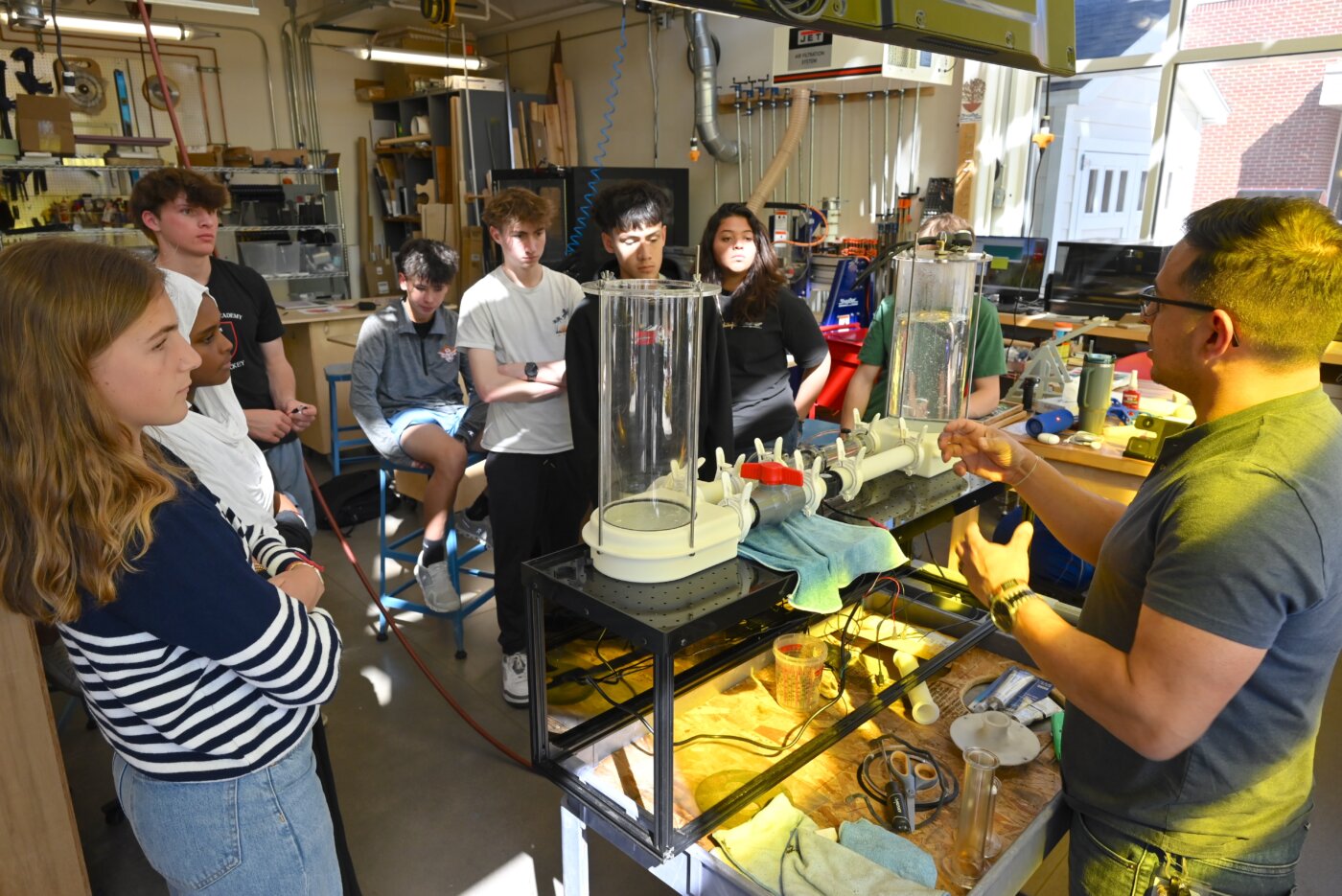

It was not really a surprise when, one day early this year, a custom-made left-heart-ventricle simulator appeared in the Anderson Innovation Lab at Colorado Academy. The Lab’s director, Upper School Engineering and Design Instructor Dr. Márcio Forléo, had constructed a similar machine while completing his PhD in bioengineering at Colorado State University, and worked in research and innovation with leading medical device companies before coming to CA in 2023.

