When she was an elementary student in the city of Tai’an, China, in the eastern part of the country south of Beijing, Colorado Academy’s Upper School Chinese teacher, Ning (Julie) Wei, would stop by her father’s classroom in the local high school every day after she was dismissed. There she would do her homework and joke with the older students, whom she gave affectionate nicknames. Wei says that she recalls those days of visiting her father, standing at the front of his classroom, as “the coolest.”

It’s no wonder now that teaching, she says, feels like the most natural thing in the world.

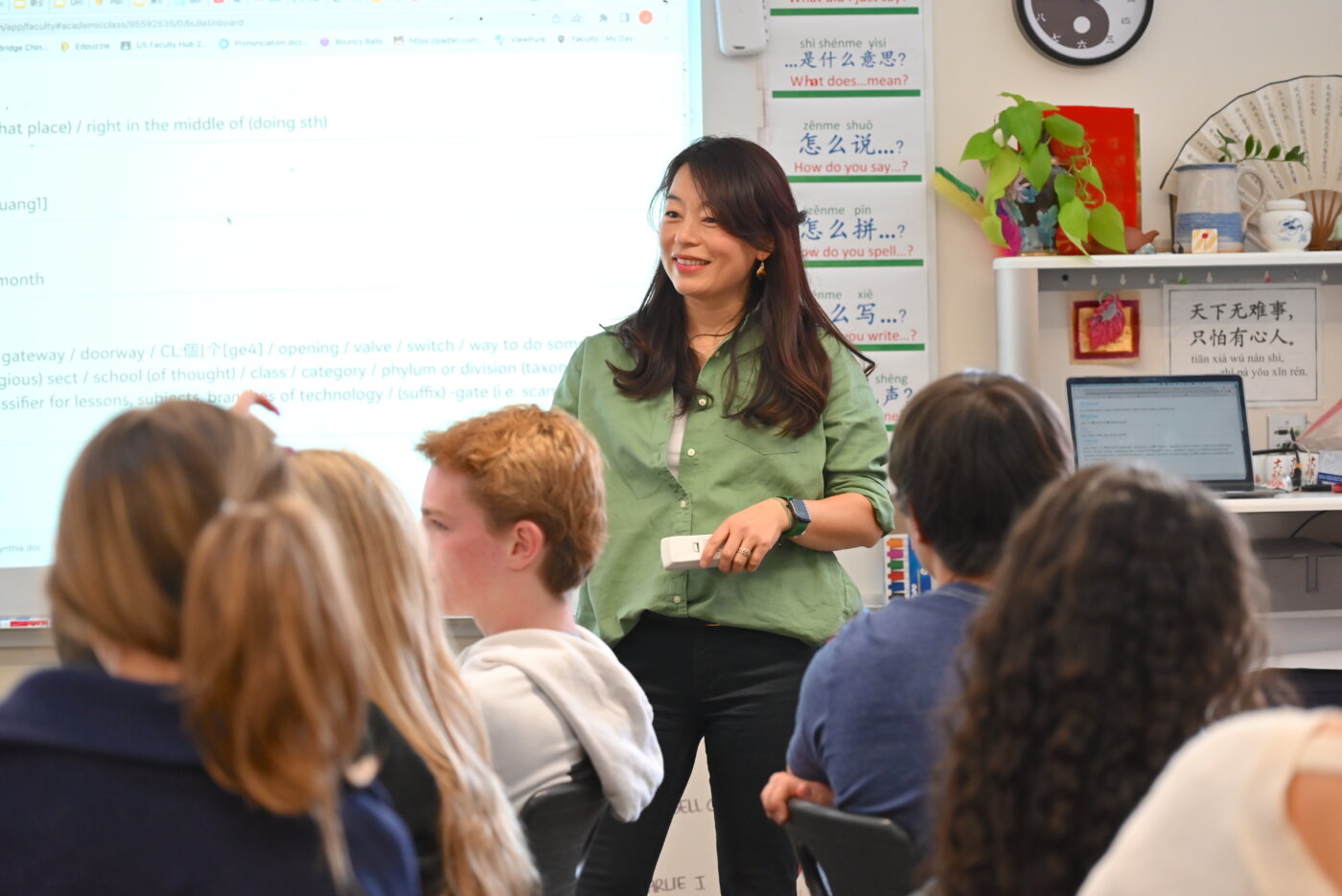

Recently named Teacher of the Year for 2024 by the Colorado Congress of Foreign Language Teachers (CCFLT), Wei is beloved by her students and respected by her peers for her authentic spirit, generous sense of humor, innovative approach, and tireless commitment to connecting people through the teaching of Mandarin Chinese in Colorado and beyond.

“Ms. Wei—known affectionately by her students as 魏老师 (Wei Laoshi—Teacher Wei)—is a builder of communities,” wrote Avery Lin ’20 in the student recommendation he submitted in support of Wei’s nomination for the CCFLT award. Lin, who studied Mandarin in Wei’s classroom for all four years in CA’s Upper School, continued, “She utilizes language education to bring individuals together. Students of her classes become drawn towards each other; initially by Ms. Wei’s bright, inviting, and witty personality, and later by the way she encourages and expects students to rely on each other in pursuing their own education. Whether students are working together to compose fictional dialogues or competing in team games focused on reading comprehension and character recognition, Ms. Wei’s teaching style fosters community and communication in the spirit of using Mandarin to build stronger human relationships.”

