on his walls were of the dogs. In 1999, the American Museum of Natural History had a wonderful exhibit on the Shackleton expedition. It, too, had amazing photographs of the men, their predicament, the Endurance in various stages on the ice, and the dogs.

This recent news of finding the Endurance brought back a flood of memories about my childhood, had me reflect on my own interest in exploration, and renewed my interest in Shackleton. It also brought a recognition of how his story connects to Colorado Academy’s mission. When we revised our mission statement, we intentionally crafted the words, creating “curious, kind, courageous, and ADVENTUROUS learners and leaders.” Adventure is an important part of any life. We can be adventurous in many ways. I hope Shackleton’s story inspires you to learn more and even try a new experience.