“What can we, as Colorado Academy students, do to assist in situations where someone is being treated unjustly? How can we get involved in the global fight for justice?”

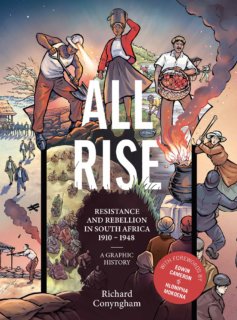

Those questions, asked by a Ninth Grader participating in a virtual Q&A with the South African author and historian Richard Conyngham, spoke eloquently to the themes in Conyngham’s debut graphic collection, All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa.

Ninth Graders had read the book over the summer, and at the start of the fall trimester were discussing it in their foundational Global Perspectives course, which equips them with historical inquiry skills necessary for global citizenship and understanding the historical roots of modern conflicts.

The course begins with the history of human rights, moving from Enlightenment thinking to the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as students look at case studies showing how governments and people interact when rights conflict.

“Through a thematic exploration of human rights, globalization, and the environment,” says Upper School history teacher Randall Martínez, “Global Perspectives teaches students to engage in collaborative dialogue and to research ways to promote peace on micro and macro levels for a sustainable future.”

“Most classes that deal with apartheid only begin their studies during the apartheid era,” Martínez points out. “What Conyngham’s novel is able to demonstrate for students is that the erosion of rights is a long and slow process where the groundwork of division is spread out over time to make oppression more likely.”

A pivotal time in South African history

Richard Conyngham via Zoom.

The Q&A with Conyngham, hosted by Martínez via Zoom on September 14, 2022, gave students a chance to dig deeply into the author’s work, an anthology celebrating six pivotal human rights court cases—the stories of which have never been told before—in South Africa’s pre-apartheid years. Conyngham and his book’s illustrators—the stories are envisioned by seven different South African artists—depict the struggles of ordinary women and men who defended the disempowered during the tumultuous period of colonial rule from 1910 to 1948.

It is a period few South Africans know anything about, explained Conyngham.

“When most people, including South Africans, think of our country,” he said, “they think of apartheid, the period between 1948 and 1994, which has totally dominated our history ever since South Africa became a democracy. Go into the history section of a bookstore in South Africa, and the majority of the volumes will be about apartheid—mostly its icons, like Mandela, or its villains. These were extraordinary people, but the time in which they lived, as significant as it was, was not the only significant era in South African history.”

The span between 1920 and 1948, known as the Union Years, provided the foundation upon which apartheid was built. “It tells us why apartheid happened, and it tells us why South Africa is the way it is today. This is why I chose to tell the stories I did.”

Years in the making

Conyngham spent seven years working on All Rise, much of the time devoted to researching stories of resistance that were all but buried in the dusty archives of what once was South Africa’s highest court, in the capital city of Bloemfontein.

“I knew there were extraordinary people during this time period whose stories deserved to be heard, and there they were, in those archives,” Conyngham told the students. “Understand, they were not necessarily exceptional people. They were everyday people, they were working-class people of different races who lived in different parts of the country, and they had made the brave decision to resist what they believed was an unjust law. As a result, they broke the law, they ended up being arrested, and they ended up going to court. From that point forward their names were recorded in history forever.”

In some cases, the court archives provided a plethora of details to help Conyngham frame the story of each individual, ranging from immigrants and miners to tram workers and washerwomen. Where documentation was sparse, the author relied on the power of art to fill in the gaps, and each of the illustrators Conyngham worked with endeavored to capture the stories of the unsung heroes in their own way.

His decision to collaborate with multiple artists reflects the unique character of South Africa itself.

“Most books like this one,” he explained, “are created by a lone author/illustrator, or by a writer who works with a single artist. So the decision to work with seven illustrators was unorthodox. But looking back on it now, I’m very glad that I chose this route. The different creators were able to bring to the book so much more than one person could ever have accomplished. More importantly, it speaks to the diversity of my country.”

“South Africa is a place with this uncomfortable mix of different cultures, different identities. It is what makes our history so fascinating, and it is part and parcel of why South Africa is so beautiful.”

The power to make a difference

Responding to the question from a student about fighting injustice, Conyngham reflected on his own experience as an author.

“We are living in a time with huge prevailing issues,” he admitted, “and your generation—you, the students—are the ones who must embrace this challenge more than anyone. But how? There may be among you those who will become lawyers or activists later in life, who will use the law to combat injustice. But that is not for everyone.”

“I know that I am not brave enough to be an activist on the front lines,” Conyngham continued, “or smart enough to be a lawyer in court. But I am a storyteller. There are stories all around us—stories shape our world, and they also shape the way we see the world. If you have the instinct of a storyteller in you, go out and tell stories. You don’t have to be a Mandela, you don’t have to be a Gandhi to make a difference. It’s about using your strengths and believing in your own power to make a difference. That is how to change the world.”