The new heart simulator, which he designed and assembled almost entirely with his own 3D-printed parts and industrial grade valves and electronic components, is a huge improvement on the one he built years ago at CSU. “That one was mostly made with stuff from Home Depot,” he says. “It was ugly.”

Far from ugly, and roughly on par with commercial biomedical testing technology, the sleek machine now standing in CA’s Innovation Lab hints at the many ways the space and its innovative curriculum have continued to evolve with Forléo at the helm. Over the past two years, he and his colleague, Engineering Coordinator Ian Marzonie, have transformed a largely traditional “makerspace” heavy on wood- and metal-working into a high-tech hub for experimenting with a variety of materials and technologies and a deep emphasis on computer-aided design (CAD).

The heart-valve simulator plays a central role in the latest trimester elective Forléo’s added to the expanding Upper School engineering and design curriculum: Biomedical Engineering, a unique second-level course that students can choose after completing his Introduction to Engineering Design offering.

The new elective, Forléo explains, is, in fact, modeled on the process a biotech startup company would follow to design a novel prosthetic heart valve. “The students go through the entire product lifecycle, similar to what’s laid out by the FDA or Europe’s ISO Standard,” he says. The student-engineers start with lessons in anatomy and physiology, then proceed to an examination of user needs and research the properties of various materials. Finally, the students fabricate and test prototype valves in Forléo’s simulator, which can accurately reproduce the pressurized flow of blood around the body (the machine’s “blood” pressure even measures a healthy 120/80).

Adding the new course to a curriculum that already includes an introductory offering as well as intermediate and advanced engineering and fabrication electives is “a bit of a Trojan horse,” Forléo acknowledges. “We have so many high-achieving students here at CA who are looking to go into fields like medicine. By tempting them with the engineering side of the field, we’re affording them a whole new way to envision their career path.”

Throughout his own career in the biomedical industry, Forléo continues, he collaborated with scores of doctors and surgeons to develop new devices. The very best of those were the ones who had a background in engineering, too, he says. “When I’m working with a medical professional, and we’re trying to figure out a new design—what’s working in the body, what’s not working—if they can understand the engineering side, our discussions can be much more productive; they can ask the right questions, and they can grasp the answers.”

Another bonus inherent in the biomedical engineering field is its proven appeal to female-identifying STEM students. “The reality is that working with laser cutters and welding tools isn’t for everyone,” explains Forléo. “By emphasizing the medical side, we can attract students who might otherwise not consider a path in engineering.”

Fail forward

The opportunity to awaken students’ passion for engineering and design through ideas they may have never encountered before is the primary reason Forléo moved from a lucrative career in industry to a high school teaching position.

“I love meeting kids at a point in their lives where they might not have spoken to anyone about this field before. Innovations like the transcatheter aortic valve replacement—which incorporates metal components with shape ‘memory’ to treat restricted blood flow—immediately spark so many questions. I can see their minds just opening up.”

That thirst for knowledge naturally segues right into the engineering design process which is central throughout the curriculum, says Forléo. A cousin of the Design Thinking philosophy in practice throughout CA classrooms, the engineering design process requires innovators to follow a series of iterative steps in order to determine objectives and constraints, prototype, test, evaluate, and refine their ideas on the way to developing functional products.

In the Innovation Lab, “Students don’t just get to jump into creating something, no matter how eager they are to get started,” Forléo asserts. Instead, they must create a proposal, detailing how their product works and what need it fills; students have to describe the processes and tools they’ll use, as well as the materials and budget they’ll require. Only then are they permitted to begin brainstorming and prototyping.