In her own letter of recommendation, Upper School Spanish teacher and World Languages Department Chair Lisa Todd added, “Her balanced approach of high expectations, supportive understanding, and genuine care for her students inspires them to always do their best. They consistently make a point to speak with her in Chinese, clearly delighting in their ability to carry on a conversation in their new language. When she and I are chatting together in the halls, we often must pause because a passing student wants a chance to exchange a few words with her—interactions which often culminate in her delighted laugh at something clever her student has said. The impact she makes is lasting: many of her alumni keep in touch and continue to use and study the language, which is the highest praise for a language teacher.”

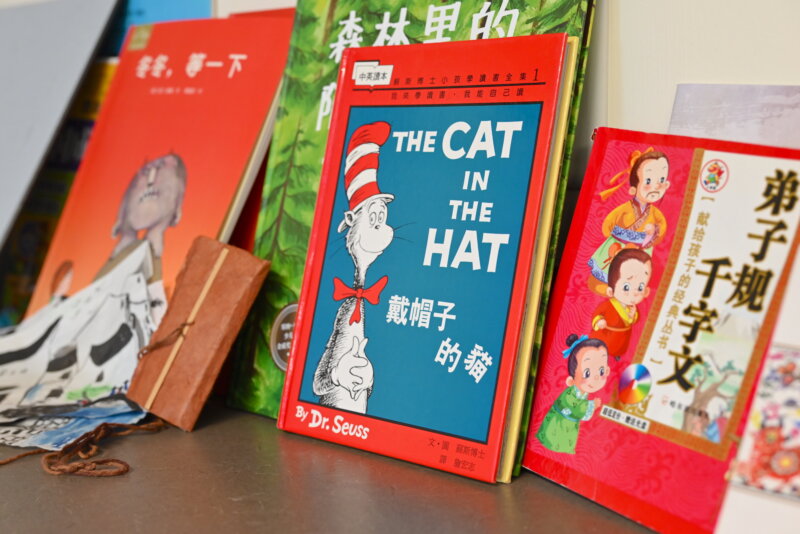

Anyone who has visited Wei’s classroom—with its rich collection of cultural materials, abundant laughter, and constant conversation in Chinese—would attest to the accuracy of these words of praise. But according to Wei, her teaching approach stems not from any extensive formal training as a language teacher (indeed, Wei earned two degrees in business and began her career in the field of public relations while in China), but from her willingness to constantly seek out new and better methods, exchange knowledge with Mandarin teachers around the country and across the globe, and engage her students intellectually and emotionally by sharing her passions and inviting them to share their own.

“In my teaching, I try different things all the time,” explains Wei. “If something isn’t working, I instantly switch; I’m flexible. Above all, I make personal connections with my students—they’re stuck with me for three or four years, after all! I don’t avoid hard conversations when something isn’t going well, but at the same time, my students know I really care about them. They get the sense, ‘Ms. Wei wants me to learn, and she wants me to do something with the language.’”

A global perspective

Since her arrival in 2011, Wei has vastly broadened CA’s Mandarin program, incorporating new units about Chinese popular culture, social and political issues, history, and traditional literature and art. She has forged global ties with high school and college teachers of Mandarin through WeChat, a messaging platform that is hugely popular in China. And she has become an authority in her field, hosting virtual professional development workshops for other teachers in her network.

“My motto is ‘Your classroom is small, but the world is big,’” Wei explains. “Today, we don’t have to go to China to experience Chinese language and culture—it’s everywhere: TikTok and Instagram, streaming movies and TV shows, news websites, Zoom classes, and many more. Anything that’s worth sharing can give students a whole new perspective on the world.”

Wei and her online colleagues have “visited” each other’s classrooms virtually, and this spring, Wei’s advanced students will have the opportunity to participate in discussions with college students studying Mandarin at the University of Virginia and Duke University. Wei may be a department of one at CA, but, she argues, “I probably have more connections with other teachers than some of my colleagues.”

In recent years, Wei explains, that network has served an even more vital purpose: enabling collaboration to combat the increase in anti-Asian violence that came with the COVID-19 pandemic. “During that time, Chinese teachers in the U.S. felt perhaps more strongly than any others that we had to do better at educating our students and helping to fight violence and bias—even though they felt their own fear and were unable to see their families in China.”

Building connections and awareness is the linchpin of her strategy to see that CA students understand a culture of which most have no firsthand experience.

“I have a huge advantage as a Mandarin teacher: I’m Chinese,” she says. “I watch all kinds of Chinese drama and reality shows, Chinese TikTok, YouTube—almost anything. Whenever I see something that makes me laugh or makes me think, I share it with my class. It doesn’t have to be something from a textbook. It’s authentic Chinese language, authentic culture, so we use it” Wei explains that she uses plenty of English-language materials as well. “I believe that whatever you know in English, you can also try to speak about in another language.”

