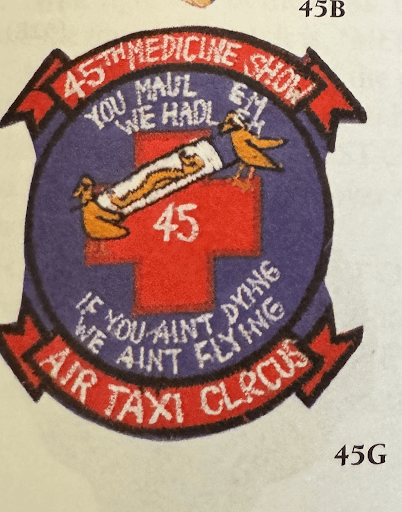

This week in my Vietnam War history class, Paul Harpole, the grandfather of four Colorado Academy students, came to share his experience as a “Dust Off” Crew Chief in Vietnam. After being told by his teachers that he wasn’t “college material,” Paul joined the Army at age 17. The recruiter mistakenly told Harpole he could not fly as a crew member or pilot because he wore glasses. After joining, that proved to be incorrect, and he found himself trained as a helicopter crew chief. During his training, he learned to fire an M-60 machine gun from a Huey helicopter. When he got to Vietnam after his 18th birthday, he was dropped off at the 45th Medical Company. He noticed that none of the helicopters had guns and thought they were being serviced. And then he learned he was part of the Dust Off unit, and these helicopters carried no guns.

Known for its call sign, a Dust Off crew, consisting of two pilots, a medic, and a crew chief, provided medical evacuation to the wounded and dead. During the war, Dust Off missions evacuated more than 950,000 people—Americans, Vietnamese civilians, Viet Cong, and NVA soldiers. Service in a Dust Off unit was completely voluntary—a soldier could walk away from the unit at any time because their missions were so dangerous.

Speaking to my students for more than an hour, Harpole gave a riveting account of his experiences in Vietnam from 1969 to 1971. He talked at length about the technical realities and harrowing nature of serving in a Dust Off helicopter.

A critical part of his job was to maintain the “ship.” He also managed a hoist, which could raise a load over 200 feet from the ground. Dust Off crews would fly repeatedly into danger to retrieve patients. (He always referred to those whom they evacuated as patients, which reveals his tremendous compassion.)

Often the pilots would have to maneuver through a triple-canopy jungle, while under fire, to rescue soldiers. At one point, he showed a photo taken on one of his missions. At first, it just looked like a shot of the jungle. Then Harpole asked if we could see 10 faces. As we all strained our eyes, faces emerged from the jungle. These were soldiers looking up while Harpole lowered the hoist to pick up a soldier. As soon as the patients were on board, the pilot flew out as quickly as possible to a medical unit.

In an emotional moment, Harpole described his first mission on September 5, 1969. He hoisted up a blond, blue-eyed soldier who had been killed by a booby trap that had just eviscerated his body. He described another mission in which an American unit got caught in an L-shaped ambush. There were 13 KIA (killed in action) and 25 wounded. They flew repeated missions to pull the soldiers out. One day they flew continually for 25 hours. Although the helicopter was designed to carry nine patients, they often put more on the ship. One time, they carried out 21 KIA and wounded. After a long day of pulling soldiers out, he realized it was his birthday. He talked about receiving a medal for his service—and showed a photo of it being pinned on his uniform—but the Army did not record his commendation for valor. As he described this to the students, he demonstrated his incredible humility. He said he was just doing his job—it wasn’t about being a hero.

Harpole described several close calls. He survived five crashes. Of these, three were times when they were shot down, and two were mechanical failures. One of these included a time in which they were flying 12 civilians out of Cambodia. They crashed into a rice paddy. Paul carried the only weapon—an M-16 with a handful of ammunition clips. It was pitch black and he was buried in muck guarding the crew and civilians. A group of militia approached, and fortunately for them all, it was a militia aligned with the Americans.

He showed photos of when their ship was hit 18 times by small-arms fire that wounded the two pilots, and he felt shrapnel. On one mission, they were flying low, and Harpole spotted an NVA soldier lifting his rifle to shoot at the Huey. He yelled to the pilot, who quickly turned the helicopter, but not before the NVA soldier got off a shot that pierced the side of the ship. It was one of many close calls that Harpole experienced.

Aside from modeling humility and courage, Harpole shared some great advice. He told the students, “Don’t you dare ignore your mentors.” He described an interaction with a medic who changed his life. One day, they were talking about what they were going to do when they got home. The medic encouraged Harpole to go to college. When Paul told him he had always been told he wasn’t college material, the medic said, “You have the ability to focus more than anyone I know.” Paul did go to college, became the owner of auto dealerships, and eventually served as the Mayor of Amarillo, Texas.

He noted that while he never cried while in Vietnam, he does get emotional now, and told the students he would not apologize for it. We got emotional as he described one of his final missions. Harpole carried two children with multiple amputations to an orphanage. When they arrived, a nun carrying these children and put them in his arms. The orphanage was dedicated to children who were all amputees. To our students, Harpole said, “We can’t count how lucky we are. Don’t think you’ve got it bad. Take advantage of everything you have.”

When I asked him what he learned about himself in Vietnam, he said, “I learned I could do anything.” Harpole did a lot; he and his crews saved thousands of lives. He estimates that he personally took part in the evacuation of 4,500 people.

Thank you, Mr. Harpole, for your service and wisdom. The message that resonated with me most was how he modeled courage then and now and how he consistently overcame significant obstacles throughout his life. Mr. Harpole’s ability and confidence to communicate this story and show a range of genuine emotions showed true courage, and I can’t thank him enough for spending time with us.