This year, that rigorous process has helped students turn out an impressive array of final projects, from a go-kart to a clock with custom-fabricated internal gears, and from a laser-cut miniature greenhouse to molds for carbon fiber components.

“So many students come into this space ready to start building,” recounts Forléo. “But they quickly discover that that always comes back to bite you.”

Not that that’s necessarily a bad thing: Forléo emphasizes that failure is an essential ingredient of effective engineering design.

“One of the things that I constantly repeat to my students is, ‘You’re going to mess up.’ But I’m very clear that when I talk about making mistakes, the point is to ‘fail forward.’ I want my students to learn the importance of resilience and taking something useful away from every failure.”

Forléo often repeats the half-apocryphal story about the inventor Thomas Edison, who once described to a reporter the challenges of engineering the light bulb: “I have not failed 1,000 times to build a light bulb. I’ve succeeded in proving 1,000 ways how not to build a light bulb.”

Graduate student colleagues from his CSU days, who now work in the industry or chair their own engineering departments, Forléo says, underscore a similar point. “Apart from physics and calculus, the academic prerequisites for anyone interested in pursuing engineering in college, professionals in this field will tell you that the other, equally important skill required is being willing to break things—to thrive on repeated trial and error.”

Engineers who get things right on the first try? They don’t exist, he insists.

The value of breaking things

The college model of the engineering design curriculum grounds Forléo’s planning for the growth of CA’s program, too. He aims to introduce a yearlong, single-project-focused elective akin to the Senior Portfolio ASR course in the Visual & Performing Arts Department, in which students devote an entire school year to producing a body of advanced creative work, to be displayed in a culminating final exhibition.

In a college engineering program, Forléo explains, students finish most of their required coursework by their junior year, at which point they embark on a major design project during their final undergraduate year. Students often work with an outside company or engineering professional to complete their capstone, which in effect serves as a sort of internship.

“I’d like for us to mimic that a little bit,” says Forléo, “perhaps by having our students work with a business or community group, with a final showcase where they get to demonstrate what they’ve created.”

But he’s under no illusion that all of his engineering design students, even the most dedicated, will pursue the same notoriously difficult path at the college level. Those who do, he says, will feel well prepared after completing CA’s program; but those who branch out into medicine, environmental science, the law, or almost any field imaginable will be just as ready for the challenges they will encounter. After all, breaking things—taking them apart to see how they work—is a learning mode that works just as well with a novel or historical epoch as with a medical device.

That Biomedical Engineering attracted such a long waiting list of students when it was announced that a second section was added to the schedule proves the broad, enduring appeal of this approach. So does the bustling Anderson Innovation Lab itself, busy on any given day with such a diverse range of student projects that Forléo and Marzonie are constantly on the move, doling out suggestions and advice to one student-engineer after another.

The extraordinary thing about this field, reflects Forléo, is that the moment you begin to understand it, you realize that nearly everything in the world humans have made for themselves is engineered. “I often start off my introductory course by asking my students about an interesting example of engineering they’ve encountered. And often, they can’t think of anything. But with just a little prompting, soon they’re realizing that their phones, the roof over their heads—all of these are things that someone had to design and engineer.”

Forléo’s favorite example is something he discovered inside a Honda Civic, sometime in the 1990s. In the mechanism of a modest storage drawer in the car’s front console, a single ball bearing slides back and forth with the vehicle’s acceleration, ensuring the compartment stays shut when the Civic is moving, but allowing it to be easily opened with a gentle pull.

While his students may have not the slightest idea what a Honda Civic from the 1990s even looks like, the message still resonates: Engineering often means finding surprisingly elegant solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems.

“It is easy to take the things around us for granted,” Forléo says. “But not doing so—being the one brave enough to break things, to tackle the complexities of making life better—and failing over and over again along that journey: This is the real value in CA’s Engineering Design program.”