Author and Colorado Academy English teacher Emily Pérez’s two most recently published works are finalists for the Colorado Book Awards, which annually celebrate the accomplishments of the state’s outstanding writers, editors, illustrators, and photographers.

That both books—What Flies Want, a collection of original poems, and The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood, an anthology of other writers’ poems and essays that she co-edited with Nancy Reddy—also have in common their shared concerns with gender roles, race, parenting, and family comes as no surprise.

Growing up as the child of a Mexican American father and white mother in a rural Texas border town where such mixed marriages were rare, Pérez says, she found herself constantly wondering about her place in between cultures and identities. In a region that was almost entirely Mexican and Mexican American, she explains, “I was always negotiating questions of, ‘Where do I fit?’ and ‘Where do I not?’”

Pérez also had to reconcile the idea that her mother, a feminist, had married into a rigid, patriarchal culture. “I had to make sense of what it means to believe that women are equal to men, yet for a woman to take on all these roles in which she is not.”

All the while, Pérez was growing into a complicated sense of her racial and ethnic identity. “Even though my siblings and I were very white-presenting, everyone in our small town knew our family and accepted us as Mexican American, just like our neighbors,” she says. “But once we left home, we realized outsiders saw us simply as white. That set off a lot of questioning inside of me about who I am—do I need to always assert who I am in order to be that person, and how do I live in this world?”

“Ask me on any given day or year,” Pérez observes, “and my answers to all these questions will probably be different.”

Myriad though they may be, those answers, and the questions that inspired them, have offered fertile terrain for Pérez’s work as a poet, essayist, and editor.

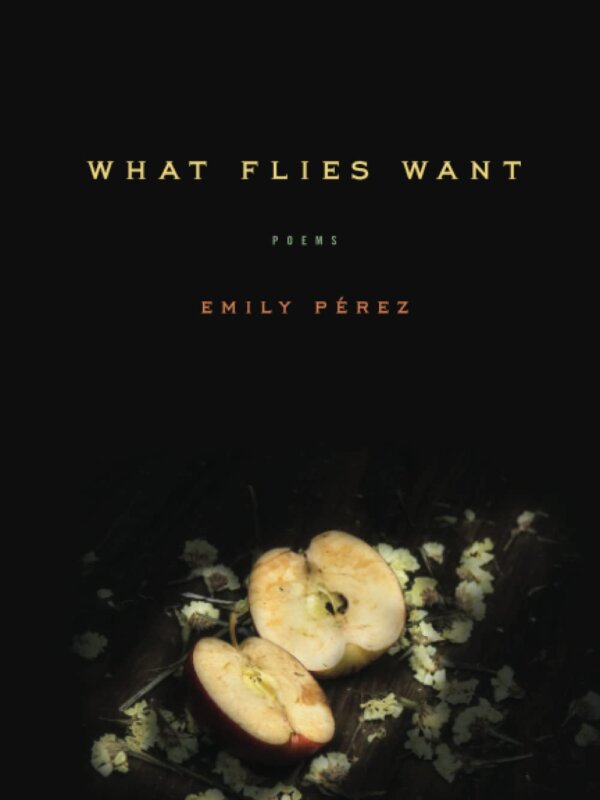

In her first full-length collection of poems, House of Sugar, House of Stone, she explored the fear and anxiety inherent in becoming a parent, wondering whether raising children is at all compatible with art and creativity. In 2022’s What Flies Want, already the winner of the prestigious Iowa Poetry Prize, Pérez reflects on her position as the mother of two white boys coming of age in a culture where guns and racism loom large. Marriage and mental health issues, the #MeToo movement, and the rise of gun violence in schools provide the backdrop for her tense interrogations and hard-won moments of joy.

“My children use the American flag / pole / as a bayonet,” she writes. “I have not taught them / ‘patriot’ or ‘desecrate’ / or ‘swords / into ploughshares.’”

“In this book,” she says, “I’m really asking, ‘As a parent, what’s my role in all this?’” The poems first began to take shape as her young children were becoming interested in playing with toy guns and simulating violence, and Pérez started wondering how they were learning about these things, and what she would permit or prohibit. “That grew into thinking about what I learned about violence when I was their age, and how messages about guns and violence were gendered.”

The notion of whiteness also found its way into the poems in What Flies Want, as Pérez saw how it played a role in her own upbringing.

“I don’t know if I could have articulated it at the time, but it’s startling now to notice how my family and my community valued whiteness,” she recounts. “White people were very much in the minority, yet whiteness was what we aspired to. In elementary school, I was educated by Latino or Latina teachers, but we never learned anything about our culture.”

