I have written and spoken before about how I was raised with split personality when it came to politics. I had one grandfather, a lifelong public servant, who gave me a subscription to the Washington Post Weekly. Then, my other grandfather, who managed a number of coal mines, learned about this gift and got me a subscription to the National Review to make sure I didn’t turn into a “communist” (his words). So, throughout high school and college, I read opposing views of current events every week.

My senior year in high school, I took a current events class with a brilliant teacher named Howard Zeskind. Zeskind made us to argue for positions we did not agree with, just to expand our perspective and help us hone our argumentation skills. My grandfathers probably wouldn’t agree on many things, but they were both on the same page of how important it was to gain an education, and, in particular, an education that challenged one’s assumptions about the world. Both contributed to my education in meaningful ways, and for that I am eternally grateful.

We talk a lot about how we teach critical thinking at Colorado Academy. When you walk through our classrooms, teachers are constantly asking students about what they think and why. Despite all the technological innovations that have improved teaching and learning, helping students learn to develop critical thinking abilities comes down to age-old practices. Thank you, Socrates!

We can’t understand ourselves without first asking hard questions. Right now, I have been fixated by the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. The New York Times published an interesting article about how communist officials have been worried about a civics class in Hong Kong that they believe has contributed to the unrest. The article notes the tensions between promoting a sense of nationalism, while also being accurate about the failings of the regime.

To be sure, the United States has wrestled with how we address the sins of the past and the darker angles of our history. In some states, there have been tough debates about curriculum and how civics is taught. I think looking at a different nation’s experience, like that of China and Hong Kong, can help remind us of the virtue of knowing our past—the good, the bad, and the ugly. The key is helping students understand how to move forward as informed people who understand context, perspective, bias, and interpretation.

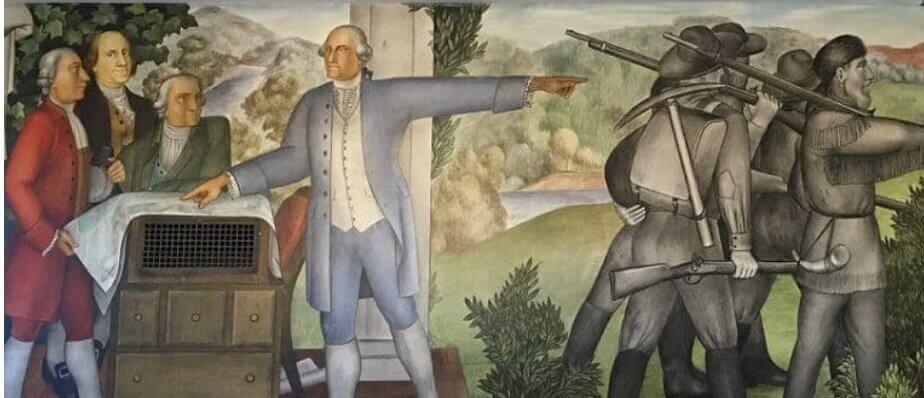

I was struck this summer by a decision of the San Francisco School Board to destroy a mural of the life of George Washington because it addressed the issue of slavery and the subjugation of Native Americans.****

You may have heard this story already…

As part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Russian émigré and artist Victor Arnautoff painted the murals in a San Francisco high school. The feeling of the School Board was that the murals were offensive to current students, particularly students from diverse backgrounds. One panel depicted a dead Native American, and others depicted slavery. However, as many scholars have noted, the work might be “among the honest and possibly most subversive of the WPA era.” The artist in question was a communist and protégé of Diego Rivera. His Washington was not the typical patriotic approach one might find in the 1930s.

Of course, the irony of the liberal-leaning San Francisco School Board censoring a communist’s work of art would have made my conservative grandfather wheeze with laughter. The alumni organization of the high school argued to keep the mural: “This is a radical and critical work of art…. Arnautoff murals should be preserved for their artistic, historical and educational value. Whitewashing them will simply result in another ‘whitewash’ of the full truth about American history.”

What is most interesting to me is that many students at this school do not want the murals to be destroyed; in one writing assignment, only four of 53 students supported getting rid of it. Most young people understand the danger of censorship. And, we can see that play out now in the streets of Hong Kong.

I remember one of my professors from Vanderbilt, the great Paul Conklin, giving a talk on Lyndon Baines Johnson. Conklin wrote a great book on LBJ called Big Daddy from the Pedernales. LBJ, like so many other leaders, had many flaws. While he wanted to fight a war on poverty, he also fought a real war that was problematic on a host of levels. After his talk, a person in the audience asked Conklin, “How would history judge LBJ?” Conklin took a moment and said, “History doesn’t judge. Historians do.” Everything humans perceive and argue is shaped by bias at some level. Making sure our students understand bias, perspective, and common sense can only help make us a better nation and our students better people.

****For historians who have studied George Washington, we know he was a highly complex thinker and changed his view of slavery over the course of his life. Perhaps like no other Founding Father from a southern state, he saw and felt the contradiction inherent in the American Revolution—a nation that called for individual freedom while it still enslaved human beings. However, he was not an abolitionist and held prejudiced views that we would not agree with today. His will called for the slaves at Mt. Vernon to be released upon Martha’s death. The story is far more nuanced than most realize, and I applaud how the Mt. Vernon website has tried to educate Americans on this sensitive part of our nation’s history.