Wei even maintains a class Instagram account of her own. Posting a fun picture and caption in Mandarin every day, she says, helps keep bonds strong even outside the classroom. Acknowledging a lesson she learned as a public relations professional in China, Wei says, “Connection is the key to all things.”

A creative approach

Though Wei’s lessons may be globally inspired and often freewheeling in their focus on music, pop culture, or contemporary Chinese society, she still must carefully fine-tune her teaching to the varied abilities of her students.

In Chinese I, the Ninth Grade class that fulfills the first of the three required years of world language study for all Upper Schoolers, Wei eschews the immersion approach that’s popular in some schools.

“My Ninth Graders go to five or six other classes on top of Chinese,” she explains. “They are tired. I don’t want them feeling frustrated that they don’t understand a word I’m saying; I don’t want to scare them away.”

Instead, Wei offers a gradual, spiraling path to language acquisition, teaching just a handful of words or concepts at a time, and then repeating those day after day in Chinese only to build her students’ working vocabulary.

“It adds up quickly,” she says. “And because I am their only Chinese teacher, I always know what they can understand—I never have to ask them what words or topics they may have covered in another class. I am able to use what each student already knows, and that builds their confidence. Little by little, they become prepared for deeper study.”

By Chinese III and IV, in students’ Junior and Senior years, Wei teaches almost entirely in Mandarin, and she expects classroom conversations to be conducted mostly in the language, as well. And in her Advanced Seminar and Advanced Topics honors courses, students are asked to speak and write authoritatively and insightfully in Chinese about topics that range from ancient and modern literature to current events.

Earlier this year, Advanced Topics students studied traditional Chinese “idiom” stories, ancient, well-known tales that gave rise to popular Chinese expressions such as “Beat the grass and startle the snake (打草惊蛇).” The class is currently looking at pop culture through Chinese television shows, and by the spring the students will be creating their own projects, such as one Sophomore’s blog in Mandarin dedicated to her passion: fashion. “I’ll help her promote the blog among Chinese speakers,” explains Wei, “and we’ll see where it goes from there.”

Honoring tradition despite changes

It’s not just those in Wei’s most advanced courses who stop her on campus for a quick Mandarin conversation like the one Todd mentioned in her letter of recommendation to CCFLT. Recently, a Junior Chinese III student encountered Wei at the Ponzio Art Center, and they casually discussed in Chinese the art project that Wei was having her students complete in honor of Chinese, or Lunar, New Year.

“He said, ‘I just love talking in Chinese on campus,’” Wei relates. “’Nobody knows what we are saying. This feels so cool.’”

The art project in question had students practicing their calligraphy as they carefully wielded traditional brushes and ink to print new year’s wishes and proverbs onto special red paper decorated with images of a phoenix and a dragon. The calligraphy, says Wei, was a chance for students to get more practice hand-writing Chinese characters—a skill whose importance has evolved in recent years.

“In China,” Wei explains, “writing everything by hand has become less and less common. Everyone types. In my classes, I began to notice how much of their Chinese handwriting my students were always forgetting because there just wasn’t enough time to practice.”

Wei attended an online workshop about the relevance of handwriting in Chinese language instruction, and after hearing professors from Yale and George Washington universities recount how much more quickly their students progressed when they switched to typing in Chinese rather than writing by hand, she began to change her own teaching practice.

“The students who focused on only listening, speaking, reading, and typing had so much more time to get into interesting topics—it just made sense for me.” When Wei changed most of her assessments to require typing instead of handwriting, students felt that a “burden” had been removed, she says, and they were excited to spend more time having conversations—the core of her methodology.

But Wei, who admits that writing is her favorite piece of the language, is determined to keep the art of printing elegant Chinese characters alive at CA, noting that many of her students choose to study the language precisely because of the beauty of written Chinese. Last year, Wei had all of her classes collaborate to create a giant dragon made from hundreds of colorful Post-It notes, each featuring a handwritten Chinese character. Students outside of her program, as well as faculty members and even Head of School Dr. Mike Davis, were invited to try their hand at writing out a character for the project. The final masterpiece hung in the CA Dining Hall for months, where students in all three divisions of the school could enjoy it.

Wei notes that in none of her classes does she ignore the problems that China is dealing with. At the same time, her commitment to not only teaching the Chinese language, but also celebrating China’s culture and history—and the ways we may all find some connection to them—may be what most distinguishes Wei as a teacher, and what most clearly affirms her selection as a teacher of the year.

Certainly, it is what keeps so many graduates of Wei’s program involved with Chinese language study into college and beyond. According to Wei, many of her former students make Chinese their college minor, if not their major. One, Julie Marwan ’22, recently got in touch to share news of the Chinese class she had enrolled in at George Washington University. When Wei heard the name of Marwan’s teacher, she realized she knew the professor from an online workshop, and messaged her to chat about her former student.

“I heard you have my student from last year—Julie,” Wei told her.

“Yes, she’s wonderful,” the professor replied. “Thank you for teaching her so well!”