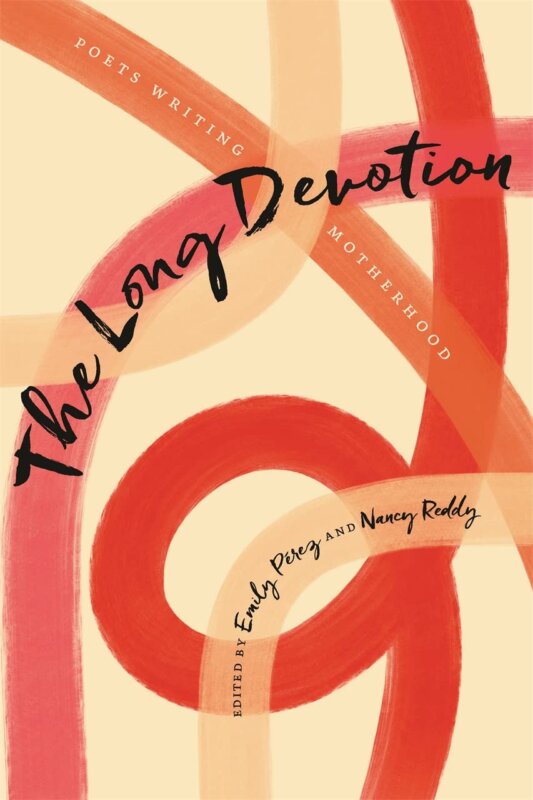

Dark as the poems in her poetry collection sometimes are, Pérez with her co-editor Reddy wanted to capture the complete spectrum from dark to light in The Long Devotion, which recognizes the vast range of exciting work about motherhood that has emerged over the past two decades.

“We set out with this book to update the existing landscape of anthologies about motherhood,” she says.

It used to be, she explains, that people writing poetry about topics such as pregnancy, miscarriage, or parenting through illness were confined to publishing in less than a handful of explicitly feminist journals. But today, Pérez says, literary outlets across the spectrum are highlighting new work about everything from IVF (in-vitro fertilization) to adoption and the choice to remain childless.

“Motherhood is finally a thing that is not considered a niche or taboo subject,” she says. “We wanted to showcase how the literature on motherhood has really exploded in a positive way, exploring so much more than ever before.”

With writing prompts to accompany the poetry and essays, the anthology has proven accessible to a wide range of readers. “We’ve seen that people all along the caretaking spectrum—who are not necessarily writers—are using the prompts as guidelines or models to capture and express something that maybe they’re experiencing in their lives.”

Modeling the creative process is one way that Pérez brings the insights from her writing life into her classroom at CA. Teaching poetry, fiction writing, and narrative nonfiction, she emphasizes risk taking, playing with form and structure, as a way to honor the self reflection and constant process of refinement that are central to all great works.

“With my Ninth Graders, we spend more time learning about structure and the patterns that they need to master as a writer. But by Eleventh and Twelfth Grade, I’m asking them the questions, ‘Now that you’ve learned these patterns, what can you do to subvert them? How can you take a risk and do something more interesting?’”

Pérez reminds her students that with risk and experimentation comes the need to revisit, ask for feedback, and revise. She uses a recent experience producing a lengthy literary review as an example.

When she handed in a 10-page draft of the essay, her editor quickly cut the first page and a half—a devastating edit, but one which ultimately made the piece much better. Pérez shows her students the Word document with that enormous change tracked—strikethroughs, margin notes, and all—and the message is crystal clear.

“I’ve been writing for most of my life—more than twice the years they’ve been alive—and even I still get feedback like this, because there are still things for me to learn about being a writer.”

And that’s a good thing, Pérez insists.

“Poetry lets me keep coming back to a whole piece and working on it and revising it, even though, as a parent and a teacher, I don’t have large blocks of time to dedicate to it. At the same time, poetry is such an expansive genre. Today it’s even merging into visual work—poetry comics, poetry films. The genre can just encompass so much, and that’s always been really exciting to me. I love sound and I love music, and poetry has been the place where you can say so many things with those, as well as through white space and implication.”

“You can do that in other forms of writing, too,” acknowledges Pérez. “But I think in poetry, you can do more of what Robert Bly calls ‘leaping’—from the conscious to the unconscious, from the concrete to the metaphorical—and know that the reader will go along with you.”

For Pérez the teacher, the exciting part is not that her students “go along,” but that they are constantly pushing forward. When she asks them to share the concerns that inform their work, she is inspired to note that they are usually not the same ones that drive her own.

Where her “writing obsessions”—motherhood, race, family, violence—mostly remain within the confines of her poet’s “secret life,” in her CA classroom, thoughts about the environment, love, and gender identity often come to the fore.

“In so many ways, my students are ahead of most adults in their understanding of these things. They’re hungry for literature that reflects the world that they live in, and they’re impatient for us to catch up.”